Sickle cell protocol

Objectives

Sickle Cell Disease is lifelong and can be life limiting. The condition is characterised by anaemia, episodes of acute painful crisis and an increased risk of infection. Clinical presentation and severity can be wide ranging.

Audience

Authorised personnel / specific staff competencies:

- The management of sickle cell disease will be directed by the Consultant or a senior member of the medical team.

- The Medical/Nursing team will be responsible for admitting, assessing, investigating and administrating treatment, and monitoring response.

Related Documentation:

- Anti-thrombotic Protocol (RHC-HAEM-ONC-007)

- Hydroxycarbamide Protocol & Consent Form (RHC-HAEM-ONC-051)

- Agonising pain (i.e. requiring parenteral opiate analgesia)

- Increased pallor, breathlessness, exhaustion

- Marked pyrexia (> 38oC), tachycardia or tachypnoea, hypotension

- Chest pain; signs of lung consolidation

- Abdominal pain or distension, diarrhoea, vomiting

- Severe thoracic/back pain

- Headache, drowsiness, CVA, TIA or any abnormal CNS signs

- Priapism (> 4 hours)

Inform on call haematology registrar of admission as soon as possible

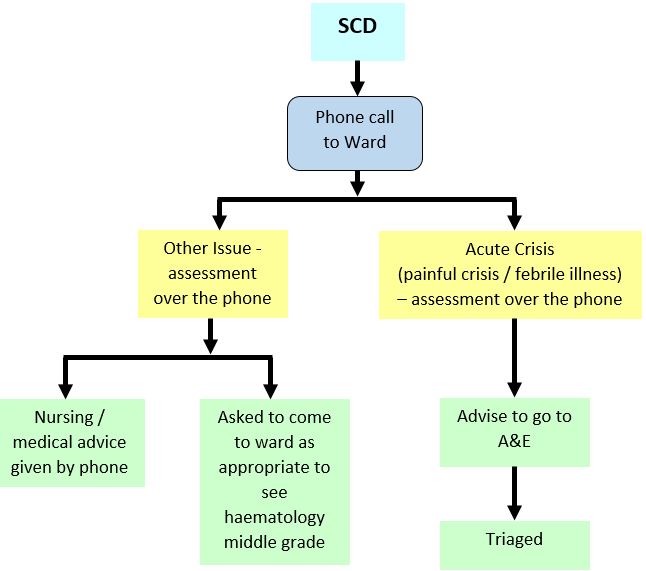

During normal working hours patients can be assessed and treated on the Ward 2B Day Care unit with admission to the ward as needed. Out of hours - see flow chart below. The Haematology Middle Grade On Call should be informed of their attendance and will arrange admission to the ward where necessary.

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD): Out with day care hours

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT:

A full history and examination must be carried out, paying particular attention to symptoms/signs of life-threatening complications, including acute chest syndrome, sequestration or aplastic crisis, or sepsis. Extreme pallor, weakness, lethargy, breathlessness, headaches, fits, and priapism require urgent attention.

Note:

- The site and intensity of the pain

- Any analgesia already taken

- Any focus of infection (including the urinary tract)

- Chest symptoms and signs, including respiratory rate

- Liver and spleen size (cm)

- Degree of pallor, blood pressure

DISCHARGE FROM CASUALTY OR WARD:

If there are no other indications for admission, following discussion with the Haematology Specialist Registrar, a child can be discharged from Casualty or from Day Care with:

- A supply of oral analgesia

- Instructions to drink a minimum of 50ml/kg/day

- Antibiotics if there is any evidence of infection (refer to hospital antibiotic policy)

- A follow-up appointment for review, within a week, either on Ward 2B Day Care (or the next Sickle Cell Clinic [Thursday PM])

- Folic acid

- Prophylactic Penicillin V (Erythromycin bd if Penicillin allergic)

ROUTINE INVESTIGATIONS (ALL CASES):

Blood Tests

- FBC and retics

- Group, screen and save

- Urea and electrolytes, bone profile

- Creatinine

- LFTs, LDH

- CRP

- Blood cultures

HbS % (only if on regular transfusion programme)

Microbiological Screen

- Urine dipstick and MSU culture

- Clotted blood to store

- Other cultures as indicated (see below)

Other Tests

- Pulse oximetry (SaO2) in air

- Chest x-ray if indicated (ie symptoms/signs)

ADDITIONAL INVESTIGATIONS:

Certain tests are done if indicated, as follows:

|

Test |

Indication |

|

Capillary or Arterial Blood Gases |

If deteriorating O2 sats in air |

|

Serum amylase Abdominal ultrasound |

Abdominal symptoms/signs Symptoms suggestive of cholecystitis |

|

Screen stool for Yersinia. Serum for Yersinia antibodies |

Patients on desferrioxamine (DFO) with diarrhoea/abdominal pain (STOP DFO) |

|

Erythrovirus B19 (Parvovirus) IgM serology and PCR |

Fall in Hb with low retics |

|

CT scan of head |

See stroke and other CNS complications |

|

X-rays of painful joints/limbs* |

Generally not helpful. See below |

|

ECG |

If possible arrhythmia or cardiac pain |

|

Throat, nose, sputum, stool, wound, CSF cultures etc |

As clinically indicated |

*X-rays of bones and joints show little or no change in the first week of an acute illness and rarely differentiate between infarction and infection. Ultrasound should be considered for suspected osteomyelitis. X-rays can be useful in confirming avascular necrosis as a cause of chronic or intermittent pain

INVESTIGATIONS (IF NEW TO THE HOSPITAL):

New patients to the hospital require all the routine investigations.

Additional Blood Tests

- Hb electrophoresis, including %HbF

- Full red cell phenotype - Rh, Kell, Fya+b, Jka+b

- G6PD

- Ferritin

- Hepatitis B and C serology

- CMV IgG

- Parvovirus serology

- Vitamin D

Consider HIV serology

Management is supportive unless there are indications for exchange transfusion. The aim of treatment is to break the cycle of: sickling, hypoxia and acidosis - all exacerbated by dehydration.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT INCLUDES:

- reassurance that the patient’s pain will be relieved as soon as possible

- warmth and establishing a position of maximum comfort

- analgesia

- hydration

- intravenous access if required for fluids, analgesia, antibiotics

- identification and treatment of infection

- regular observations and reassessment

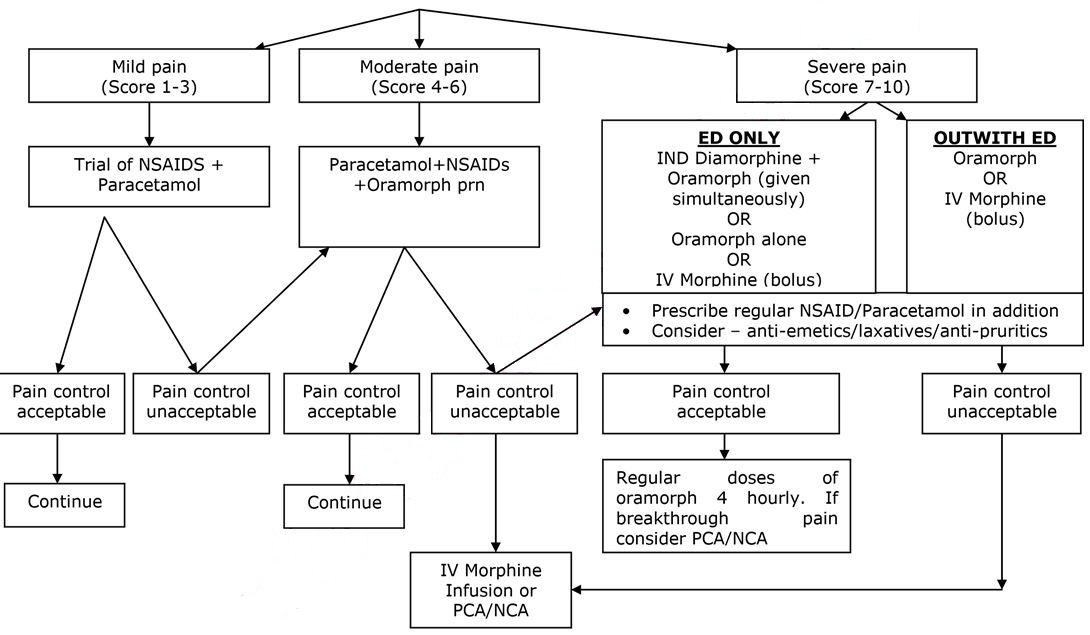

ANALGESIA – SEE FLOW CHART BELOW

- Pain is the commonest cause of hospital admission and needs to be addressed urgently. Analgesia should be administered within 30 minutes of arrival and aim for pain control within 60 minutes.

- Pain in sickle cell disease may be very severe, and is often underestimated by healthcare professionals.

- Assessment should include analgesia taken prior to attending hospital.

- Pain assessment should include the use of an age appropriate pain assessment score, which may be helpful as part of the overall assessment of the patient.

- Non Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents (NSAIDs) and Paracetamol may have synergistic effects and should be prescribed in addition to opiate analgesia.

Monitoring

The following should be monitored in all patients on analgesia:

- Severity of pain (use validated pain score)

- Sedation level

- Pulse, BP, temperature

- Respiratory rate

- Oxygen saturations in air

These observations should be performed at least every 30 minutes until the pain has been controlled and observations are stable, then according to local pain management protocols, or at least every 2 hours whilst the patient is on opiate analgesia. If the respiratory rate falls below 10/minute then any opiate infusion should be discontinued and consider the use of naloxone.

FIRST DOSE ANALGESIA SHOULD BE ADMINISTERED WITHIN 30 MINUTES

(FOR DOSES OF DRUGS REFER TO INFORMATION BELOW)

SEVERE PAIN

Intra nasal Diamorphine (IND) – if patient presents in ED –see below:

(For full guideline refer to Pain in children, management in the ED- “Guideline for using Intra nasal Diamorphine” 2015: Author Joanne Stirling).

It should be noted that IND and 1st dose of Oramorph should be given simultaneously. If IND contraindicated/unavailable, Oramorph or IV morphine should continue to be administered as per protocol.

Guideline for using Intranasal Diamorphine (to be used in conjunction with Emergency Department Pain Management Guideline)

Indications:

To be included as part of the first-line treatment of severe pain in a child (without IV access). For example, in children with pain secondary to:

- Clinically suspected limb fractures

- Painful/distressing burns

Contraindications:

- Need for immediate IV access (use parenteral morphine)

- Significant nasal trauma

- Blocked nose or upper respiratory tract infection

- Age < 1 year (or weight <10kg)

- General contraindications/sensitivity to diamorphine or morphine use

- Significant head injury

Protocol:

- Weigh the child in kg, transfer to resuscitation area (if not already done), monitor O2 sats

- Prescribe diamorphine via intranasal route (in mg) based on child’s weight (see chart – round to nearest weight; final dose=0.1mg/kg) and use chart (below) to determine the volume of water to add to a 5mg diamorphine ampoule. Mix well.

- Draw up 0.2 mls (0.1mg/kg) of the resultant solution into a 1ml syringe and discard the rest (following controlled drugs procedure).

- Gently tip child’s head and instill 0.1ml into each nostril (total of 0.2mls in drops). Occlude the other nostril after each 0.1ml and ask the child to sniff.

- Don’t forget to give supplementary oral analgesia (if not contra-indicated) and that the child may need ongoing IV analgesia once the initial pain is controlled.

- Intranasal diamorphine is usually effective within 5-10 minutes but allow up to 20 minutes for maximal pain control.

- Continue O2 sats monitoring for 1 hour post administration. Analgesic effect lasts up to 4 hours. Providing the child is stable, they can be transferred elsewhere within the department for ongoing monitoring once diamorphine has been administered.

Guideline for making up Intranasal Diamorphine Solution

Dilute 5mg of diamorphine powder with specific volume of sterile water

|

Weight (kg) |

Volume of sterile water to be added | Final dose in mg (in 0.2mls) |

|

10 |

1ml | 1mg |

|

11 |

0.9ml | 1.11mg |

|

12 |

0.85ml | 1.18mg |

|

14 |

0.7ml | 1.43mg |

|

16 |

0.6ml | 1.67mg |

|

18 |

0.55ml | 1.82mg |

|

20 |

0.5ml | 2mg |

|

25 |

0.4ml | 2.5mg |

|

30 |

0.35ml | 2.86mg |

|

35 |

0.3ml | 3.33mg |

|

40 |

0.25ml | 4mg |

|

≥50 |

0.2ml | 5mg |

Oral morphine:

|

From |

From |

Dose |

|

1 months |

2 months |

50 - 100 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response |

|

3 months |

5 months |

100 - 150 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response |

|

6 months |

11 months |

200 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response |

|

1 years |

1 years |

200 - 300 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response |

|

2 years |

11 years |

200 - 300 micrograms/kg (maximum 10mg) every 4 hours, adjusted according to response |

|

12 years |

17 years |

Initially 5-10mg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response |

Stat IV bolus of morphine (if required) once access established. This will take 5-20 minutes to take effect. Dose should be given by titration over at least 5 minutes to assess efficacy of dose.

|

From |

To |

Dose |

|

1 year |

18 years |

100 micrograms/kg/dose (max 5mg initially) |

When pain control is established consider continuous infusion. Refer to the Pain Team during working hours or to the Anaesthetist on call if out of hours for assessment.

Pain Relief Nurse Specialist: ext 84319/84320

Duty Anaesthetist: ext 84342/84842

Pain Consultant or on call consultant: check rota via switchboard or via extension 84316

Follow the Acute Pain Relief Protocol (APRS) V20 (Sep 2019)

NOTE: the decision to start a continuous infusion of an opioid or ketamine, or to modify doses and treatment remains with the Pain Team/Anaesthetists. The guidelines below have been included in this protocol to help with important information on safe monitoring of patients in the Ward who are managed with these drugs. Continuous follow up by the Pain Team/Anaesthetists for routine assessments and for advice on managing potential complications is required.

Efficacy of analgesia should be assessed repeatedly over the first few hours and adjusted if necessary. Patients will vary in their analgesic requirements.

Opioid Infusions:

Morphine sulphate is the first line opioid used in RHC, Glasgow. Oxycodone is the second line of opioid choice in RHC, Glasgow. However, Oxycodone can be considered as first line opioid choice in patients with Sickle Cell Disease who in previous admissions have experienced side effects to Morphine or better pain control with Oxycodone.

Intravenous Morphine/Oxycodone Infusion:

Dedicated anti-syphon/reflux infusion lines with maintenance fluids to ensure patency of cannula.

Morphine/Oxycodone syringe should be prepared as 1mg/kg in 50mls 0.9%saline

(≡0.02mg/kg/ml ie.20micrograms/kg/ml); maximum 50mg in 50mls

|

Initial IV Morphine / Oxycodone settings for paediatrics |

|

Self-ventilating Age : >3m: up to 0.020mg/kg/h ie. 20micrograms/kg/h ≡ 1ml/hr Ventilated in intensive care Up to 0.04mg/kg/h ie. 40micrograms/kg/h ≡ 2ml/hr |

Patient controlled Analgesia with Morphine / Oxycodone (PCA)

Dedicated anti-syphon/reflux infusion lines with maintenance fluids to ensure patency of cannula. However if the patient has PCA Accufuser, 6 hourly 0.9% N.Saline flushes should be prescribed to ensure patency on IV cannula.

Morphine / Oxycodone syringe should be prepared as 1mg/kg in 50mls 0.9%saline

(º0.02mg/kg/ml ie.20micrograms/kg/ml); maximum 50mg in 50mls (1mg/ml)

|

Initial IV PCA settings |

|

Bolus dose 0.020mg/kg ie. 20micrograms/kg ≡ 1.0ml. Maximum bolus dose 1mg (for 50kg+) Lockout interval 5 minutes Background infusion 0.004mg/kg/hr ie.4micrograms/kg/h ≡ 0.2ml/hr [useful in first 24h to improve sleep pattern] Omit if 50kg+ or if has had single shot epidural or regional block |

Nurse controlled Analgesia with Morphine / Oxycodone (NCA)

Dedicated anti-syphon/reflux infusion lines with maintenance fluids to ensure patency of cannula.

Morphine /Oxycodone syringe should be prepared as 1mg/kg in 50mls 0.9%saline

(≡0.02mg/kg/ml ie.20micrograms/kg/ml); maximum 50mg in 50mls (1mg/ml)

|

Initial NCA settings |

|

Age > 3m self-ventilating, or child of any age ventilated in intensive care Bolus dose 0.020mg/kg ie. 20micrograms/kg ≡ 1.0ml maximum bolus dose 1mg (for 50kg+) Lockout interval 20 minutes Background infusion 0.020mg/kg/h ie.20micrograms/kg/h ≡ 1ml/h |

KETAMINE INFUSION - This should only be undertaken by anaesthetists or trained pain management nurse specialist - if a trainee, discuss with your consultant and the pain team.

Minimum monitoring standard for patients - MAJOR analgesic techniques:

- Patients should be centrally monitored when on wards

- Use of DECT phones is required.

- One nurse per 4 patients.

- Continuous pulse-oximetry.

- Hourly pain assessment and nurse recordings using the appropriate chart which are available in clinical areas.

- Regular visits by pain relief nurse specialist and/or duty anaesthetists

Minimum monitoring standard for patients ALL OTHER analgesic techniques:

- Four hourly pain assessments should be carried out on the PEWS charts.

General points:

- Doses are a guide only and should be titrated with monitoring. The medical condition, surgical condition, age and maturity of the child should be taken into account.

- Any member of nursing or medical staff who have had appropriate training can perform refilling of opioid syringe.

- All children with epidural infusions, nerve infusions, NCA and PCA should have accompanying IV fluids for the duration of time the technique is running. However if the patient has PCA Accufuser, 6 hourly 0.9% N.Saline flushes should be prescribed to ensure patency on IV cannula

- Programming or reprogramming of PCA/NCA devices or epidural pumps should only be performed by the APRS and appropriately trained staff.

- Ensure all syringes, bags and lines for opioid or local anaesthetic infusions are correctly labelled.

- Ensure prescription is correctly and legibly written, signed, dated and timed on the additive label, in the drug Kardex and on the monitoring/prescription chart.

- Ensure the appropriate monitoring/prescription chart has all the requested information accurately completed, and accompanies the patient to the ward or unit.

- If in PICU, duplication of signs/recordings on the APRS chart is not required but fields not recorded on the PICU electronic record should be completed on the paper chart.

Beware!

All opioid and local anaesthetic infusions should be checked and signed by 2 practitioners.

Double check

- Drug dosages.

- Drug dilutions.

- Pump settings.

- Concurrent prescription of different opioids,

- All PCA/NCA must have an antisyphon line to prevent siphoning and reflux of opioid.

- Ensure opioid and epidural pumps not >20cm above patients head to prevent gravity free flow of infusion.

- Ensure obvious labelling of local anaesthetic infusions to avoid misconnections.

Injection or infusion of the wrong substances into epidurals or iv cannulae can be fatal.

Antagonists:

- Use Basic Life Support measures (ABC); give oxygen

For morphine antagonism:

|

|

Naloxone dose |

|

Excess sedation but SaO2>94% air Responds to pain stimulus |

2micrograms/kg iv stat; can be repeated every 60 seconds |

|

Excess sedation & SaO2 <94% in air Responds to pain stimulus |

10micrograms/kg iv stat |

|

Unresponsive |

20micrograms/kg iv stat |

Start an infusion, if required, at 10micrograms/kg/hr; use lowest effective dose:

|

For benzodiazepine antagonism: Flumazenil 5 micrograms/kg iv stat; Can be repeated every 60 seconds or start infusion at 10 micrograms/kg/hr Beware seizures precipitated by antagonists |

Moderate Pain:

- Oral Morphine (Oramorph) – see above for doses

- Oral Codeine – not used in RHC Glasgow

Mild Pain:

Oral Paracetamol:

|

From |

To |

Dose |

|

Neonate (32 weeks corrected gestational age and above |

20 mg/kg for 1 dose, then 10-15 mg/kg every 6 – 8 hours as required. Maximum daily dose to be given in divided doses (maximum 60mg/kg per day) |

|

|

1 month |

2 months |

30-60 mg every 8 hours as required. Maximum daily dose to be given in divided doses (maximum 60mg/kg per day) |

|

3 months |

5 months |

60 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

6 months |

1 year |

120 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

2 years |

3 years |

180 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

4 years |

5 years |

240 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

6 years |

7 years |

240 - 250 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

8 years |

9 years |

360 - 375 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

10 years |

11 years |

480 – 500 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

12 years |

15 years |

480 – 750 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

|

16 years |

17 years |

0.5 – 1 g every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day |

Oral Ibuprofen:

|

From |

To |

Dose |

|

1 months |

2 months |

5mg/kg 3-4 times daily |

|

3 months |

5 months |

50mg 3 times daily (maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses |

|

6 months |

11 months |

50mg 3 - 4 times daily (maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses |

|

1 years |

3 years |

100mg 3 times daily (maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses |

|

4 years |

6 years |

150mg 3 times daily (maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses |

|

7 years |

9 years |

200mg 3 times daily (maximum 30mg/kg to a maximum of 2.4g daily in 3 – 4 divided doses |

|

10 years |

11 years |

300mg 3 times daily (maximum 30mg/kg to a maximum of 2.4g daily in 3 – 4 divided doses |

|

12 years |

17 years |

300 - 400mg 3 - 4 times daily |

Fluids

Dehydration occurs readily in children with sickle cell disease due to impairment of renal concentrating ability and may aggravate to sickling due to increased blood viscosity. Diarrhoea and vomiting are thus of particular concern. Patients may also have cardiac or respiratory compromise and so fluid overload must also be avoided.

Careful assessment of individual fluid status, administration of an appropriate hydration regimen and close monitoring of fluid balance is therefore imperative.

The ill child should be assessed for the degree of dehydration by the history; the duration of the illness; by clinical examination; and (if known) weight loss. Hb and PCV (Hct) may be elevated as compared with the child's steady state values. These children normally have a low urea and so slight elevation is significant.

An IV line should be established whenever parenteral opiates have been given, or if the patient is not taking oral fluids well. In the less ill patient who is able to drink the required amount, hydration can be given orally. As an alternative consider a nasogastric tube in an alert patient.

IV hydration should be commenced on admission at maintenance rates or appropriate to individual fluid status. A fluid chart should be started and kept carefully, both input and output. Fluid balance must be reviewed regularly (at least 12 hourly) to correct dehydration and avoid fluid overload. Check urea and electrolytes at least daily and add KCl as required.

IV therapy can be stopped once the patient is stable and pain is controlled with documentation of adequate oral intake.

Calculation for Hyperhydration:

NOTE: only prescribe HYPERhydration if there is obvious clinical and laboratorial evidence of dehydration associated with the painful episode; if in doubt, prescribe MAINTENANCE IV fluid rates to begin with; if HYPERhydration prescribed, reassess fluid balance frequently and consider reducing fluids to MAINTENANCE rates whenever possible (usually within the first 24-48h).

|

Body weight (kg) |

Fluids (ml/kg/day) |

|

First 10 kg |

150 |

|

11- 20 kg |

75 |

|

subsequent kilograms over 20 |

30 |

For example: An 8kg infant will require 150 x 8 = 1200ml per 24hrs (50ml/hr) A 16kg child will require (150 x 10) + (75 x 6) = 1950ml per 24hrs (81ml/hr) A 36 kg child will require (150 x 10) + (75 x 10) + (30 x16) = 2730ml/24hrs (114ml/hr)

Electrolytes should be reviewed, remembering that a slightly raised urea will be significant as these children normally have a low blood urea.

- Check urea and U+Es at least daily and add KCl as required.

Oxygen

This is of doubtful use if the patient has only limb pain, but may be given if requested by the patient. The patient’s oxygen saturation (SaO2) should be monitored by pulse oximetry with regular readings in air (minimum 4 hourly).

- If SaO2< 95% in air, give O2 by face mask.

- Check capillary or arterial gases if SaO2in air is <90%.

- Monitor SaO2 while patient is on supplementary O2, aiming to keep SaO2> 98%.

- Inform consultant if deteriorating respiratory condition and consult acute chest syndrome protocol.

Physiotherapy

Children with Sickle Cell Disease should be referred for chest physiotherapy on admission if they:

- Have Acute Chest Syndrome

- Have had previous Acute Chest Syndrome

- Require IV opiate analgesia

- Are admitted for surgery (ie: splenectomy, abdominal surgery)

- Have back, chest, rib or abdominal pain

- Have X-ray changes

- Have clinical signs of infection

- Have decreased mobility

WORKING HOURS - Mon-Fri 09:00-17:00 - Contact the Respiratory Physio team by telephone in the first instance (ext: 84802, 08:30-16:30) and complete a Trakcare referral.

OUT OF HOURS – children with Sickle Cell Disease who have been admitted out of hours, are not critically unwell and fulfil any of the above criteria for referral, should be offered Incentive Spirometry on admission if able to do so, whilst awaiting Physiotherapy assessment the next working day (on completion of a Trakcare referral). Incentive spirometers with patient information leaflets on how to use it (and instructions on how to assemble and use the ‘bubbles’ incentive spirometer for younger children) can be obtained from the Haematology Ward, out of hours, by either calling Ward 6A (QEUH) directly on extension 84450 or by calling the Haematology Ward sister in charge on extension 84452. Critically unwell children with Sickle Cell Disease and chest signs should be referred and discussed with the Respiratory Physio on call on admission.

The SPAH network have published guidelines on Physiotherapy assessment and referral pathways.

Antibiotics

Infection is a common precipitating factor of painful or other types of sickle crises. These children are immunocompromised. Functional asplenia or hyposplenia occurs, irrespective of spleen size, resulting in an increased susceptibility to infection, in particular with capsulated organisms such as pneumococcus, neisseria, Haemophilus influenzae and salmonella – all of which can cause life-threatening sepsis.

- In uncomplicated painful crisis without specific evidence of infection increase prophylactic Phenoxymethylpenicillin (Penicillin V) to 4 times per day after cultures (blood, urine and any other source that is indicated) have been taken.

- If penicillin allergic, use erythromycin 4 times per day.

- Any unwell child with sequestration syndrome, chest syndrome or obviously toxic should receive intravenous antibiotics as per local antibiotic policy. Mild to moderately unwell children with a temperature of >38.0 should also receive intravenous Piperacillin Tazabactam (Tazocin) (or according to local antibiotic policy) after appropriate cultures have been taken.

- Dosing regimen: Piperacillin Tazabactam (Tazocin) (90mg/kg/dose 4 times a day)

- If there are chest signs, or an abnormal CXR, give Piperacillin Tazabactam (Tazocin) (IV) and clarithromycin (IV or oral) or Azithromycin (oral).

- If symptoms/signs of focal infection are present (eg tonsillitis, UTI), treat appropriately according to local microbiological advice.

- If penicillin allergic with a reaction classified as non-serious, use Ceftazidime (IV).

- If penicillin allergic with a reaction classified as serious (serious allergy is one that causes an anaphylactic or urticarial reaction, 10% of patients with reactions to penicillin-based antibiotics will also have a reaction with cephalosporins) use erythromycin (IV) or clarithromycin (IV) +/-ciprofloxacin.

- Patients on desferrioxamine (DFO) who have diarrhoea should be started on ciprofloxacin immediately (after checking they are not G6PD deficient) and the DFO stopped. Ciprofloxacin can be stopped if Yersinia infection has been excluded. Siblings of children with Salmonella infections should be discussed with the microbiology team.

Other Drugs

Please prescribe:

a) Folic Acid (oral)

|

From |

To |

Dose |

|

Birth |

1 month |

0.5mg once daily |

|

1 month |

12 years |

2.5mg once daily |

|

12 years |

18 years |

5mg once daily |

b) Anti-emetic: eg Cyclizine (if required with opiate analgesia)

|

From |

To |

Dose |

|

1 month |

6 years |

0.5-1.0 mg/kg 3 times daily |

|

6 years |

12 years |

25 mg 3 times daily |

|

12 years |

18 years |

50 mg 3 times daily |

c) Laxatives, if receiving opiate analgesia e.g. Lactulose, Senna, Macrogols – doses adjusted according to response

Lactulose:

|

From |

To |

Starting Dose |

|

1 month |

1 year |

2.5 mls 12 hourly |

|

1 year |

5 years |

5 mls 12 hourly |

|

5 years |

10 years |

10 mls 12 hourly |

|

over 12 years |

|

15 mls 12 hourly |

Senokot liquid (5mls= 7.5mg):

|

From |

To |

Starting Dose |

|

1 month |

2 years |

0.5ml/kg/dose at night |

|

2 years |

6 years |

2.5-5mls at night |

|

6 years |

12 years |

5-10 mls at night |

|

over 12 years |

|

10-20 mls at night |

d) Macrogols:

|

From |

To |

Dose (adjust to response) |

Product |

|

1 month |

1 year |

1/2 – 1 sachet |

Laxido Paediatric |

|

1 year |

6 years |

1 sachet |

Laxido Paediatric |

|

6 years |

12 years |

2 sachets |

Laxido Paediatric |

|

12 years |

adult |

1 – 3 sachets |

Laxido |

e) Antipruritic (if receiving opiate analgesia)

Oral Chlorphenamine Maleate (Piriton):

|

From |

To |

Dose |

|

1 month |

2 years |

1 mg twice daily |

|

2 years |

5 years |

1 mg 4-6 hourly |

|

6 years |

12 years |

2mg 4-6 hourly |

|

12 years |

adult |

4 mg 4-6 hourly |

Consider non-sedating antihistamines if sedated with Piriton

f) Iron chelation therapy – e.g. Desferrioxamine (if they would receive this normally)

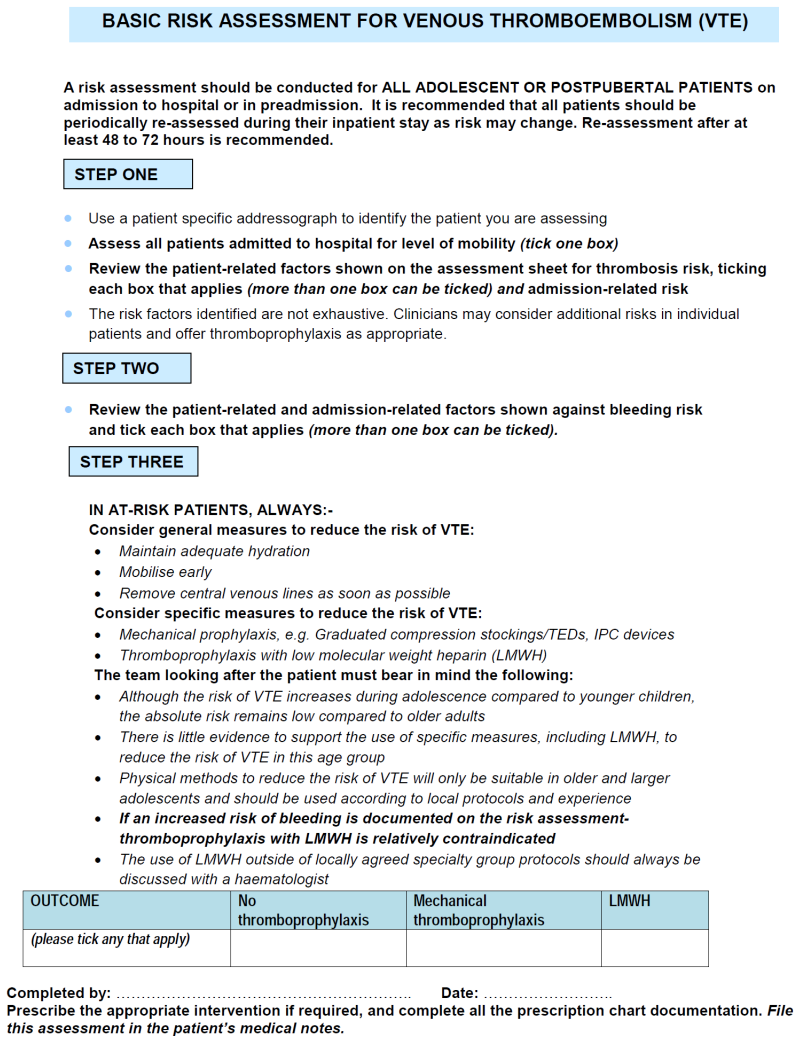

g) Thromboprophylaxis - LMWH (Clexane): consider in those ≥13yrs of age.

Please refer to Appendix 1 and also Section 5.10 of the Anti-thrombotic protocol (HAEM-007).

ABDOMINAL CRISIS AND GIRDLE SYNDROME:

Abdominal crises often start insidiously with non-specific abdominal pain, anorexia and abdominal distension. As abdominal pain is not an infrequent symptom in children, it can be difficult to diagnose. Constipation may often co-exist, especially if codeine or other opiates have been used as analgesia. In an abdominal crisis, bowel sounds are diminished, and there is often generalised abdominal tenderness; rebound tenderness absent. The abdomen is not rigid and moves on respiration. Vomiting and diarrhoea are less common.

Girdle (or mesenteric) syndrome may be said to be present when there is an established ileus, with vomiting, a silent distended abdomen, and distended bowel loops and fluid levels on abdominal x-ray. Some hepatic enlargement is common, and it is often associated with bilateral basal lung consolidation (early chest syndrome).

Differential diagnosis

Consider the possibility of surgical pathology such as acute appendicitis, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, biliary colic, splenic abscess, ischaemic colitis, peptic ulcer etc. Well localised or rebound tenderness, board-like rigidity or lack of movement on respiration are suggestive of these diagnoses. Ultrasound may be helpful. If surgical intervention is contemplated, exchange transfusion should be performed prior to laparotomy: this can be started pending clarification of the diagnosis.

Investigations

- FBC, biochemistry, CRP, blood cultures, group & save

- LFTs to exclude hepatic and biliary problems

- Serum amylase to exclude pancreatitis

- Plain abdominal x-ray & USS – as indicated

- Oxygen saturation & CXR

Management

- IV fluids: hyperhydration as for acute painful sickle crisis – monitor fluid balance carefully

- Analgesia: pain control as for acute painful sickle crisis

- Antibiotics eg cefuroxime and metronidazole (or as per hospital antibiotic policy)

- If there is vomiting, abdominal distension or absent bowel sounds, nil by mouth and consider nasogastric suction.

- Monitor abdominal girth (at umbilicus) 1-4 hourly; measure liver size bd.

- Monitor SaO2 in air. Measure capillary blood gases if SaO2 in air <90% repeat CXR and manage as per acute chest syndrome.

- Chest physiotherapy – incentive spirometry or other measures

Girdle syndrome may be an indication for top up or exchange transfusion – see ACS management.

ACUTE CHEST SYNDROME (ACS):

Acute sickle chest syndrome is an acute illness characterised by fever and / or respiratory symptoms accompanied by new infiltrates on chest x-ray.

It is likely to be multifactorial in origin. Sickling within the pulmonary vasculature leads to infarction and sequestration. Infection can precipitate or complicate ACS. The distinction between infection and sickling is difficult and management principles should be the same for the two conditions. Commonly pain in the thorax, upper abdomen or spine leads to hypoventilation, which may be exacerbated by opiate analgesia reducing respiratory drive. Basal hypoventilation leads to regional hypoxia which triggers localised sickling with subsequent infarction and consolidation. Thus a vicious circle is set up with sickling leading to progressive hypoxia and in turn to further sickling.

Acute chest syndrome is one of the major causes of death from sickle cell disease. A high index of suspicion is needed to detect and treat early. Patients should be treated aggressively irrespective of disease phenotype

Triggers

- Infection

- Painful vaso-occlusive crisis

- Post-operative

- Opiate induced hypoventilation

- Pulmonary embolus

- Fluid overload

Symptoms

- Pain (often pleuritic) in chest wall, upper abdomen and/or thoracic spine (T-shirt distribution).

- Dyspnoea

- Wheeze and cough which may be a late symptom.

Signs

- Fever,

- Tachypnoea, tachycardia, increased work of breathing.

- Hypoxia – a useful predictor of severity and outcome

- Signs of lung consolidation, including wheeze and bronchial breathing

Physical signs often precede x-ray changes.

Differential diagnosis

Sickle lung and pneumonia are often clinically and radiologically indistinguishable. However, consolidation in the upper and/or middle lobes, without basal changes, is suggestive of chest infection rather than sickle chest syndrome. Bilateral disease is most likely due to sickling, but atypical pneumonia should be considered. Pleuritic pain may also be due to spinal/rib/sternal infarction, or from subdiaphragmatic inflammation.

Investigations

- Baseline FBC, UE and creatinine and LFT, CRP

- Blood, throat and sputum cultures

- Chest x-ray – repeat if normal initially but ongoing clinical suspicion

- Respiratory viral infection screen – nose and throat swabs in viral transport medium for respiratory viruses and mycoplasma.

- Capillary blood gases if SaO2 < 94% - recommend pulse oximetry and CBG to monitor CO2/acid base if reqd

- Baseline HbS and extended phenotype cross match (if being considered for transfusion)

Markers of severity include worsening hypoxia, increasing respiratory rate, falling platelet count (<200), falling Hb and multilobar changes on chest x-ray

Management – General Measures

- Inform the Consultant on call for haematology at your regional referral centre if chest syndrome suspected. Discuss patients with PICU/HDU as early as possible

- Transfer of children in low prevalence paediatric units should be considered as soon as the condition is suspected. This may require transfer by the regional retrieval team dependent on the patient’s clinical condition

- Maintenance of adequate oxygenation is essential. Options include face mask oxygen, nasal cannulae, CPAP and ventilation. Ideally maintain SaO2>96%.

- Monitor oximetry on air at least 4 hourly together with pulse, BP and respiratory rate. Consider continuous pulse oximetry if clinical concerns and CBG

- IV fluids: individualised and guided by the patient’s fluid balance and cardiopulmonary status – (see below Fluid Management).

- Pain control: Ensure adequate pain control but with care to avoid opiate induced hypoventilation(see acute pain management guideline)

- Antibiotics: IV Piperacillin Tazobactam and oral azithromycin or clarithromycin (or as per local antibiotic policy).

- Physiotherapy: Incentive spirometry and other measures in conjunction with the physiotherapist. LINK

- Consider regular bronchodilators by nebuliser in patients with wheeze, demonstrable reversible airways obstruction or history of asthma

- Consider systemic steroids in severe ACS or acute asthma

Management – Transfusion

The purpose of transfusion is to:

- enhance oxygen-carrying capacity and improve tissue oxygen delivery

- reduce HbS concentration to reduce sickling

- prevent progression to acute respiratory failure

Transfusion commonly results in impressive improvement within hours.

Simple transfusion is indicated for patients with:

- mild or moderate chest syndrome, particularly with hypoxia and/or falling Hb levels

- aim for a post transfusion Hb level of 100-110g/l

Exchange transfusions are used to: o reduce the HbS concentration rapidly;

- avoid problems associated with increased fluid volume and viscosity.

- Exchange transfusion is indicated when there is evidence of:

- clinical and/or radiological deterioration despite simple transfusion o worsening x-ray changes o severe disease (see above)

Automated RBC exchange transfusion may be performed if available or using a manual method - Link for details of manual exchange procedure.

Fluid management

Dehydration occurs readily in children with sickle cell disease due to impairment of renal concentrating ability and may aggravate to sickling due to increased blood viscosity. Patients with acute chest syndrome also have respiratory compromise and may have cardiac compromise so fluid overload must also be avoided.

Careful assessment of individual fluid status, administration of an appropriate hydration regimen and close monitoring of fluid balance is therefore imperative.

The ill child should be assessed for the degree of dehydration by the history; the duration of the illness; by clinical examination; and (if known) weight loss. Hb and PCV (Hct) may be elevated as compared with the child's steady state values. These children normally have a low urea and so slight elevation is significant.

- An IV line should be established whenever parenteral opiates have been given, or if the patient is not taking oral fluids well. In the less ill patient who is able to drink the required amount, hydration can be given orally. As an alternative consider a nasogastric tube in an alert patient.

- IV hydration should be commenced on admission at maintenance rates or appropriate to individual fluid status.

- A fluid chart should be started and kept carefully, both input and output.

- Fluid balance must be reviewed regularly (at least 12 hourly) to correct dehydration and avoid fluid overload.

- Check urea and electrolytes at least daily and add KCl as required.

- IV therapy can be stopped once the patient is stable and pain is controlled with documentation of adequate oral intake.

For more comprehensive guidance please refer to the BSCH Guideline on the Management of Acute Chest Syndrome in sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 2015 169 492-505

APLASTIC CRISIS:

A temporary red cell aplasia caused by B19 (Parvovirus) can lead to a sudden severe worsening of the patient’s anaemia. A viral prodromal illness may have occurred, but classical erythema infectiosum (‘slapped cheek syndrome’) is uncommon.

The main differential diagnosis is splenic sequestration. Aplastic crisis may affect multiple members of a family concurrently or consecutively.

Diagnosis

- Rapidly falling Hb

- Reticulocytopenia (but retics may be increased if in early recovery phase)

- B19 (Parvovirus) IgM present (or PCR positive although this may not always indicate acute infection)

Management

- Urgent red cell transfusion may be necessary (if Hb < 6g/dl)

- Spontaneous recovery is heralded by return of nucleated RBCs and reticulocytes to peripheral blood

- Recurrence does not occur, as immunity to Erythrovirus is lifelong

Comprehensive RCPCH guidance on the diagnosis, management and rehabilitation of children and young people with stroke and specifically secondary to sickle cell disease is available and should be consulted.

Acute Ischaemic Stroke (AIS):

Stroke is a potentially devastating complication of sickle cell disease. It is commonest in individuals with HbSS, when it occurs in up to 10% of patients without primary prevention. Vaso-occlusion of the cerebral vessels leads to infarction, generally in the territory of the middle cerebral artery, and untreated the majority will have a recurrence. Assessment using the FAST criteria (below) identifies 88% of anterior circulation strokes in children.

Predictive factors for stroke include those with a history of transient ischaemic attacks, chest syndrome, hypertension, a family history of sickle related stroke, or those with a low Hb F and/or low total haemoglobin.

The Stroke Prevention Trial (STOP) showed that children with transcranial Doppler (TCD)

velocities of >200cm/sec are also at significant risk and should be offered primary prevention with chronic transfusion.

Presentation

Acute onset focal neurological deficit

- Assess using the FAST criteria: >= 1 of facial weakness, arm weakness or speech disturbance

Altered level of consciousness or behaviour

- Assess using AVPU less than V or GCS less than 12

The following symptoms may also be indicative of stroke

- New onset seizures

- Severe new onset headache

- New onset ataxia, vertigo or dizziness

- Sudden onset of neck pain or stiffness

- Witnessed acute focal neurological deficit which has since resolved

Investigations

- Urgent (<1 hour of arrival in hospital) unenhanced CT of brain

- Subsequent MRI/A including head and aortic arch) (this can be performed as initial investigation if available within 1 hour of presentation)

- Consider CTA of head to guide urgent intervention in haemorrhagic stroke.

- Initial CT may be useful to exclude haemorrhage, but may be negative in the very early stages. If clinical findings are consistent with stroke then arrange urgent MR within 24 hours or treat according to clinical suspicion

- Pre-exchange investigations as per exchange transfusion protocol

- Glucose level

Lumbar puncture may be necessary to exclude infection or subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Management

Immediate:

- Urgent neurological assessment in conjunction with neurology team

- Regular monitoring of conscious level by GCS or AVPU and neurological status by PedNIHSS assessment tool.

- Monitor temperature, heart rate, BP, RR, SaO2 and aim to keep SaO2>94%,

- Withhold oral feeding until safe swallow has been established

- Maintain normal fluid and electrolyte balance

- Exchange transfusion urgently, aiming to achieve HbS below 20%, with target Hb 100-110g/l, ideally by automated red cell apheresis.

- Provide top up transfusion to Hb100g/l to improve oxygenation if exchange is likely to be delayed by >6 hours or if stroke occurs in the context of acute anaemia

- For patients in centres where automated exchange is not available consideration should be given to stabilisation and transfer

- Seizures may occur and require anticonvulsant therapy

- Early multidisciplinary functional assessment (as soon as possible and within 72 hours) by physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy (PT/OT/SLT)

- Aspirin should be avoided routinely and exchange transfusion should be prioritised over thrombolysis

Long term

- Liaison with multidisciplinary community allied health professionals to support discharge and rehabilitation

- A regular transfusion programme as secondary stroke prevention should be instituted with target pre-transfusion Hb >90g/l and HbS level <30%

- Monitor children with regular neurocognitive testing, MRI/A and TCD.

- Intensify therapy if monitoring identifies progressive cerebrovascular disease

- Options include lower HbS target, addition of hydroxycarbamide or antiplatelet agents, surgical revascularisation or HSCT. All children and their siblings should be tissue typed.

- Those with recurrent stroke or worsening vasculopathy despite optimum haematological management should be considered for stem cell transplant or surgery and discussed at an appropriate MDT.

- Hydroxycarbamide can be considered when transfusion is not possible

Transient Ischaemic attacks (TIA):

- Initiate prompt evaluation, including neurologic consultation and neuroimaging studies, in people with SCD who have a recent history of signs or symptoms consistent with transient ischemic attack.

- TIA is a strong risk factor for subsequent stroke; if history and investigations are consistent with TIA then consider acute management as per stroke guidance.

Silent Cerebral Infarctions (SCI):

The possible benefits of transfusion should be discussed with young people and their families if SCI are identified on MRI. Additional factors favouring a transfusion programme are:

- impaired cognitive performance or progressive deterioration

- evidence of increase in the size or number of SCI on serial MRI

- evidence of intracranial or extracranial vasculopathy on MRA

- other co-morbidities exist which may benefit from regular transfusion

Consider hydroxycarbamide if transfusions are declined or contra-indicated

These patients should be discussed at an MDT and HSCT may be considered.

Haemorrhagic Stroke (HS):

Sickle cell disease is associated with an increased risk for haemorrhagic stroke including subarachnoid haemorrhage and recurrence of HS.

Subdural and extradural haemorrhage are under recognised complications in sickle cell disease and can occur in the absence of trauma related to hypervascular bone, bone infarction or venous thrombosis

Investigations

- As per acute ischaemic stroke

Management

- Urgent neurosurgical input is indicated

- Management and supportive care as for acute ischaemic stroke including exchange transfusion

- To prevent recurrence, neuroimaging as for acute HS in children and young people without sickle cell disease is indicated (see RCPCH guideline). Consider exchange transfusion prior to direct intra-arterial contrast injection.

- Refer to RCPCH guideline for further information on prevention of recurrence

Convulsions:

Febrile convulsions may occur with high fevers, including after vaccination, however it is important to distinguish these from convulsions due to acute stroke.

Investigations

- Urgent CT/CTA (or MRI/A) to exclude acute haemorrhage or ischaemia.

- Blood cultures and other infection screen including LP as clinically indicated

- Consider EEG in consultation with neurology team

Management

Immediate:

- Anticonvulsant, as per local hospital protocol

- Antipyretic, such as paracetamol

Definitive

- If no abnormality on EEG and CT/MRI and MRA, and no recurrence, watch and wait.

- If EEG abnormal, but CT/MRI and MRA are both normal, consider anticonvulsants.

- If silent infarction is detected on scanning, or vessel stenosis/occlusion on angiogram then see management for silent cerebral infarction above.

Meningitis:

Presentation

Fever, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia

Investigations

Urgent CT/CTA (or MRI/A) to exclude acute haemorrhage or ischaemia.

Lumbar puncture and blood culture

Management

As per local antibiotic policy

Splenic Sequestration:

Splenic sequestration is more common in infants and young children (< 3 years old).

It may be precipitated by fever, dehydration or hypoxia. Rapid sequestration of red cells can lead to sudden anaemia and even death from hypoxic cardiac failure with pulmonary oedema. In some patients, it may have a more insidious onset and can be recurrent.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain (pulling legs up to abdomen)

- Abdominal distension

- Sudden collapse

Signs

- Rapidly enlarging spleen (may or may not be painful)

- Pallor, shock (tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnoea)

- +/- Fever due to associated sepsis

Investigations

- FBC and retics (raised in sequestration, cf absent in aplastic crisis)

- Blood cultures and other infection screen, as clinically indicated

- Parvovirus serology (differential diagnosis is aplastic crisis)

- Cross match half the patient’s estimated blood volume immediately

Management

- Assess the need for volume expansion but crystalloid should be used with caution as it may exacerbate cardiac failure

- Emergency top-up transfusion, if necessary with uncross-matched O Rh -ve blood

- Broad spectrum antibiotics eg Tazocin (or as per local antibiotic policy)

- Before discharge, teach parents to recognise the symptoms and to detect an increase in spleen size

- Consider a regular transfusion regime for 2-3 months

- Consider splenectomy if recurrent (> 1 episode)

Hepatic Sequestration:

Symptoms

- Right hypochondrial pain, abdominal distension

- +/- Fever due to associated sepsis

Signs

- Enlarging tender liver, increasing jaundice

- Collapse/shock is less common than with splenic sequestration

Investigations

- Bilirubin may be very high

- Exclude gallstones/cholestasis by ultrasound

- Blood cultures and other infection screen, as clinically indicated

Management

- May need urgent top-up transfusion

- IV Tazocin or other broad spectrum antibiotic as per local antibiotic policy

- If the patient becomes tachypnoeic, or develops chest signs, then check oxygen saturation and treat as for acute chest syndrome

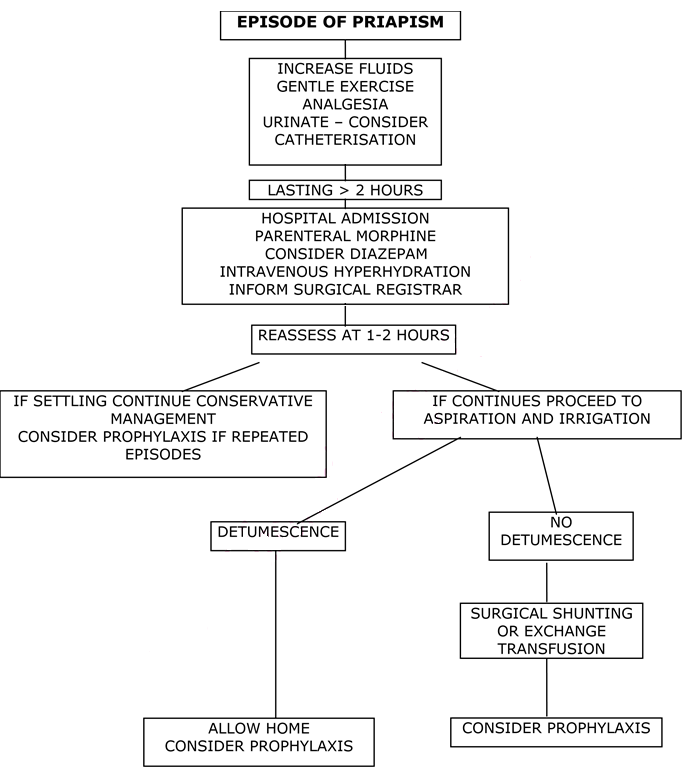

Priapism is defined as a sustained painful erection and is one of the vaso-occlusive complications of sickle cell anaemia. The prevalence of severe priapism in sickle cell is unknown but a survey in young males suggested that 89% will experience priapism by 20 years of age and 25% of children with sickle cell disease related priapism are pre-pubertal.

Priapism can be acute/fulminant or stuttering:

Acute / Fulminant Priapism

- Severe pain

- Duration >4 hours

- Penis fully erect

- High risk of cavernosal fibrosis and impotence

- Urgent intervention indicated

Stuttering Priapism

- Recurrent

- Pain of variable intensity

- Lasting 30 minutes to < 3hours

- Penis may not be fully erect

- Risk of subsequent fulminant attack

The optimal management of priapism is still a subject of debate. This protocol is based on a recent review of the literature.

Aims of Treatment

The aim of treatment is threefold:

- Achieve rapid relief from pain and discomfort

- Preserve potency

- Prevent recurrence

Outcome is dependent on the pubertal status of the patient and length of time to detumescence. Poor long term outcome in terms of impotence is associated with post-pubertal males and a long duration of erection. The likelihood of responding to intervention is also related to duration of erection with most procedures being most effective in the first 6 hours and relatively ineffective after 24-48 hours. Hence, PRIAPISM IS A UROLOGICAL EMERGENCY requiring rapid assessment and treatment to prevent irreversible ischaemic penile injury, corporal fibrosis and impotence.

Patient Education

Male sickle cell patients and their families should be educated about priapism early after diagnosis or transfer to the service and written information should be given. Specific enquiry should be made about this symptom at follow-up. They should be instructed to present to hospital immediately if an episode of priapism does not resolve within 2 hours.

History and examination

- Duration of episode

- Pain severity (usually very painful)

- Medications including alcohol and recreational drugs, analgesia

- Prior episodes

- Crisis pain elsewhere

- Abdomen – masses, spleen, bladder, external genitalia

- Full set of observations including SaO2

Investigations

- Full blood count

- Urea and electrolytes and creatinine

- Group and save with extended red cell phenotype

General Principles of Early Management

- Attempt to urinate (consider catheter if unsuccessful and a full bladder is present)

- Try a warm bath

- Gentle exercise

- Hydration

- Analgesia

Management Plan for Acute/Fulminant Priapism

- A review of the literature suggests procedures such as exchange transfusion are of little value in the acute setting and only delay definitive treatment. The treatment of choice is aspiration and irrigation, which should be performed with 4-6 hours of onset. Therefore, urgent involvement of paediatric surgeons/urology is needed and this should not be delayed while initial supportive measures are carried out.

- Initial management should be: intravenous hyperhydration (1.5-2 x normal maintenance fluids) and analgesia (morphine is usually needed). Sedation may be useful in some cases – take care with concomitant opiate use.

- NB Acute exchange transfusion is generally not indicated and has been associated with an increased incidence of neurological events (ASPEN Syndrome). Top-up transfusion may be associated with similar concerns and should only be considered if otherwise indicated by the clinical picture.

- If there is no detumescence after 1-2 hours then aspiration and irrigation should be performed (see protocol).

- Irrigation can be performed with epinephrine (1:1 000 000) OR 1% Phenylephrine OR 5mg of undiluted Etilefrine can be instilled intracavernosally at the end of the procedure. See Table 1.

- Aspiration and irrigation is reported to be effective in more than 85% of cases. Failure is usually associated with prolonged episodes of priapism >24 hours. Second line management consists of exchange transfusion and/or formal surgical shunting operations such as Winter’s cavernosal shunt performed under general anaesthesia.

- If aspiration is successful then the patient should be observed for a few hours and then, if well, discharged home.

- If the patient has had previous episodes of priapism then medium to long term prophylaxis should be discussed (see stuttering priapism below).

Procedure for Aspiration and Irrigation

- Aspiration can be performed under sedation/general anaesthesia depending on the age of the patient.

- If not under GA then using an aseptic technique infiltrate 0.5ml 1% Lignocaine under the skin on the lateral aspect of the penis.

- Insert a 23-gauge needle or butterfly into the corpus cavernosum with a lateral approach taking care to avoid the dorsal vein (superior aspect) and the urethra (inferior aspect). Attach a 3-way tap and aspirate into a dry 10ml syringe: 3–5-mL aliquots should be aspirated until bright red (oxygenated) blood is seen (not exceeding 10% of the circulating blood volume; 7.5 mL/kg in children aged ≥1 year). The corpora should then be flushed with warmed 0.9% saline. The procedure is unilateral as there is a connection between the two corpora.

- If aspiration and irrigation do not achieve detumescence, sympathomimetic intracorporal injection should be performed with cardiovascular monitoring: pulse, BP and pulse oximetry should be monitored at 15 minute intervals until >30 minutes post-procedure. Side-effects are rare but include headache, dizziness, hypertension, reflex bradycardia, tachycardia, arrhythmias. Injections must stop when detumescence is achieved.

- If Epinephrine is being used: then attach another 10ml syringe containing a 1:1 000 000 solution of Epinephrine (i.e. 1ml of 1:1000 Epinephrine diluted in 1 litre 0.9% sodium chloride) to the 3 way tap and irrigate with this solution. If needed additional blood can be aspirated until detumescence occurs.

- If Etilefrine is being used: then attach a 10ml syringe containing 0.9% sodium chloride to the 3 way tap and irrigate. Additional blood can be aspirated until detumescence occurs. 5mg (0.5ml) of undiluted Etilefrine can be instilled into the corpora via the 3-way tap at the end of the procedure (NB irrigation is not always required prior to etilefrine instillation).

After withdrawal of the needle firm pressure should be applied for at least 5 minutes to prevent haematoma formation (the most common complication of the procedure)

Table 1 (adapted from Donaldson et al 2014)

|

Drug |

Available Preparations |

Concentration |

Age and aliquot |

Further doses |

|

Epinephrine |

1 in 10,000 |

1 mL + 99 mL 0.9% saline (1 in 1 000 000 or 1 μg/ml) |

≥ 11 yrs: 15 mL 3-11 yrs: 10 mL <2 yrs: 2.5-5 mL |

≤4 doses at 10 min intervals |

|

1 in 1000 |

1 mL + 1000 mL 0.9% saline (1 in 1 000 000 or 1 μg/ml) |

|||

|

Etilefrine |

10 mg/mL |

None |

0-18 yrs: 0.5 mL |

≤2 doses at 10 min |

|

Phenylephrine |

10 mg/mL |

0.1 mL + 4.9 mL 0.9% saline (200 μg/ml) |

≥ 11 yrs: 0.5 mL |

≤10 doses at 5-10 min (max 1 mg) |

Suggested sympathomimetic preparation for intracorporal injection (ICI). This is an unlicensed indication and route of administration. When available Phenylephrine should be used in boys aged ≥11 years; Epinephrine should be used in boys ≤10 years. There are no reliable data on ICI ≤2 years: we recommend using a reduced dose of Epinephrine (Adrenaline).

Management of Stuttering Priapism

- Initial treatment out of hospital should consist of:

- Increased fluid intake

- Oral analgesia

- Gentle exercise

- Attempts to urinate soon after onset

- If the episode lasts more than 2 hours then the patient should be advised to attend hospital at once and acute priapism protocol should be followed.

- Prophylaxis should be discussed with the patient and parents. Options are:

- Exchange Transfusion Programme

- Oral Etilefrine (an α- agonist)

- Hydroxyurea

An exchange transfusion programme has the disadvantages of potential iron overload, alloimmunisation, difficulties with venous access and repeated hospital visits but has the advantages of reducing other sickle related morbidity during the period of transfusion.

Etilefrine is a direct acting alpha-adrenergic agonist. In normal physiological circumstances adrenergic impulses keep the penis flaccid in the absence of sexual stimulation.

Etilefrine has advantages over other alpha agonists such as epinephrine and phenylepinephrine in that it is rapidly absorbed orally and has a short half life (150 minutes) and it may have a lower risk of systemic hypertension. It appears effective in small trials but there is only limited experience in children. Systemic hypertension has not been seen in paediatric patients reported in the literature but should be assessed regularly on treatment.

Etilefrine is given in a dose of 0.5mg/kg daily. This can be given as one dose of 0.5mg/kg in the evening for patients with nocturnal priapism or 0.25mg/kg twice daily in other patients. It will not reduce other sickle cell related symptoms.

Hydroxycarbamide has been shown to be effective in reducing sickle related complications in children. There are case reports documenting its efficacy in treatment of recurrent priapism but this outcome was not studied in the large scale trials reported to date. It has the advantage of preventing other sickle related morbidity and reducing need for transfusion. Regular blood count monitoring is required throughout treatment and potential long term adverse effects are unknown.

Haematuria:

Microscopic haematuria is common in sickle cell disease; macroscopic haematuria may be due to urinary infection or papillary necrosis. Passing of renal papillae may cause renal colic and ureteric blockage. Haematuria can also occur in patients with sickle trait.

Investigations

- MSU for culture to exclude infection

- Ultrasound scan

- Hydrated intravenous urography may be necessary to establish the diagnosis, discuss with registrar or consultant first

Nocturia and enuresis:

Nocturia and enuresis are common in part due to obligatory high fluid intake, coupled with reduced urinary concentrating capacity. Cultural and familial influences may also play a part.

Reassurance, patience, and measures such as reward systems, bell and pad training, etc may be required. Referral to a local Enuresis Clinic or to the clinical psychologist may be appropriate.

Urinary tract infections:

Not uncommon in sickle cell disease, in both sexes. It should be vigorously investigated and treated to prevent serious renal pathology. Haematuria, secondary to papillary necrosis, can precipitate UTI, but other factors must be excluded.

Chronic renal failure:

Uncommon in children. Predictors include increasingly severe anaemia, hypertension, proteinuria, the nephrotic syndrome, and microscopic haematuria.

Investigations

- Urea and electrolytes, calcium, phosphate, bicarbonate; immunoglobulins and autoantibodies.

- FBC and reticulocytes

- MSU for M,C and S; 24 hour urine collections for protein and creatinine clearance

- Ultrasound of kidneys and urinary tract

Management

- Refer to renal team

- Consider erythropoietin and/or hypertransfusion regime

The ocular complications due to sickle cell disease are uncommon in children, however retinal vessel occlusion may begin in adolescence in particular in children with HbSC disease. Thus these children require annual ophthalmological assessment from puberty onwards. Also, children on regular transfusion regimens receiving desferrioxamine require annual ophthalmological assessment.

Management:

- Refer to Ophthalmology

Laser therapy is the treatment of choice for proliferative sickle retinopathy. Vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment may occur.

Surgical treatment should not be undertaken without prior exchange transfusion.

Gallstones:

Pigment gallstones due to ongoing haemolysis are common in sickle cell disease, occurring in at least 30% of children. It is often asymptomatic but can precipitate painful abdominal crises and the girdle syndrome. It can also cause:

- Acute cholecystitis

- Chronic cholecystitis

- Biliary colic

- Obstruction of the common bile duct

- Acute pancreatitis

Differential Diagnosis of abdominal complications:

- Hepatic or splenic sequestration

- Acute chest syndrome

- Surgical pathology - consider e.g. acute appendicitis, splenic abscess, ischaemic colitis, peptic ulcer etc. Well localised or rebound tenderness, board-like rigidity or lack of movement on respiration are suggestive of these diagnoses

- Constipation

Investigations

- FBC, Biochemistry, CRP, Blood cultures, Group & Save

- LFTs to exclude hepatic & biliary problems

- Serum amylase to exclude pancreatitis

- Plain abdominal X-rays & USS - as indicated (50% of gallstones are radio-opaque)

- Oxygen saturation & CXR chest

Management

Acute episode of cholecystitis:

- Analgesia

- Hydration

- Antibiotics- cefuroxime and metronidazole

Recurrent episodes of cholecystitis is an indication for cholecystectomy (see below):

Common bile duct obstruction:

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or emergency surgery. After one attack, refer for surgical opinion re elective cholecystectomy; generally laparoscopic, which does not require prior transfusion, however it may be best to exchange in case full laparotomy becomes necessary.

Intrahepatic cholestasis:

Some patients experience episodes of severe hyperbilirubinaemia (conjugated + unconjugated) with moderately raised alkaline phosphatase, associated with fever and hepatic pain in the absence of demonstrable stones. These episodes are thought to be due to severe intrahepatic sickling.

Management

- Analgesia (care as most opiates are metabolised in the liver)

- Hydration

- Antibiotics; e.g. cefuroxime

- Monitor liver function tests, and as for girdle syndrome/hepatic sequestration

- Hyperhaemolysis +/- sequestration may supervene, requiring frequent transfusion

- In severe cases, exchange transfusion may be needed

This complication may start in adolescence and often gives rise to chronic pain and limitation of movement due to joint damage, rather than ongoing vaso-occlusion.

Presentation:

- Pain in the hip, leg groin, knee or shoulder on movement; later at rest. Repeated or prolonged pain (>8 weeks) should be investigated for aseptic necrosis

- Limitation of movement; particularly abduction and external rotation of the hip, external rotation of the shoulder

Differential diagnosis:

- Osteomyelitis

- Septic arthritis

These are suggested by swinging pyrexia, severe systemic disorder, positive blood cultures and toxic granulation in neutrophils.

Investigations

- X-ray

- MRI (This will show changes much earlier than x-ray)

- Isotope bone scan can be very difficult to interpret in the presence of active sickling

Management

- Analgesia with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents or codeine derivative.

- Rest and the avoidance of weight bearing (very difficult to implement).

- Transfusion cannot reverse the process but may prevent progression to the contralateral joint; it is performed pre-operatively and for 3 months post-operatively to maximise bone healing.

- Refer for orthopaedic assessment and treatment (Mr Duncan), which is likely to involve these types of treatment:

- Osteotomy and/or decompression surgery may be considered.

- Major joint surgery may be necessary if pain is continuous (>2 years) or very severe, or if the patient’s mobility is seriously affected.

- Different types of prosthesis, hip fusion, or bone grafting are used depending on the individual case. Cemented prostheses are best avoided. Loosening of the prosthesis is quite common. Infection is not uncommon.

- The possibility of failure, the likelihood of some residual pain, the potential life of the prosthesis, and the limitations imposed must always be discussed with the patient pre-operatively.

Delayed puberty:

- Common, particularly in boys

- Related to lower body mass for age in children with sickle cell disease

- Reassure, as most will progress to puberty and achieve normal height despite the delay

Management

- In the very thin patient, attempt to improve the appetite and quality of nutrition in order to increase the body weight

- If an endocrine review is appropriate, or replacement therapy needed then refer to Prof Ahmed

- Regular transfusion for 6 - 12 months almost always initiates puberty delayed due to sickle cell disease

(Exceptionally, infarcts in the hypophysis and hypothalamus are responsible)

Fertility:

Girls are normally fertile, whereas many boys with HbSS and S/Beta thalassaemia have reduced sperm counts and reduced sperm motility - some may have erectile impotence because of past priapism.

Anaemia alone in an otherwise well child is not an indication for transfusion unless the haemoglobin falls to less than 5g/dl, in which case discuss with Senior Trainee/Consultant. To prevent red cell alloimmunisation Rh and kell compatible blood should be used whenever possible. All patients should have red cell phenotyping done at diagnosis.

Options for transfusion include simple additive transfusion, exchange transfusion and hypertransfusion regimens. All regularly/heavily transfused patients should be monitored for iron overload.

Simple or “top-up” transfusion:

This is indicated for acute symptomatic anaemia eg aplastic or sequestration crises, or acute bleeding. It may also be indicated pre-operatively (see p36). Do not transfuse to above 11g/dl. Volume required:

- Weight in kg x desired rise in Haemoglobin x 3 = volume in mls to transfuse

Exchange Transfusion:

Exchange transfusion is undertaken to rapidly reduce the percentage of sickle cells in the circulation when a patient develops a life-threatening complication of the disease and when a simple ‘top up’ transfusion is deemed not appropriate in the particular clinical scenario. The decision to proceed with an exchange transfusion should be taken following discussion with the Paediatric Haematology Consultant on call as the procedure is not without possible complications. Indications for exchange transfusion in patients with sickle cell disease include:

- Severe acute chest syndrome – see ACS protocol for indications

- Girdle syndrome

- Acute stroke (or as part of primary/secondary stroke prevention)

- Multi-organ failure syndromes

- Electively, in preparation for planned surgical procedures in selected cases

Aims

- To reduce the % HbS to < 20% over 2-3 days unless acutely ill, when more rapid exchange may be appropriate

- To keep Hb < 100g/l initially (or at steady state level in those with higher baseline Hb, e.g. HbSC patients) and about 100-110g/l (PCV 0.36) by the end of the whole procedure.

- To maintain a steady state blood volume throughout the procedures

Preliminary Investigations

- FBC

- % HbS (or S+C if HbSC disease)

- Extended RBC phenotype (if not already known), cross-match and antibody screen (ensure that the blood transfusion laboratory is aware that the blood requested is for a child with a haemoglobinopathy AND for exchange transfusion so unit specifications can be met)

- Urea and electrolytes, creatinine, calcium

- Capillary or arterial blood gases - in those with symptoms suggestive of chest or girdle syndrome

- Baseline Serology for Hepatitis B and C and HIV, if not done recently

Procedure

- Use SAG-M blood, which is the freshest available (to prolong its life in the patient)

- Red cells should be phenotype compatible i.e. ABO, Kell and Rh compatible (rr or Ro as appropriate)

- Do not use diuretics

- Continue to administer IV fluids at the standard rate between transfusions

- Critically ill patients may require exchanges to be more frequent than daily. Where possible, leave a 4 - 8 hour break between exchanges. In the very sick patient, the procedure is a continuous process. In these patients, particular attention should be paid to PaO2, CVP, acid-base balance, Ca++, citrate load, core temperature and clotting.

Automated Exchange Transfusion:

A national SNBTS SOP for automated red cell exchange exists and is available through SNBTS.

Information required

- Patient height and weight

- Pre-exchange Hb, Hct and HbS%

- Transfusion fluid Hct (or default 60%)

- Target values post red cell exchange

- Hb 100g/l

- Hct 0.35

- HbS 15%

- FCR – fraction of red cells remaining – can be calculated on apheresis instrument from pre and target post HbS %

Adequate venous access is required. If it is anticipated that adequate access may not be obtained via peripheral access then insertion of a large bore double lumen catheter with staggered ends should be arranged.

Manual Exchange Transfusion:

Volumes Required

The initial aim is to exchange 1.5 - 2 times the child's blood volume, divided over 2-3 procedures. 28ml/kg is the approximate red cell mass from infancy to teenage years

Volume (ml) of SAG-M blood for each exchange should be:

28 x weight (in kg) = volume in mls

Venous Access

Two ports of venous access are required; one for venesection, the other for administering blood and crystalloid;

Procedure

The aim is that this should be an isovolaemic procedure with frequent, monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturations every 15 minutes, and 1 hourly temperature monitoring. Exchanges are done in ‘aliquots’ of approximately 1/10 of the total to be exchanged.

- If Hb >60g/L start by giving a bolus of 10ml/kg of 0.9%saline. If Hb < 60g/l, start by transfusing 5ml/Kg of red cells then proceed to venesection.

- Venesect an aliquot (i.e. 10% of total volume to be exchanged) over 10- 15 minutes

- Transfuse an equal first aliquot at a rate of 5-7.5ml/kg/hr

- Venesect second aliquot

- Transfuse the second aliquot

- Venesect third aliquot, and so on

- Finish the procedure by giving the last aliquot of blood as a top-up transfusion ie venesect the 9th aliquot then transfuse 9th and 10th aliquots

At end of procedure check FBC, HbS %, urea and electrolytes including calcium. If HbS not <20%, then consider continuing with further exchanges, to give a final Hb of 110g/l and Hb S ideally between 10% and 20%.

Ensure the child is well hydrated between successive exchanges as the haematocrit of transfused packed cells is higher than that of the venesected blood.

Keep PCV<0.4. In larger volume exchanges consider giving a break between 2nd or 3rd unit and giving dextrose/saline to rehydrate.

Possible Immediate Complications

- Transfusion reactions - ABO incompatibility, febrile non-haemolytic reactions, TRALI etc

- Metabolic disturbances are rare, occurring usually in small children, or in association with visceral sequestration requiring continuous exchange

- Convulsions are very rare. They are usually a sign of cerebral sludging, often in patients with previous CNS problems. Check that the PCV has not risen too high (>0.4). Give anti-epileptics; ensure there is a large fluid intake; give oxygen.

- Hypertension is occasionally seen in patients with circulatory overload. If diastolic BP increases by > 20mmHg, slow down exchange, check PCV not >0.4. If diastolic BP is >100mmHg stop the exchange, venesect, and consider antihypertensives.

Sickle cell – chronic transfusion:

Aims

- Aim to achieve HbS <30% and suppress erythropoiesis

- Aim for Hb <110g/l post transfusion

- Transfusions of 10-20ml/kg are given 3-4 weekly to achieve the above targets and should be prescribed based on pre-transfusion Hb

- Patients should not wait longer than 1 hour for venepuncture, cannulation or transfusion and no more than 3 attempts at cannulation are recommended

Investigations

- Weekly

- FBC if on deferiprone

- Monthly

- Pre-transfusion FBC and HbS%

- Cross match for RCC

- U&E and creatinine (weekly for first 4 weeks on deferasirox)

- LFT, Ferritin

- Urine protein: Creatinine ratio if on deferasirox

Record results and transfusion volume (see Appendix 2)

- 3 monthly

- Above +

- Height and weight, record centiles

- Random blood glucose (further investigation if abnormal)

- Ca, Mg, PO4, Zinc

- Review of chelation therapy

- Annually

- Total transfusion requirement (ml/kg RCC transfused, mid-year weight)

- Annually from 4-8 years (when tolerated without GA)

- Liver MRI, Cardiac MRI

- Audiology and Ophthalmology on chelation

Annually from 10 years (or earlier if clinical concerns):

- Pubertal assessment, TFTs, sex hormones

- ECHO

- DEXA scan (2 yearly)

Consult Trust Transfusions Policy [Staffnet link]

It is important to educate the patient and family about the potential complications of iron overload and the need for chelation therapy and monitoring. Patients and other family members should be encouraged to be involved in the self-administration of medications at home.

When to start:

For those on regular top-up transfusions with a rising ferritin chelation should commence when the ferritin reaches 1000mcg/l, usually after 10-20 transfusions. Ferritin is an acute phase reactant and should be elevated on 2 occasions when the patient is well.

What to start:

| Age | 1st line | 2nd line |

| <2 years | Desferrioxamine | Deferasirox |

| 2-6 years | Desferrioxamine OR Deferasirox | |

| >6 years | Deferasirox OR Desferrioxamine | Deferiprone |

Chelators, dose, toxicities and drug safety monitoring - for full list of side effects and dosing consult BNF and SPC.

|

Desferrioxamine |

|

|

Dose range |

20-30mg/kg/day for 8-12 hours 5-7 d/wk |

|

Side effects |

Ototoxicity Lens opacities Yersinia infection - abdominal pain and fever Growth impairment |

|

Safety monitoring |

Annual audiometry Annual ophthalmology Stop drug and admit for investigation and treatment if patient develops diarrhea (consider Yersinia) Sitting and standing height |

|

Deferiprone |

|

|

Dose range |

75mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses, may increase to 100mg/kg/d |

|

Side effects |

Neutropenia and agranulocytosis (2%) GI upset, transaminitis Joint pains |

|

Safety monitoring |

Weekly FBC Patient advice re fever Monthly LFTs |

|

Deferasirox |

|

|

Dose range |

Film coated tablets: 7 – 28 mg/kg. Starting dose usually 14mgs/kg escalating in 3.5 – 7 mgs/kg increments (max dose: 28mgs/Kg) |

|

Side effects |

GI upset Transaminitis Reversible increase in creatinine, protinuria Rash |

|

Safety monitoring |

Creatinine monthly (weekly 1st 4 weeks) Urine protein creatinine ratio (monthly) LFTs monthly (weekly 1st 4 weeks) |

Drug and Dose adjustment: