The GUM team will classify the infant as ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’ depending on the factors above and will communicate this to the GP, obstetric and neonatal teams using the template letter in appendix 1. Ideally, this should also be documented on maternal clinical portal and badger record (under specialist review).

If mother has had a false positive syphilis result or has been confirmed to have previously treated syphilis, the infant needs no further examination above routine and needs no serology (bloods) performed at birth.

Sometimes maternal syphilis infection is not identified either because the mother was infected after booking bloods or was not tested during pregnancy. The first signs of infection are when the child is symptomatic, this can be months or even years after delivery. If a child is found to have syphilis this should be discussed with the local sexual health team to determine appropriate treatment and follow up and to arrange testing and treatment of parents.

All infants (low risk and high risk) whose mother has a true positive serological test for syphilis in this pregnancy need to be reviewed by the paediatrician shortly after delivery. Paediatrics need not attend delivery unless there are other indications. A detailed clinical evaluation is essential to look for signs of congenital syphilis as described above, recognising that two-thirds of infected infants will be asymptomatic.

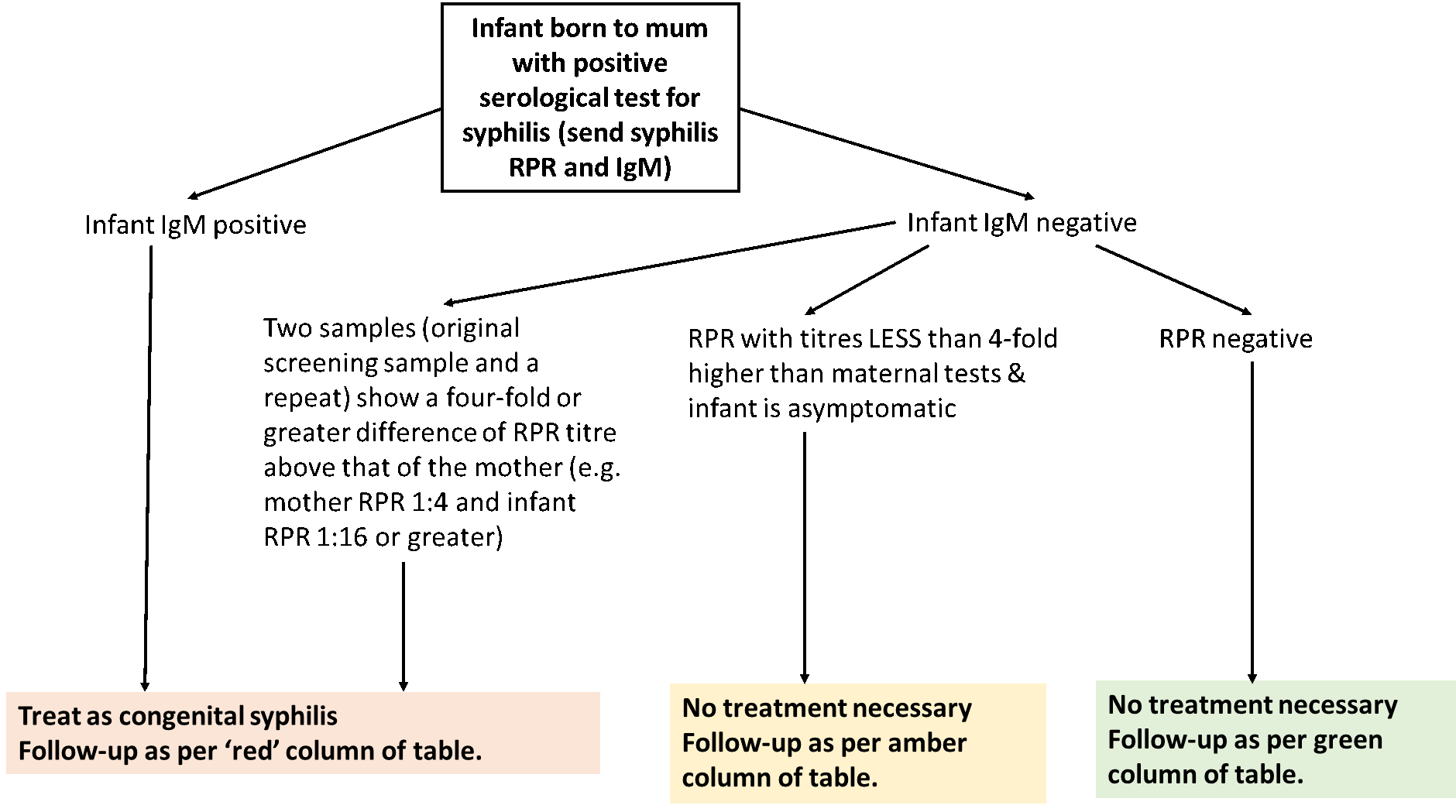

All infants (low risk and high risk) should have syphilis serology performed on infant serum (not cord blood) for TP Syphilis IgM (specific IgM suggests congenital infection as fetus can produce IgM from 24 weeks gestation) and RPR – this requires 2ml of blood in EDTA tube. These should be accompanied by a maternal venous bloods sample for comparison (for IgM and RPR).

High risk infants

Infants born to mothers with primary, secondary or early latent phase maternal disease are at high risk in the following circumstances:

Neonate:

- Signs of congenital syphilis (see above)

- Infant TP Syphilis IgM test is positive, together with corroborative history, clinical signs

- Infant has positive dark ground microscopy (see below)

- Infant has positive T pallidum PCR test (see below) together with corroborative history, clinical signs

Maternal factors - these will be highlighted in birth plan from GUM (appendix 1):

- High maternal RPR titres e.g. a titre of 1:16 or greater

- Inadequate course of maternal treatment as defined above

- Mothers with symptoms of primary syphilis shortly before delivery irrespective of the serological results.

These infants need the following investigations:

- FBC,U+E, LFTs

- HIV antibody if not known from maternal booking bloods.

- Lumbar puncture for CSF WCC, protein, RPR, TPHA (For RPR and TPHA: CSF fluid into white topped virology tube)

- Long bone X-rays for osteochondritis and periostitis

- Chest X-ray for cardiomegaly

- Cranial U/S scan

- Ophthalmology assessment for interstitial keratitis

- Audiology for 8th nerve deafness

If baby is symptomatic on examination, also perform:

- T pallidum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test – This test is done on any secretion or fluid from skin or oral lesions and fluid should be put into the white topped virology tube - discuss with the laboratory regarding sampling requirement prior to sending.

- Dark ground microscopy (DGM) – this is a test of fluid from a lesion on the skin. Fluid needs to be immediately placed on a slide and requires immediate interpretation so If this is required, discuss with the laboratory regarding sampling technique.