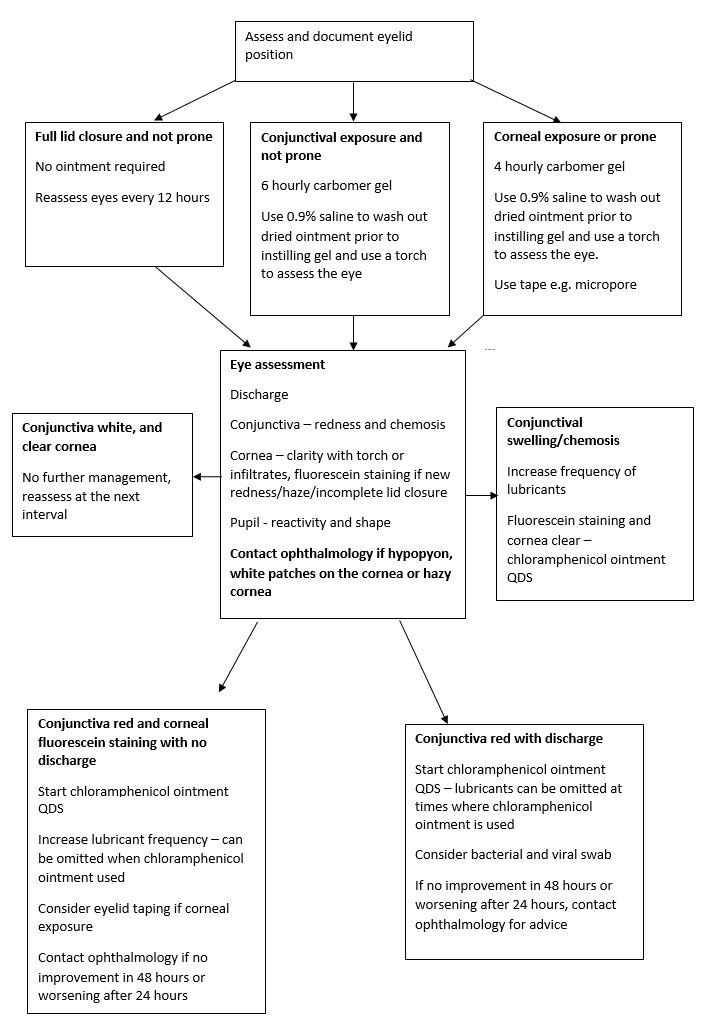

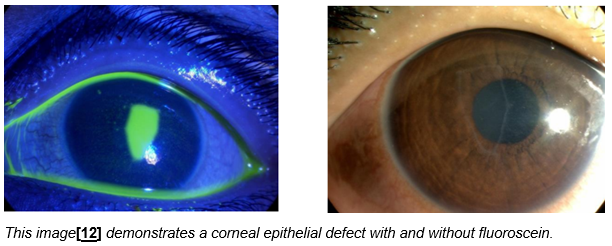

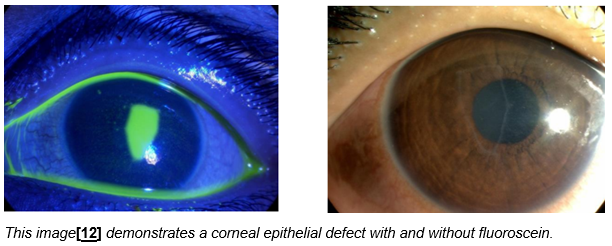

Exposure keratopathy

This is a corneal epithelial defect which occurs in those with incomplete lid closure. It is best seen with fluorescein eye drops and a blue light preferably, but may also be visible with a white light.

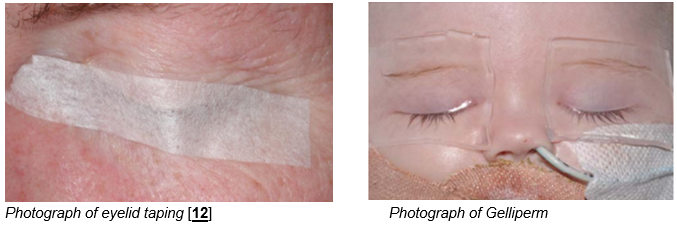

In the first instance, use chloramphenicol ointment 4 times a day, increase the frequency of lubricants and consider lid taping.

Contact ophthalmology if:

- The cornea is not clear with a bright light

- White patches are present on the cornea

- The epithelial defect covers more than one third of the cornea

- There is no improvement within 48 hours after increasing management

If there is a corneal abrasion with full lid closure, chloramphenicol 4 times a day for 5-7 days can be used.

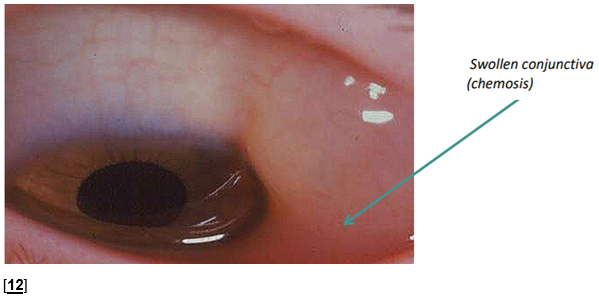

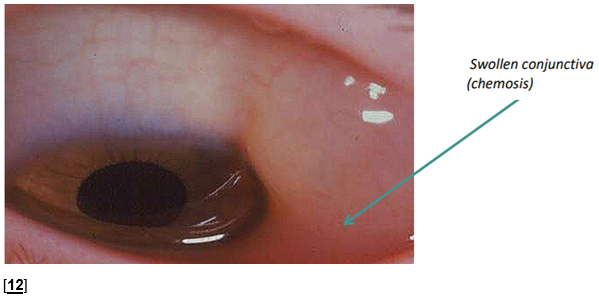

Chemosis

Conjunctival chemosis, causing swelling and bulging of the conjunctiva, is common in patients who are ventilated, particularly with positive pressure ventilation, patients with generalised oedema or those that are prone.

Chemosis can lead to poor lid closure leading to exposure of the cornea and infection. These patients can often be managed with increased lubrication and taping however refer to ophthalmology if:

- The cornea is not clear with a bright light

- White patches are present on the cornea

- The epithelial defect covers more than one third of the cornea

- There is no improvement within 48 hours after increasing management

Microbial Infections

Respiratory secretions may be a common source of bacteria in those in PICU, so care should be given when suctioning is being performed. This should be done from the side rather than at the head, and the eyes should be covered.

Conjunctivitis

This is an infection of the conjunctiva. The eye is usually sticky with debris on the lashes and a red eye. If the eye is red without stickiness other causes should be considered. Discuss with ophthalmology if the cornea is not clear.

Conjunctivitis may be bacterial or viral. Use chloramphenicol ointment 4 times a day for 7 days and send a viral and bacterial swab. If the swab shows sensitivities to other antibiotics but there is a clinical improvement, continue chloramphenicol.

Microbial keratitis

This is an infection of the cornea. Patients with exposure keratopathy are more vulnerable to this due to loss of the protective epithelial barrier. A white patch may be visible on the cornea which usually stains with fluorescein, the cornea may be hazy with a bright torch and the eye will turn red. These patients should be referred to ophthalmology.

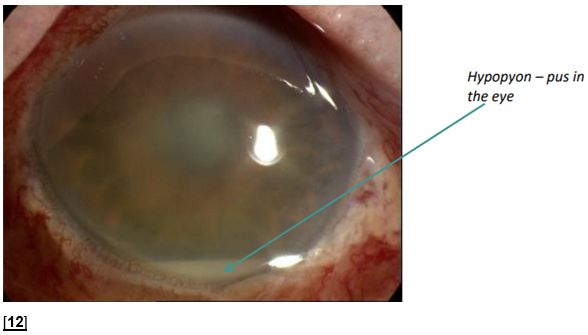

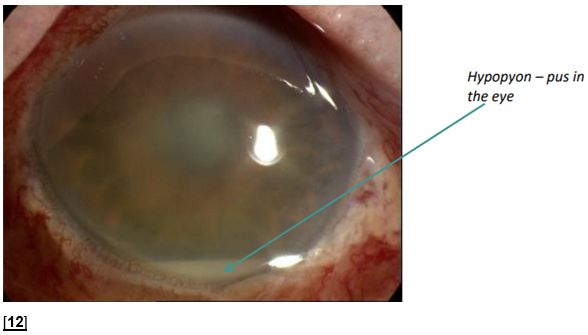

Endogenous endophthalmitis

This is a serious and rare complication of a systemic infection. The eye may be red with poor visibility of the pupil and iris with a bright torch. It should be suspected in those with a white line of pus called a hypopyon and requires an urgent ophthalmology review. It indicates active sepsis and requires systemic treatment.

Chemical eye injury

- 1 litre of saline irrigation

- pH strip – test conjunctiva to ensure pH is 7-8, if not continue irrigation until pH normalises

- Fluoroscein – if there is fluoroscein staining use chloramphenicol ointment 4 tmes a day for 5 days

- Contact ophthalmology for advice if the substance is significantly acidic or alkali