Pregnancy testing guidelines for girls aged 12 yrs & over (RHC)

Objectives

Provision of a guideline and flowchart for pregnancy testing in children

Scope

For girls aged 12 yrs & over

Audience

Medical and nursing staff caring for girls aged twelve years and over

The National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) all state that pregnancy status should be ascertained in females of child-bearing age prior to operations and certain investigations which could be harmful to fetal and maternal health 1,2,3.

The RCPCH further recommend that organisations have a clear, locally agreed and audited procedure for ensuring documented compliance in this area, including specifically for females under the age of 16 years3. This was set out in the RCPCH 2012 guideline ‘Pre-procedure pregnancy checking for under 16s – guidance for clinicians’.

Pregnancy testing may also be indicated by the clinical presentation of the patient, such as in acute abdominal pain.

Fertility in young women has an uncertain starting point, and the onset of periods is not a reliable indicator of fertility. The implication of sexual activity in under-16s will be a sensitive subject for the young person and their parents/carers, and also carries child protection concerns. There is evidence that under-16s may feel unable to respond accurately to questioning about their sexual activity and risk of pregnancy5. For these reasons, pregnancy testing rather than verbal questioning alone is the most reliable way of determining pregnancy status in these patients.

It is recognised that racial, cultural and ethnic factors may require additional sensitivity. For patients with known specific vulnerabilities, assessment must be especially thorough. For patients with communication disabilities, every attempt must be made to overcome these difficulties.

Pregnancy testing in patients under-16 has the potential to uncover child sexual abuse and child exploitation. A positive pregnancy test or admission of sexual activity in patients under 16 will require a safeguarding assessment and response.

Girls aged 12 or over who are:

- Scheduled for surgical or medical procedures

- Admitted with acute abdominal pain

- Investigated involving ionising radiation

- Receiving teratogenic medication including chemotherapy

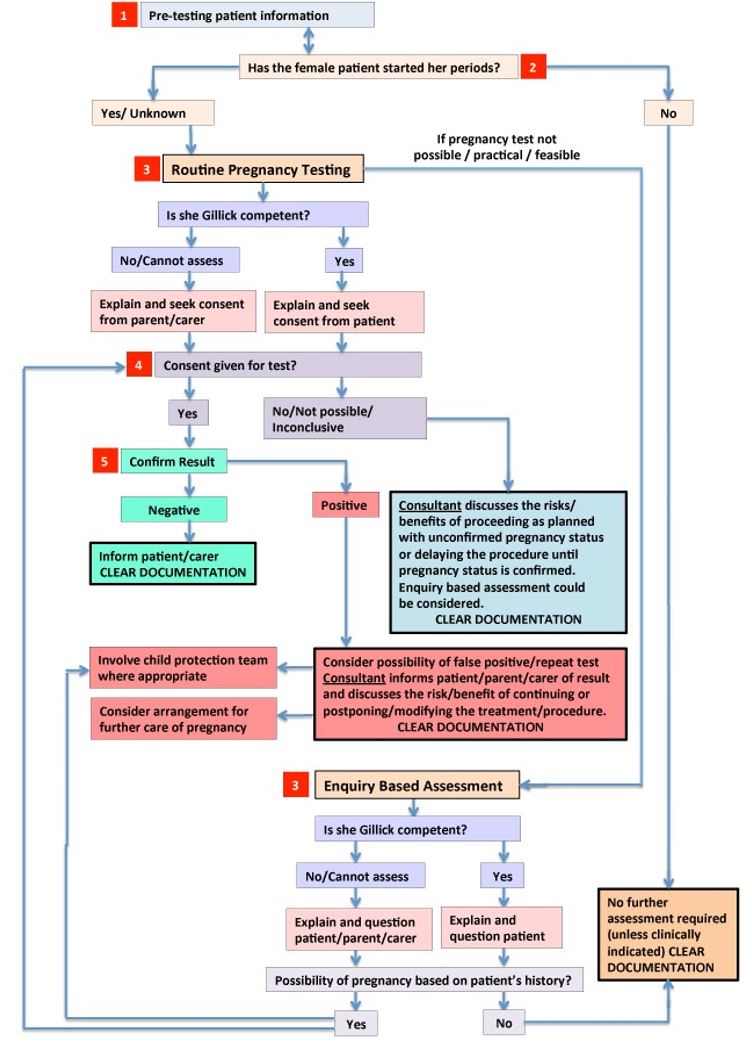

The following flowchart was adapted and reproduced with the permission of the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital. It aims to promote a consistent approach for practitioners assessing pregnancy status in patients at RHC prior to risk-associated procedures.

*Chart at RHC modified for Scottish law.

See below for more information regarding each numbered flowchart step

1. Pre-testing patient information (see also Patient Information Leaflet)

If possible patients should be informed at the earliest opportunity. The testing should be part of a routine assessment process, and this should be explained to the patient and parents/carers where appropriate. This will aid greatly in reducing elements of embarrassment and sensitivity during subsequent discussions on admission.

Pre-operative pregnancy testing should ideally be discussed at the surgical or pre-op assessment clinic and information given about the reasons for testing, including the Patient Information Leaflet.

The pregnancy test itself must be carried out on the day of the procedure.

For unplanned admissions, the same level of information and discussion should take place as far as possible, as soon as the responsible clinical team identifies the need for pregnancy testing.

Female patients deemed to be competent to consent have the right to have all discussions in a sensitive, confidential manner separately from their parents/carers. Any information disclosed should be used in confidence unless there are overriding safeguarding considerations.

It is sometimes difficult to contrive a way to separate patients from their parents to ask sensitive questions, but it might be enough to suggest that as the patient is nearly an adult, there are a couple of questions they may like to answer by themselves in private. The parents may then be asked to leave the room, or the patient given the opportunity to move to a private space with the healthcare professional. Given the responsibility that parents have for the conduct and welfare of their children, professionals should encourage the patient, at all points, to share information with their parents and carers whenever safe to do so.

2. Has the female started her periods?

A wide variance in the onset of menarche is reported. However, data suggest the likelihood of pregnancy in those under 13 years presenting in the hospital is negligible. As a consensus the age limit has been agreed to 12 years and over unless clinically indicated otherwise.

Radiology will require confirmation of last menstrual period regardless. The referrer may overrule this process, but accepts responsibility for the decision if it transpires that the patient is pregnant.

3. Routine Pregnancy Testing versus Enquiry Based Assessment

There are two possible options for ascertaining pregnancy status in female patients – consented pregnancy testing or direct enquiry. The testing should be considered as first line approach. In cases when this is not possible, practical or feasible, enquiry based assessment should be performed and documented.

In some cases the clinician caring for the patient may consider the possibility of pregnancy to be so remote that neither enquiry nor testing are necessary. This decision should however be documented.

Patients should be questioned sensitively about whether they have started their periods. The start date of their last period should be recorded and they should be asked if there is any possibility they could be pregnant, qualifying this by asking if they are sexually active in a way that could result in pregnancy. They might also be asked at this stage whether they are taking oral contraceptive medication or using other contraceptive methods.

If the patient reveals a possibility of pregnancy, as yet undetected or undisclosed, she should be consented for testing. In the cases when consent is denied, the responsible clinical team must discuss further actions. Safeguarding implications may apply.

4. Consent

Covert pregnancy testing may be seen as an infringement of human rights and must not occur.

Clearly documented verbal consent should be obtained from the patient, or parent/carer if the child is not considered competent to consent. Clear explanation might be necessary and sensitive handling of the discussion is required particularly where the age of the patient or indications of cultural sensitivity around premarital or under-age sexual activity are considerations. It is essential to have a professional interpreter or independent advocate if this helps the patient or family to make decisions. The GMC guidance on personal beliefs and medical practice provides further information5.

For some procedures, e.g. emergencies, the patient may not be competent to give consent. Parental consent to perform a pregnancy test on a minor lacking capacity in an emergency situation is not required provided the treatment is immediately necessary to save the patient’s life or to prevent a serious deterioration of the patient’s or unborn fetus’ condition.

The legal framework on consent and confidentiality with particular relevance to children and young people is covered by the GMC publication ‘0-18 years: guidance for all doctors’6.

In cases where consent is denied, the clinical team must explain the risks of proceeding. Effort should be made to quantify the risk so that the patient/parent can make an informed decision. In situations where the risk of an undetected fetus would be considered unacceptable, the lead clinician is justified in refusing to undertake the procedure/treatment/investigation.

The ultimate responsibility for these discussions & documentation is with the senior clinical lead in the team.

5. Results

All results must be documented in the notes.

Four possible readings could be obtained following ward-based urine pregnancy testing:

1. Negative – the patient (or her parent/carer, if the she is not competent) must be informed of the result in a confidential manner.

2. Borderline – must be followed by a laboratory blood βhCG test.

3. Invalid – must be repeated and if the test fails again a laboratory blood βhCG test must be carried out.

4. Positive – a laboratory blood βhCG test to confirm pregnancy should be organised.

If the result is positive, the lead clinician should be informed immediately and should meet with the patient, with the support of her named nurse, to discuss the result and the implications for the proposed procedure/treatment/investigation. With the permission of the competent patient, and for the patients not considered competent, parents/carers may be asked to join these discussions.

The clinical team caring for the patient must also make a judgement about the need to involve the safeguarding team in the patient’s on going care and make sure that appropriate advice is given regarding pregnancy management.

False positive readings can occur in various cases of:

- Failed implantation (early miscarriage)

- Choriocarcinomas, gestational trophoblastic diseases and neoplasms

- Other malignancies

- Excess bacteria present in the urine (e.g. bladder or kidney diseases).

False negative readings can occur with:

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Sample of urine is too dilute

- When testing is done too early in the pregnancy

- Where very high concentration of βhCG level can cause saturation of the antibodies leading to a negative results (the Hook effect)

However, these are very rare occurrences.

Patient information leaflet (pdf): Pregnancy testing - why am I being asked?

- Use: Alere hCG cassette - 25mlU/ml, ref: CV506788B

- Any equivocal or ambiguous results: send a lithium heparin or serum sample for βhCG.

The pregnancy testing cassette detects presence of urine β human chorionic gonadotropic hormone (urine βhCG) within a few days of implantation of an embryo. Early morning specimens of urine have the highest concentration of urine βhCG and therefore are more accurate.

Prior to urine βhCG analysis, the sample must undergo standard urinalysis. If there is haematuria or a low specific gravity, the sample is not suitable for urine βhCG analysis.

The average turnaround time for blood βhCG testing is 60 minutes from the time the sample is received in laboratory. If required urgently contact the biochemistry laboratory directly.

Pregnancy status should ideally be ascertained within hours of a planned procedure/investigation/treatment.

The responsibility for ascertaining pregnancy status on the day of the procedure will remain with the clinical team. The registered nurse admitting the patient to the ward can carry out the testing/questioning providing verbal consent is gained. This should be done early in the admission process to avoid delays.

The patient pregnancy status should be known prior to the start of an operating list and form an essential part of the pre-operative documentation. Clear documentation will also avoid the need for further sensitive discussions in the anaesthetic room, where parents may be present.

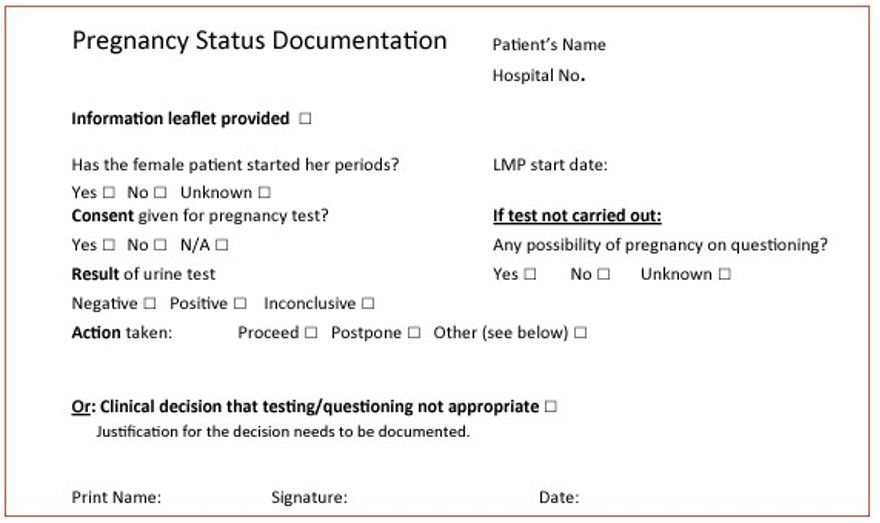

Clear documentation of the following:

- Consent (or refusal of consent) to pregnancy testing

- Pregnancy test results and action taken

- Any relevant decision made by the lead clinician (e.g. if pregnancy testing not necessary/appropriate) should be recorded in the peri-operative surgical pathway, or in the patient notes

- For a positive result, there should be extensive documentation in the medical notes of the clinical and safeguarding actions taken in the light of the result.

RCPCH suggested minimum documentation:

The process of ascertaining pregnancy status may reveal sexual activity in female patients, which needs consideration from a safeguarding point of view even with a negative pregnancy test.

Patients under the age of 13 are considered by law in the UK as unable to consent to sexual intercourse and it is considered rape. In all cases of positive test result or disclosure of sexual activity in this age group, a referral must be made to the tier 3 safeguarding consultant on-call (contact via switchboard), police & social services. The responsibility to do this rests with the clinical team. The patient should be told that this information is being shared in her best interest.

The patients aged between 13-15 are below the age of consent. Further history should be taken from the patient. This should be enquired about sensitively and in private. Any disclosure of coercion, sexual activity with a partner aged over 18 or indications of abuse should prompt discussions with the safeguarding team.

If the assessment of the patient is that she is not competent to consent to testing, consideration should be given to whether she could be competent to consent to sexual activity. Patients aged 16 and over who are not competent to consent should be assessed in similar way from a safeguarding point of view.

When dealing with major trauma or a clinical emergency it may be impossible or inappropriate to determine pregnancy status through consented testing or enquiry prior to dealing with the patient’s condition. Where there is a chance that a patient may be pregnant the lead clinician should consider the radiological or clinical approach and relative balance of risk.

For example, acute abdominal pain could be due to an ectopic pregnancy and a positive pregnancy test will alert the clinician to this possibility. Whether or not testing or enquiry was carried out should be clearly documented with reasons if appropriate.

Post-procedural testing should only be carried out if on-going treatment would be affected by the patient’s pregnancy status.

Where a patient is undergoing a long-term course of treatment or attending frequently investigations it is expected that the clinician will make a judgement from his/her involvement with the patient whether ascertaining pregnancy status at each visit is appropriate. This decision should however always be documented.

The Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2000 state that there must be a procedure in place to check the pregnancy status of females of childbearing age.

The policy and procedure applies to all females aged 12-55 years who are to have radiographic examinations of the abdomen and pelvic areas.

The person requesting the examination (referrer) is responsible for ascertaining the patient’s pregnancy status.

The practitioner performing each radiographic or paediatric nuclear medicine examination is legally responsible for checking the date of the female patient’s last menstrual period (LMP). It is not necessary to check the LMP for someone only having plain x-rays of their chest or upper/lower limbs.

For low radiation dose examinations the 28 day rule applies (the examination should be performed within 28 days from first day of the last menstrual period.

Low radiation dose examinations include:

- X-rays of abdomen, pelvis and spine

- Barium meals/swallow and complex x-ray / interventional procedures involving no direct exposure to uterus

- Some paediatric nuclear medicine scans e.g. DMSA scans

For higher dose examinations the 10 day rule applies (the examination should be performed within 10 days from first day of the last menstrual period).

Higher radiation dose examinations include:

- CT scans of abdomen and pelvis

- Barium enemas and complex x-ray / interventional procedures involving direct exposure to uterus

- Some paediatric nuclear medicine scans e.g. bone scans, PET scans

The radiographer is legally obliged to check the patients last menstrual period dates immediately prior to the start of the examination. If the date is longer than the relevant 10 days or 28 days prior to the examination then the radiographer will contact the requesting clinician and refer the patient back for further discussions before the examination can proceed.

1. Checking pregnancy before surgery. NPSA, 2010

2. The use of routine pre-operative tests for elective surgery. NICE, 2003

3. Pre-procedure pregnancy checking for under 16s – guidance for clinicians. RCPCH, 2012

4. Pregnancy testing guidance; risks associated with anaesthesia and surgery in early pregnancy. RCPCH, 2012

5. Personal Beliefs and Medical Practice (2013) GMC.

6. 0-18 years: Guidance for all Doctors, GMC.

Last reviewed: 30 December 2021

Next review: 31 December 2024

Author(s): Dr Harriet Sansby

Co-Author(s): Corresponding author: Dr Graham Bell

Approved By: Paediatric & Neonatal Clinical Risk & Effectiveness Committee