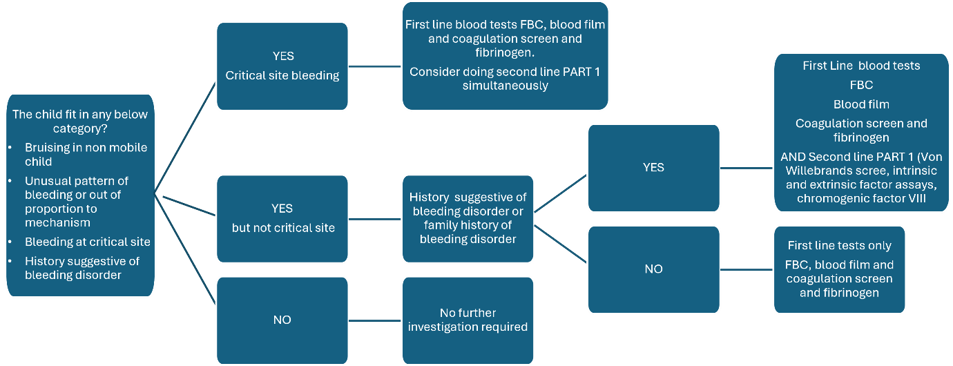

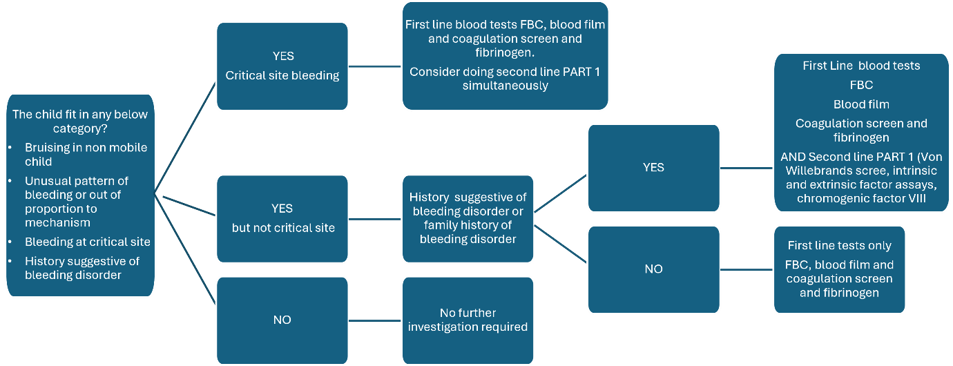

Children fitting into one of the categories in Box 2 should be considered for First line Investigations (Box 3). Second line investigations are divided in part one and part two investigations (Box 4). See the flow chart below to help guide whether to do second line part one investigation simultaneously with first line investigations.

Second line part two investigations should only be done after discussion with paediatric haematology. This can be with the registrar who would be expected to discuss all child protection cases with the on-call consultant. In cases of high suspicion of a bleeding disorder, it may be appropriate to do all second line tests simultaneously with first line tests after discussion with a haematologist, to avoid multiple sampling attempts. Dect phone at RHC is 85645 for the non-malignant haematology registrar.

Second line tests often have additional sampling requirements (specific bottles/day test is run etc) so need careful planning so as not to unnecessarily bleed a child repeatedly and waste laboratory resources. Repeated sampling due to inappropriately ordered and handled tests can cause unnecessary pain and stress for the child and their family.

Please see next section for important information around logistics around ordering and handling samples for second line tests. Several of the tests have similar names so it is important the correct test is ordered for the correct patient.

Box 3: First line investigations:

- Full blood count

- Blood film

- Coagulation screen INCLUDING fibrinogen

Box 4: Second line investigations:

PART ONE

- Von Willebrand screen (antigen and activity)

- Factor assays (intrinsic and extrinsic pathways)

Including 1 stage and chromogenic FVIII, FIX

PART TWO (following discussion with haematology)

- FXIII

- Platelet membrane glycoproteins

- Platelet nucleotides

- (Platelet function tests)

Chart 1: Pathway to guide haematological investigations

|

Critical Sites

Intracranial

Retinal

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Intraspinal

Haemoarthrosis (joint)

|

If clinically you feel this child may have a bleeding disorder, please discuss with the non- malignant haematology team for further advice.