Developmental care guideline

exp date isn't null, but text field is

Scope

To provide clinical guidance which supports consistent delivery of Family Centred Developmental Care practices across the Network. It includes the primary principles involved in Developmental Care and supporting the developing brain.

Audience

This guideline is applicable to all staff involved in the care of neonates and infants in West of Scotland Neonatal Units and on Paediatric Wards.

Developmental guidelines follow age-appropriate care strategies to support infants born sick, preterm, with congenital anomalies, or those who require surgical intervention and support their family throughout their hospitalisation in the neonatal care unit.

Infants of all gestational ages who require hospitalisation are vulnerable to traumatic experiences associated with hospitalisation and life-threatening illness; these include stress, parental separation and pain and have cumulative effect on the short term and long-term health and well-being of the infant and family 1, 2

Emerging evidence suggests that early life events are increasingly being recognised as influential in later physical and mental health outcomes 4

Supporting the physiologic, neuro-behavioural, and psycho-emotional needs of the hospitalised infant improves neuro-developmental outcomes and reduces their risk of adverse health outcomes across their lifespan 3

Creating a healing environment that buffers stress and pain while offering a calming and soothing approach to help keep the whole family involved in the infant’s care and development is an important factor in the overall aim of reducing morbidity and mortality rates 5

Developmentally supportive care has shown to be associated with:

|

The goals of developmental care for the infant are to:

|

The goals of developmental care for the family are to:

|

The care interventions/recommendations presented in this guideline are not intended to be prescriptive, but to support health care professionals deliver individualised age-appropriate developmental care within their own area of practice.

Neonatal caregivers should seek further specialist support from the multidisciplinary team if required.

Developmental care creates an environment that minimises stress while providing a developmentally appropriate nurturing setting for the infant and their family.

Due to the nature of the NICU environment infants are subjected to sensory overload and invasive procedures which are detrimental to the developing brain.

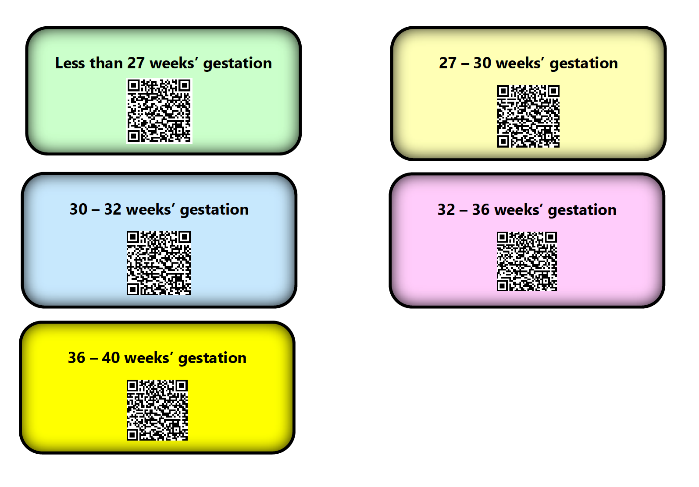

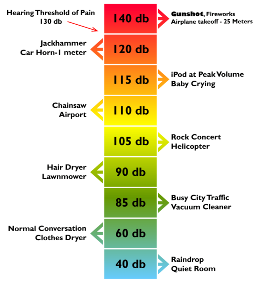

Hearing and Noise Levels

Loud noise may cause stress resulting in physiological changes such as increased heart rate, fluctuations in blood pressure along with decreasing oxygen saturations and sleep disturbance 8

The auditory system becomes functional at around 25 weeks' gestation. The cochlea and the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe are most important in the development of the auditory system. They are both easily affected by the environment and care practices in the newborn intensive care unit (NICU).

The British Safety Standards of noise within an incubator recommend a maximum of 65dB but The American Academy of Paediatrics suggests below 45dB as a safety threshold. 10, 11 Above 90dB for over 8 hours has the potential to damage the adult cochlea therefore the more immature cochlea is more sensitive to damage 12

Research has shown noise in the neonatal unit and inside the incubator can exceed 120bB 14 which is exceeding the maximum recommendation; this can be dependent on respiratory support such as Vapotherm, CPAP or Ventilation.

Ototoxic drugs can increase an infant’s sensitivity to noise due to the effect on the nerve supply such as diuretics and some antibiotics 13 However, we cannot avoid their use but should be aiming to stop antibiotics when infection is ruled out or the baby is responding to treatment.

It is crucial for staff to be proactive in reducing sound levels within the recommended guidelines.

Some units may find the use of a sound EAR helpful to highlight the current noise levels. However, general noise levels can also be acknowledged below.

|

|

- Silence alarms as soon as practicable and set alarms at lowest safe level

- Close incubator doors and drawers softly and do not place items on top of incubators

- Use Double walled incubators where possible

- Don’t tap on the incubators

- Remove excess water from any respiratory support system

- Aim to have conversations away from the incubator where possible

- Avoid speaking over incubators such as updating parents, ward rounds and handovers

- Bin lids should Be closed quietly

- Radios should not be allowed in the clinical area

- Phones to be placed as far away as possible from infants’ incubators. Use low output and to be answered promptly where possible

- Use of musical toys appropriate to gestation and infant state (not recommended before term gestation)

- Parents should be supported and encouraged to talk and read to their infant during awake and alert times

Vision and Lighting Levels

The newborn infant’s visual system is not fully developed at birth. Constant light disturbs diurnal rhythms.

The pupillary reflex is not fully developed before 32 weeks’ gestation. The eyelid is very thin therefore more light can enter the eye even when the eye lids are closed 15

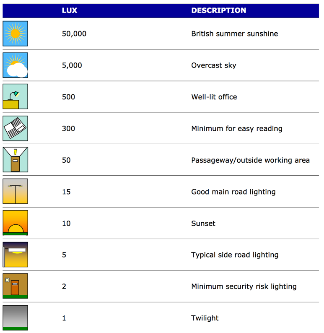

Light intensity is measured in Lux, which measures the perceived intensity of light. Both artificial and natural light play several roles in the neonatal environment: it supports the visual function of staff, affects the infant’s physiology and development, and regulates circadian function 15, 16, 17

Cycled lighting does appear to induce patterns of rest and activity and it may improve the infant’s ability to preserve circadian rhythms 18 Dim lighting has been reported to improve sleep, decrease motor activity, decrease heart rate, improve the feeding experience of the infant and increase weight gain. It has also been noted that when light levels in NICU are reduced, the actual frequency and duration of non-urgent care-giving activities by staff are also reduced 19

Ambient lighting can vary from 10-600 lux.

- Take the opportunity to ‘dim’ lighting whenever possible

- Use Incubator Covers for 23-32 weeks gestational age

- Avoid direct light into the infant’s eyes at all times

- Use opaque blinds

- Aim to protect the eyes post ROP screening for 6 hours post procedure (phototherapy eye masks can be used)

- Shield the infant’s eyes during any procedures that require overhead lighting

- From 32 weeks’ gestation introduce a cycle such as Daytime 100-200 lux and natural light if possible, at Night aim for <50 lux 17

- Use focused lighting such as an angle poise lamp at workstations to allow staff to do paperwork

Smell and Taste

Smell and Taste are closely interlinked, and one system will not fully function without the other.

The senses of smell and taste develop together in utero. The structures for tasting are present in utero from about 14 week’s gestation. The developing sense organs are bathed in amniotic fluid which has a chemosensory profile specific to each pregnancy. The mother’s diet has a particular influence on this profile 35

The baby is born able to recognise the particular profile in which his/her chemoreceptive system matured. Even preterm babies from 28 weeks’ gestation, have memorised their own amniotic profile and display the ability to recognise it in the presence of a competing amniotic smell 36

Babies have a preference to sweet tastes 37 and mother’s smell activates pre-feeding behaviours and influences state of arousal.

Providing exposure to the smell of breast milk and formula during tube feeding is a way of enriching the feeding experience through the olfactory sense 77

How as health professionals can we help?

|

Miniboos

The Miniboo is a comforter being used throughout the UK. It was created to bring comfort, contentment and reassurance to babies, by stimulating the baby’s awareness of their parent’s unique scent 38

To scent a Miniboo it should be placed against the skin of the parents, then placed in their baby’s incubator, close to the baby then swapped over at regular intervals. When placed with the infant this can soothe, calm and comfort them.

The benefits of using Miniboos

|

Miniboo is machine washable and retains its softness after washing 38

Non-Nutritive Sucking

Non-Nutritive Sucking (NNS) is a developmentally supportive intervention in response to the behavioural cues of the infant when bottle or breast-feeding opportunities are not available 39

The instigation of non-nutritive sucking is simple and effective and has been proven to have significant benefits to infants who have missed the opportunity to have any oral feeds due to being sick, preterm, requiring surgery or have other congenital abnormalities.

Infants born preterm can suck intermittently on a pacifier as early as 27-28 weeks’ gestation. It can also be achieved by encouraging the infant to suck on his/her hand, by providing mouth care, or if possible, an expressed breast 40

If mum is intending to breast feed, the baby should be allowed to lick/nuzzle, on an expressed breast during skin to skin prior to being mature enough to have a breastfeed. At the point where baby is transitioning to Breastfeeding NNS using a pacifier should be stopped.

Additionally, NNS helps facilitate the digestion of enteral feeds as stimulation of vagal mechanisms and stimulation of nerve fibres in the oral cavity, increases levels of gastrin and somatostatin, which aid acid secretion, gastric motility and the growth of intestinal mucosa 41

|

|

Kangaroo Care

Skin to skin contact (kangaroo care) has many benefits to both the baby and their family. It helps improve the baby’s respiratory rate, heart rate and oxygenation as well as maintain thermoregulation. When spending time in skin contact it promotes deep sleep and growth. Being close to their parent also provides comfort and induces calmness for both. The reassurance of parental touch together with a familiar smell and voice helps soothe the infant.

For mothers it is known to increase milk production and enhance parental emotional and psychological wellness.

Skin to skin should be initiated as soon as possible ideally in labour ward even if the opportunity is very brief.

It should be part of routine care offered to families every day for extended spells knowing that the benefits are dose dependant. Even infants who have complex needs including respiratory support should be offered KC where appropriate.

|

|

Benefits of Skin to skin or Kangaroo Care

- Helps to regulate baby’s temperature, heart rate, breathing and oxygen saturation and is associated with fewer episodes of apnoea and bradycardia

- Analgesic effect

- Increases time spent in quiet sleep

- Improved breastfeeding success and longer breastfeeding duration by supporting parents to recognise and respond to feeding cues as well as allowing the infant to practice instinctive feeding behaviours

- Faster growth rates 54 and earlier discharge from hospital

- Positive effect on parenting – reduces stress, triggers healing process and increases confidence

- Positive interactions with fathers during KC

- Recovery from birth-related fatigue for the mother 55

- Longer alert states and less crying at six months 78

- Promotes family centred care

After Discussion with the Medical Team

- Infants with Chest drains in situ

- Infants who are being actively cooled

- After surgery or major treatment – discuss with surgical team when it would be appropriate, NPASS scoring can assist with the decision

- ECLS(ECMO)

- Inotrope infusions – discuss on the ward round or with the duty consultant

- Infants requiring CFAM – discuss on the ward round or with the duty consultant

- Concerns regarding stability - discuss with a senior member of the medical team

- Previous unplanned extubation or an infant who has been a difficult intubation – make sure the duty consultant is aware

- Ensure within reach of a Neopuff and suction.

- Staffing numbers must be considered before offering KC for ventilated infants – should only be offered when there is sufficient nursing staff available, to support the safe transfer of the infant out of and into its incubator/cot. One person must be dedicated to holding the ET tube during the transfer.

- If staff are not familiar or confident to transfer an infant out for KC, seek support from an experienced staff member of staff.

- Umbilical lines arterial or venous are not a contraindication but need to be firmly secured.

- Offer a privacy screen and comfortable chair

- In partnership with parents plan for a suitable time and suggest that they parent to go to the toilet, have a drink or express first and wash their hands

- A loose-fitting top or buttoned shirt with an opening front is recommended ideally without a bra on for mum to maximise skin contact/access to the breast

- Ensure the infant has had any appropriate cares done prior to coming out of their incubator i.e. a temperature check and suctioning – allowing time for recovery before transfer commences.

- The infant should only wear a nappy.

- Disconnect any equipment not required for the transfer such as temperature cables, ECG leads can stay attached but can be disconnected whilst moving.

- Keep a saturation probe connected at all times.

- Check that the ET tube, CPAP mask/prongs or any nasal prongs are secured well before moving the infant.

- Ensure any lines such as PVCs, PICCs or Umbilical lines are also secured well.

Teaching video available - https://vimeo.com/522477070

Teaching video available - https://vimeo.com/522477070

The most stressful part of kangaroo care for the infant and their parents is the transfer in and out of the incubator/cot. Standing parent transfer decreases this and supports safer transfer for sicker infants.

Before any interaction it is important to talk to the baby to reassure them and let them know what is about to happen. Throughout the whole process maintaining a flex contained position, touch and the calming voice of the parent reassures the baby and reduces stress.

- When you are getting ready to move the infant make sure all lines and respiratory support are free to move and have enough give to reach the chair without stretching or dislodging them.

- Ensure infant is in a flexed midline position by gently swaddling in the sheet they are already lying on to minimise handling. This will allow uninterrupted skin contact once the infant has been lifted out of the incubator. Make sure infant’s feet are free of the blanket which means as soon as the baby is turned round its feet will be touching the parent’s tummy.

- The parent should stand at the incubator/cot side, place their forearm gently under the blanket, cup the head with the other hand, gently rotate their infant round lift the infant out of the incubator/cot resting the infant’s head against their sternum. The parent should continue to support the infant’s back and bottom with their forearm.

- The infants head should be placed to one side.

- The nurse should assist with any equipment i.e respiratory support, lines and monitoring.

- The parent sits back in the chair, guided by the nurse.

- The nurse should check that the infant’s legs are in flexion, head turned to the side to protect the airway.

- The nurse should check again that respiratory support is secure now that the parent is in a sitting position.

- Once comfortable on their parent’s chest, plug in all monitoring that was disconnected for transfer.

- Ensure the infant is not lying on any lines or wires and that any respiratory support is secured – Velcro adjusters can be used and attached to parents clothing.

- Check that the head of the infant is well supported and that you can see the infant easily.

- Place an extra blanket for warmth over the infant and parent if required.

- Offer a pillow for extra support.

- The longer the infant is out for kangaroo care the better. To maximise the benefits it should be at least an hour to mitigate for the stress response to transfer in and out of the incubator/cot.

- Kangaroo care allows the opportunity for the infant to develop their feeding behaviours and for parents to recognise their infant’s cues. Mum can express some milk onto her nipple. This will encourage her baby to lick and nuzzle at the breast.

- It is important to encourage parents to alternate the infants head position whilst having Kangaroo Care.

Nurse Transfer (second nurse required)

This method can be used for mums who are post c-section and unable or uncomfortable to stand and lift their infant. It may also be helpful for parents who are initially anxious to lift/touch their infant until they become more comfortable to participate in a parent transfer.

- Get the parent into a comfortable chair that reclines back, ensure clothing is opened and ready to receive the infant

- Wash hands.

- Contain the infant’s limbs and move gently.

- A second nurse is required to support ET tube, ventilator, CPAP, lines and wires.

- Gently place the infant on parent’s chest, prone with head to the parent’s sternum and with its head to one side to protect the airway.

- Ask the parent to support the infants head and body with their legs flexed.

- Once comfortable on their parents’ chest, plug in all monitoring that was disconnected for transfer.

- Ensure the infant is not lying on any lines or wires and that any respiratory support is secured – Velcro adjusters can be used and attached to parents clothing.

- Check that the head of the infant is well supported and that you can see the infant easily.

- Place an extra blanket for warmth over the infant and parent if required.

- Offer a pillow for extra support.

- Kangaroo care allows the opportunity for infant to develop feeding behaviours and for parents to learn baby cues. Mum can express some milk onto her nipple. This will encourage her baby to lick and nuzzle at the breast.

- Kangaroo care allows the opportunity for the infant to develop their feeding behaviours and for parents to recognise their infant’s cues. Mum can express some milk onto her nipple. This will encourage her baby to lick and nuzzle at the breast.

- It is important to encourage parents to alternate the infants head position whilst having Kangaroo Care.

Ideally KC should continue for as long as both parent and infant are comfortable. However, if the infant is showing any of the following signs, consideration should be given to the ongoing benefit:

- Increased oxygen requirement of 20% (e.g., from 30% to 50%) after being allowed a period of time to settle

- Infants showing signs of distress i.e., apnoeic, bradycardic, desaturation, colour change

- Hypothermia - < 36.5

- Infant remains unsettled or distressed after being given an appropriate period of time to settle

Generally, infants having skin to skin are more stable than infants in an incubator or cot. It is encouraged that if the infant is unsettled try changing the infant’s position slightly, ensure they are not lying on any wires/lines, try a little breastmilk on their lips. If the infant remains unsettled, then they may need to go back into their incubator/cot.

It is acceptable to give an infant NG/NJ feed whilst they are in the Kangaroo Care position. This should be encouraged to facilitate extended periods of skin to skin.

Therapeutic postural support and handling

Sensory motor development and postural control have been demonstrated to be critical for the short and long term neurodevelopmental and cognitive outcomes of NICU survivors 32

Muscle tone develops in a caudal cephalic direction and the fluid-filled uterus unaffected by gravity is the optimal environment to support this development. However, infants born preterm and sick term infants can be compromised by the forces of gravity that can impact spontaneous movement and ongoing musculoskeletal development 56

Ensuring appropriate postural alignment for comfort not only influences neuromotor and sensory development but also impacts on physiological function and stability, skin integrity, thermal regulation, bone density, sleep facilitation and brain development 57

Preterm and sick term infants left in unsupported, extended positions frequently exhibit increased stress and agitation with decreased physiologic stability 58 Side lying decreases the effects of gravity and facilitates midline orientation of head and extremities. It is the position that best encourages hand to hand, hand to mouth/face activity and is therefore the position that provides the best developmental advantages 58

Positioning should not compromise an infant’s medical care or stability.

Proprioception:

The sense Proprioception is that of body position, location, orientation, and movement.

The information is received through receptors in muscles and joints – for example force, speed, and control, about how and where we are moving in the space around us. This is basically where each part of our body is in relation to others, and how much effort is required from each of the parts to get the desired movement. This can affect how we drink from a cup with control, throw a ball to hit a target, how to move our body to fit through a small space.

Vestibular:

The vestibular sense is our sense of movement and balance.

Along with the cochlea of the auditory system, it comprises the labyrinth of the inner ear. Movement of the fluids in these semi-circular canals inform us of changes in our head position, gravitational pull, and direction and speed of movement. The vestibular system signals to our other senses when it’s necessary to make adjustments so that we can maintain balance, clear vision, adequate muscle tone, and coordination.

Dysfunction can present as hypo or hyper responsive. Like other senses you can have a mixture of both. Some infants might be movement seekers and like to be rocking or on the go. They have poor balance and posture, as Our vestibular system helps us to control our ‘postural tone, If our postural tone is too high we might find it difficult to change positions smoothly and grade our movements, The vestibular system tells us where our body is in relation to gravity- This might present with excessive fear of falling, avoiding uneven surfaces.

Benefits of positioning for infants:

|

Infant’s positioning is generally a nursing intervention which can improve patient outcomes. However, it should be everyone’s job and it can be taught to parents.

|

Positioning equipment

There are a number of commercially available positioning aids and postural supports however understanding the rationale for providing postural support is vital to ensure appropriate choice and use to enhance developmental outcomes. Incorrect and inappropriate usage may result in negative consequences.

It is important that staff looking after infants within NICU understand the principles of providing postural support, however this needs to be individualised depending on the clinical needs.

Neonatal units and Paediatric Wards have access to a range of Allied Health Professionals (AHP). All staff working in NICU should have training on the use of postural supports and staff should seek support for more complex positioning advice from appropriate AHP.

Below as some examples of good practice using a variety of commercially available products as well as examples of use of soft rolls for some of the older neonates.

Examples of correct positioning for infants –

LEFT PRONE |

LEFT SIDE LYING |

SUPINE (RIGHT) |

RIGHT PRONE |

RIGHT SIDE LYING |

SUPINE (LEFT) |

LEFT SIDE LYING |

SUPINE (MIDLINE) |

RIGHT SIDE LYING |

In line with individualised care, experience would lead us to encourage postural support for preterm infants until they are established on oral feeds (feeding develops in line with Physiological flexion and sensory-motor development) in preparation for back to sleep for going home.

If infants require postural supports for longer or for other reasons, then they require individual assessment by Physio/OT/SALT.

Therapeutic positioning in the Neonatal Unit

video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQwDUVJwiUM

video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQwDUVJwiUM

Whilst no evidence-based guidance currently exists for the ‘ideal’ surface to nurse an infant on it is clear that surface firmness will have an effect on cranial moulding and tissue compromise.

It seems sensible to consider nursing the most vulnerable infant on the softer more gently supportive surfaces, if available.

For example, babies less than 28 weeks’ gestation, babies with reduced mobility (due to being critically ill, muscular conditions, muscle relaxants), babies with skin integrity problems or with known surface: skin pressure vulnerabilities such as hydrocephalus or abnormal limbs/joints.

To ensure that the positioning aid meets the positioning needs of the baby –

|

Safe practice

|

Handling

Time repositioning or handling of an infant to coincide with their natural sleep/wake cycle. Whenever possible an infant should be touched gently before they receive any handling, allowing them time to become more wakeful before more handling occurs. This gives them an opportunity to self-regulate, and not to be ‘startled’ by a sudden position change or touch.

Position changes should be slow and steady, so the infant has time to adjust to care and is not distressed. This also ensures that invasive monitoring equipment is not dislodged.

When turning an infant try to use a palmar grip as opposed to fingertip pressure, reducing the risk of pressure damage to the fragile skin.

During handling and repositioning, the infant’s arms and legs should be kept close to their body. Non-nutritive sucking can be used to support infants during re-positioning.

An infant should never be rapidly ‘flipped over’ 180 degrees –known in the literature as the ‘preemie flip’. This sudden position change is likely to be distressing and destabilising.

All members of the multi-disciplinary team should remember to reposition an infant once they have completed a task, i.e. a blood test, examination or nursing care. If a staff member is uncertain how to do this, they should inform the infant’s allocated nurse, who will educate and support them.

Recent research has shown that babies nursed in neonatal units continue to receive excessive handling. In a typical 24-hour period found that babies on average received 67 procedures 60

Individualised assessment should take place, of the infant’s needs and preferences. Staff should where possible, be guided in the timing of handling the infant by their cues.

It can be helpful to cluster 1-2 activities together for an infant, to reduce the overall amount and frequency of handling that they receive. However, this should be limited to what the baby can tolerate, as extremely sick and/ or preterm babies will not cope with a number of activities being performed close together. All infants will need time to recover following procedures.

Post term babies

Infants who are post term and older, and still requiring care on a neonatal unit will begin to have additional positioning needs related to their physical, sensory, cognitive and commination development.

Older neonates who remain in a hospital environment should have an individualised assessment and management plan from appropriate Allied Health Professionals. The plan may recommend additional or alternative positions and postures to physical and sensory development, early interaction, communication, and seating to support an upright posture if appropriate. AHP’s work very closely with families and carers who are key to enhancing long term outcomes for high-risk infants.

Positioning for discharge

In preparation for discharge infants should sleep on their back ‘back to sleep’ without positioning aids and with the head of the bed in the flat position. Support can be removed gradually, but infants should have a minimum of have one week before discharge, and ideally two weeks, sleeping as they would at home. This helps to educate their parents and gives the infant time to adapt whilst still in hospital to the safest way of sleeping at home.

Actively involve parents in supportive positioning and explain the reasons for the importance of it.

- Educate parents on the differences in positioning between the neonatal unit and home. In particular after discharge, unless medically directed:

- No nesting or positioning roles to be used.

- No soft layers between the baby and the mattress- e.g., sheepskin or fleece. -Mattress to be level, head NOT elevated.

- Baby to be laid supine for sleeping.

- Emphasise cot death prevention guidelines including ‘feet to foot’ recommendation.

Infants who remain in our care beyond the neonatal stage would be considered as post term babies. At this point corrected gestational age should be used to ensure an appropriate developmental environment.

Early intervention and interaction can be tiring for infants who have been sick or born early. It is important to consider if infants are medically stable to engage in additional activities and handling. It is therefore important that this interaction takes place when the baby is awake and alert 88

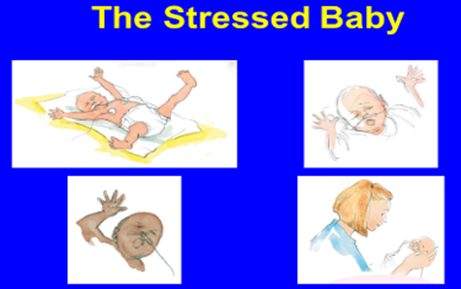

Infants must be carefully observed for any signs of stress or distress during interaction.

The full support of the multidisciplinary team is recommended to develop an individualised developmental care plan in partnership with parents who are central to their infant’s developmental health and wellbeing.

In the early stages of both preterm and post term, the aim is to develop their attachment and interaction with parents and family. This can be done through during normal care activities, bathing, feeding, parents reading and singing to their baby, and the use of voice and touch to interact with the baby during wakeful times.

Parents may not always be present when the baby is awake and alert for early interaction and play. In these incidences, where possible, staff should engage in the above activities providing consistency with the baby to promote development and wellbeing.

Developmental care is an early interventional approach to enhance the infant’s development, enhance parent- infant relationship, and reduce the risks of developing insecure attachment.

Caregivers should:

- understand the infant cues

- Work with the baby’s states of arousal

- Understand the parent-infant relationship and how to guide parents/carers to accurately observe, interpret and respond to their infant’s unique cues

Communication is a reciprocal activity; babies receive information through their senses.

Their behaviour is their language.

| Infants' cues: |  |

Signs of Stress include:

|

|

|

Stress response starts with Behavioural cues, if the infant not contained, physiological response with changes in heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation will follow, which will result in neurochemical response with increase release of stress hormones which can be harmful.

States of arousal:

There are six states of arousal and from 32 weeks’ gestation, babies can display organised sleep and arousal state and can maintain a quiet alert state for a short period (<32/40 most of their awake is a drowsy awake and their sleep is light sleep).

- Deep sleep

- Light sleep

- Drowsy

- Quiet alert

- Active alert

- Crying

The best time to interact with a baby or have an intervention is during quiet alert state.

1.  |

2.  |

3.  |

4.  |

5.  |

6.  |

Well organised sleep is associated with improved cognitive and psychomotor development as well as stress reduction, increased immune function, improved growth, stable oxygenation and autonomic stability 9, 56, 72

Rapid Eye Movement (REM - light sleep) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM - deep sleep) sleep cycles are essential for early neurosensory development, learning, memory and preservation of brain plasticity 1

REM is characterised by rapid eye movements under closed eyelids, periods of irregular and regular breathing, low level activity, occasional startles, whimpers, smiles, mouthing and sucking behaviours.

NREM is characterised by regular breathing, no rapid eye movements, relaxed facial expression, absence of spontaneous motor activity and occasional startles 1

Evidence suggests that preterm infants spend up to 80% of their time in REM reducing to 50% in REM by the time they reach term. It is therefore vital for all caregivers to recognise and respect REM sleep.

As health professionals how can we help:

|

Infants with prolonged stay in hospital are at risk of both over-stimulation and under-stimulation. It is important to promote positive relationship.

“Positive relationships promote good mental health” applies to both parent and infant.

Promoting Resilience:

- Create an environment that is enabling for baby to self-regulate (through developmental care)

- Enable parents to interact with baby and to understand their baby’s unique cues

- Be aware of parent’s mental state and discuss availability of professional help if required

- Promote mother’s perception as primary caretaker (‘Good enough’ mothering)

- Understand the Father’s mental health as he has lost his nurturing role, hence the father tends to focus on baby’s physical status, equipment and monitors.

- Understand the impact on siblings and try to create a family-friendly environment

Risks to Sensory Development:

- High noise levels

- Lack of pleasant touch

- Lack of pleasant smells

- Intrusive light levels

- Lack of visual stimulation

- Lack of light/dark cycle

- Interrupted sleep

- Lack of appropriate postural support

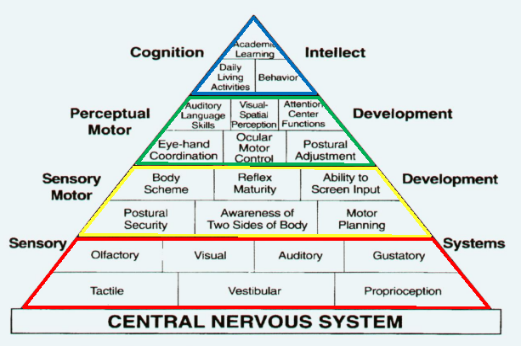

Importance of age-appropriate sensory stimulation /processing and potential long-term impact on the child

Long-term risks of dysregulation (‘Sensory processing disorder’):

- Difficulty forming attachment

- Feeding and nutritional problems

- Delayed play skills

- Aggressive outbursts/withdrawn

- Sleep deprivation

- Delayed motor development

Impact on Learning:

The pyramid of learning is a visual illustration to help understanding how the sensory systems are truly the foundation for many other areas of development. Children’s bodies need a strong foundation of nourishment for the central nervous system.

How can we help protect infants from sensory dysregulation?

|

References for Understanding Infants Behaviour - 20-34

Infants exposed to adverse stressful experiences can result in long-term behavioural outcomes. Developmental care practices can be used to minimise the effects pain can cause along with the relief of discomfort 83

Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual and potential tissue damage 67

Neonates cannot verbally communicate their discomfort; however, evidence suggests that neonates do experience pain but lack the adaptive mechanisms that modulate painful stimuli in older children. They express their vulnerability to pain and stress through specific behaviours and with physiological and biochemical responses to pain 68

Neonates are frequently exposed to acute, repetitive, and chronic pain within the NICU setting because of procedures, surgeries, and disease processes. Preterm neonates, especially those <30 weeks’ gestation, can be exposed to up to 10-15 painful procedures per day 69

How we can minimise pain

It is important to consider each procedure/event and avoid or limit where possible. Reducing Noise and Light within the environment also reduce pain caused by stress.

Limitation or avoidance of skin-breaking or other painful procedures

|

Use Pain Relieving Interventions (pharmacological and non-pharmacological)

|

Starting doses for each medication are as per the MCN for West of Scotland Guideline, but dosing and weaning should be individualised.

For more Information refer to WOS Neonatal Pain Guideline

Facilitating tucking

A key concept of Best Start: A Five-Year Plan (2017) is optimising normal processes to strengthen women’s own parenting capabilities. During recent years there has been increased interest in parental participation in all aspects of neonatal care 56 The greatest source of stress that parents experience in the NICU comes from lacking a parental role and not being able to protect their baby from harm 81

Both staff and parents can promote behavioral state organization of sick and premature infants, with the effective use of facilitated tucking (holding the infant's extremities flexed and contained close to the trunk) during heel stick, cannulation and PICC line insertion resulting in lowered mean heart rate, less crying time and more stability in the sleep-wake cycles post procedure 80

The family is an integral part of supporting the infant’s development and irreplaceable 1 Admission to the neonatal unit can significantly influence the immediate and long-term mental health of their parents 70, 71

The family involvement is the key for potential long-lasting positive effects on development of all infants 73

Parents should be an essential member of the team and become a partnership in care.

How to assist families:

|

Care activities are best described as parenting activities which should validate the parental role identity, build competence and confidence and in turn reduce the infant’s and parent’s stress. The level of the family’s emotional well-being, parental confidence, and competence should be assessed and documented within the nursing notes. This will ensure consistency by all staff when working in partnership with the family. The family should have access to resources and support services that assist in short-term and long-term parenting, decision making, and parental well-being 74, 75, 76

When stress occurs early in life, there is potential significant risk for the experience to affect the child’s developmental trajectory. Research has demonstrated an association between the timing and chronicity of a highly stressful events during development with the risk for an adverse outcome 2 Furthermore, when children lack the presence of a stable and loving caregiver during times of stress exposure, the impact of the experience may be greater than it otherwise would be. This can be a common occurrence for hospitalised infants due to the intermittent presence of their parents, as parents juggle the needs of their home lives and their infant 2

Although developmental supportive care has been separated to aid clarity it is important to note that all elements are integral to the holistic care of the infant and family.

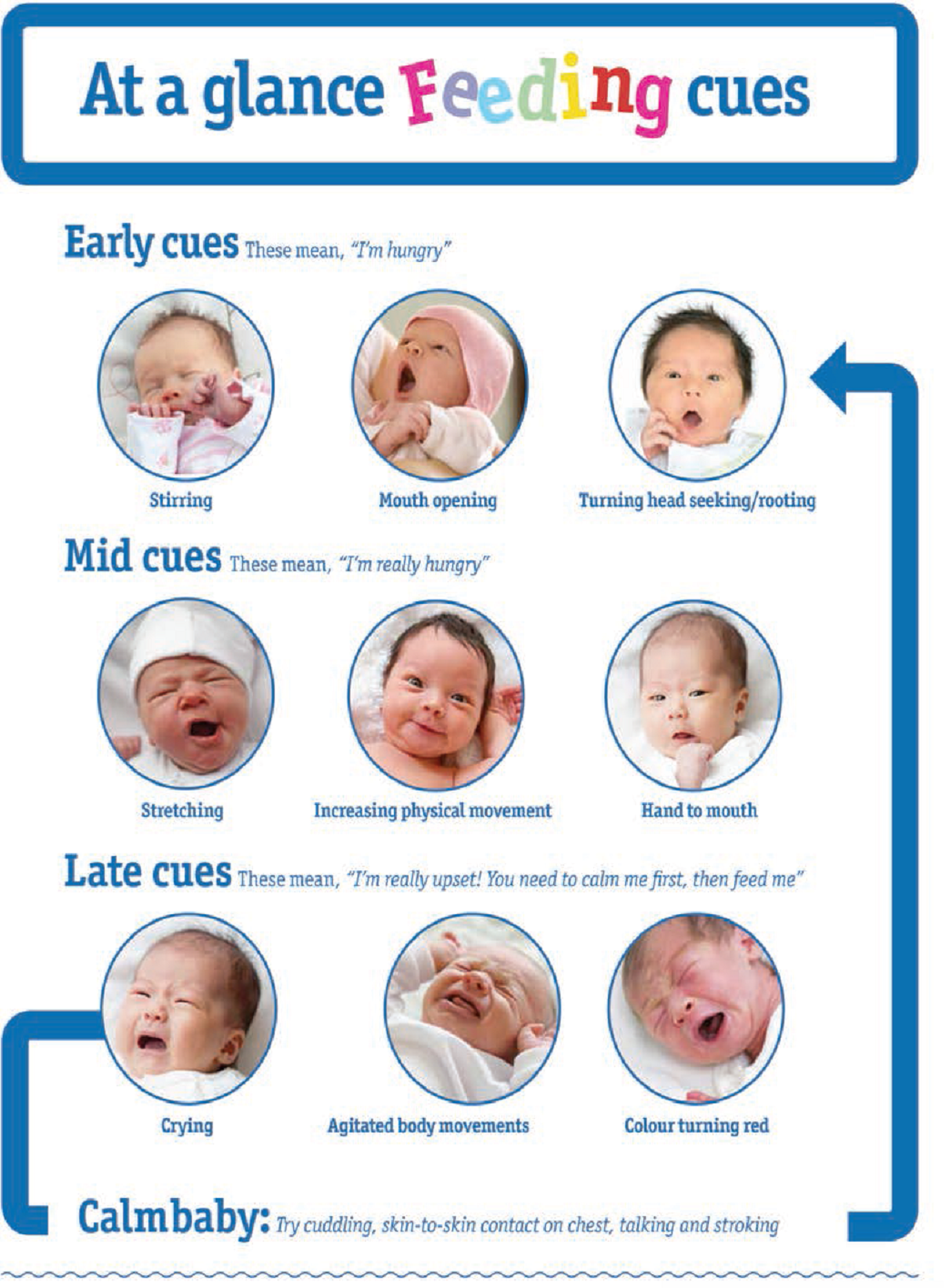

Cue based feeding is perceived as a meaningful behaviour where the focus changed from the medical approach of volume driven to an infant driven approach 51 The infant’s behaviour is the main driver for oral feeding. It requires staff to change their routine to respond to the feeding cues or stress cues of the infant 52

|

Traditional Volume Driven Model Volume intake is only measure of success |

Developmental Cue Based Model Infant’s cues drive feeding initiations and progression |

It involves a continuous assessment, decision and action based on the infant’s behaviour 53 Nutrition, gut health and weight gain are critical to address feeding in the NICU.

The medical approach volume driven feeding should be used until the infant begins to orally feed. Feeding is not a task of nutritional intake it has many social correlates not only in infancy but throughout life.

Benefits of Cue Based Feeding

|

It is important to learn how to assess, respond and optimally support infants as they learn this new skill.

Most literature supports offering oral feeds from 32 weeks’ gestation, according to readiness cues. But naturally there will be exceptions, breast feeding may be possible before this gestation.

Use of a systematic assessment tool, facilitates neonatal care units to develop a common language for feeding assessment and elevates understanding of the challenge of feeding for the preterm infant.

Principles of developmental supportive care are fundamental to the implementation of successful cue-based feeding practice –

- Documentation of oral feeding readiness and quality

- interventions of support are needed such as a slow or medium flow teat

- Position should also be considered to provide the infant support and optimise the postural stability and control such as side lying or supportive swaddling

- Provide the infant with external pacing during the feed

- Assess the infant’s behaviour from moment to moment

- Avoid in coordination of swallowing and breathing

Skilful feeding assessment streamlines the process of selecting effective interventions that address the needs of the infant and joint reflection encourages consistency of care between parents and staff.

The path to feeding success begins long before the introduction of oral feeds. Feeding safely and achieving adequate intake for growth require the dynamic integration, maturation, and coordination of multiple subsystems.

Feeding Readiness Cues

- Stable respiratory rate

- Maintain oxygen saturations during gentle handling

- Infant transitions readily to an alert state

- The infant is able to lick, nuzzle or suck non-nutritively on the breast or sustain non-nutritive sucking on a pacifier

- Roots in response to touch around the mouth

Feeding Readiness Scale

|

5 |

Alert or awake prior to feed. Rooting or turning head or mouth opening. Good flexed body posture. |

|

4 |

Infant becomes more alert with gentle handling. May show signs of rooting or turning head or mouth opening. Able to maintain good flexed body posture with supportive handling. |

|

3 |

Fluctuating state of alertness-unable to stay awake during cares. No signs of rooting. No sustained flexed body posture. |

|

2 |

Does not wake for feed and remains sleepy during handling. No feeding readiness cues. |

|

1 |

Unstable upon handling-changes in respiratory rate; heart rate and oxygen saturations during cares. |

Stress Cues and when to stop

- Crying; facial grimacing and irritability

- Pulling away, arching back and finger splaying

- Hiccups

- Vomiting

- Obvious fatigue

- Oxygen desaturations

- Any colour changes

If any stress signs are observed, offer a rest period.

If stress cues continue with further feeding attempts, then give the remainder via NG tube.

Cue based feeding is based on the quality of feeding rather than the volume.

Bathing a baby should be a special shared moment between parent and infant. Involving parents in providing care for their baby can help with attachment, increased confidence and interaction between parent and baby 61

It is widely accepted that bathing is a stressful experience for term infants therefore consideration should be given to its impact on vulnerable preterm infants.62 Initially, feeling wet may be a little uncomfortable however infants who feel safe and secure during the process should relax more 63

Supporting & handling a baby with gentle touch and containment during bathing should reduce signs & levels of stress 64

In addition to the stress experienced by the infant during bathing, the preterm infant especially is at risk of heat loss due to large body surface area in comparison to body mass, low brown fat stores and thinner skin. Hypothermia can lead to increased morbidity and mortality in the neonatal population. Therefore, reducing stress whilst maintaining body temperature are key components to be considered when bathing preterm infants 65

A method of bathing which is hypothesized to help maintain body temperature and reduce the stress associated with conventional bathing is swaddled bathing. Swaddled bathing involves placing the infant in a flexed midline position, swaddling in a soft towel, immersing in a tub of warm water, individually unswaddling each limb to be washed then reswaddling which maintains the midline flexed position throughout making it a developmentally supportive process.

Reported benefits include decreased stress; reduced crying; improved state control; increased self-regulatory behaviours; increased feelings of security; increased social interaction; and increased ability to feed following bathing 65

A quality improvement project carried out in the Neonatal Unit at University Hospital Wishaw concluded that when swaddle bathed, infants do not loose heat, cry less and the bathing experience appears less stressful and much more enjoyable for infants and their families. The primary principal of developmental care is to create the optimum environment whilst applying developmentally supportive strategies to reduce stress for neonates and their families 66

Swaddle bathing encourages family centred care and recognises parents as partners as the initial swaddle bath is demonstrated by staff with parental participation. Any subsequent swaddle baths can be performed by parents with staff support or independently when parents feel confident.

What you need to perform swaddle bath

|

|

When to perform swaddle bath

Aim to perform prior to a feed at a time when cluster care would ordinarily be given. If this is not possible wait at least one hour after their feed 61

Eligibility criteria for a swaddle bath:

- Babies of any weight/gestation can be included as long as they are deemed medically fit for bathing.

- Babies on respiratory support can be included.

- Babies nursed in incubators/babytherm/heated mattresses can be included.

Protocol for Swaddle Bathing:

- Fill bath with enough water to cover shoulders and use a thermometer to check the temperature is 37-38 degrees.

- It is optional to use soap. If parent wish they can add gentle bath soap to the water prior to the placing the baby in the bath.

- Show Parents how to provide support under the baby's shoulders/neck throughout the entire bath. Feet may be braced at the end of the tub for additional comfort of the baby.

- Note that the infant should not be in the water for more than 5-6 minutes approximately.

- Remove clothes and place baby on a muslin with the nappy still on.

- With a separate bowl of clean water clean the infant's face using a washcloth/gauze and no soap. Start with the eyes by gently wiping from nose to ears using a new washcloth or piece of gauze for each eye and then gently clean and dry around entire face. Keep bowl to use for hair washing at end.

- Remove nappy and clean napkin area as usual.

- Disconnect monitoring.

- Place baby still wrapped in the muslin in the tub. Provide support under the baby's shoulders and neck throughout the entire bath.

- Unwrap one of the infant's arms and wash gently including the chest then re swaddle with the muslin.

- Unwrap the other arm and wash gently including the chest then re swaddle with the muslin.

- Unwrap one leg including the stomach, wash gently then re swaddle with the muslin.

- Unwrap the other leg including the stomach then re swaddle with the muslin.

- The baby’s back is washed with the water through the muslin.

- End the bath with hair washing using separate bowl of clean water.

- Once bathing is complete, unwrap the baby from the muslin leaving the wet muslin in the bath.

- Place a dry towel up against the Nurse or parent’s chest. Remove baby from the tub and wrap in the towel.

Activities of Daily Living to Further Support Infants Development

- Each infant is positioned and handled in flexion, containment, and alignment during all caregiving activities

- Infant’s position is evaluated with every infant interaction and modified to support symmetric development

- Positioning aides are gradually removed and Back to Sleep practices are implemented as the infant demonstrates physiologic flexion of the upper body in supine

- Non-nutritive sucking is offered with each non-oral feeding contingent on the infant’s state

- Assessment of feeding readiness cues and the quality of the oral feeding is documented with each oral feeding encounter

- Education regarding the benefits of breastmilk is provided and family choice is supported

- Infants are bathed no more frequently than every 3 days

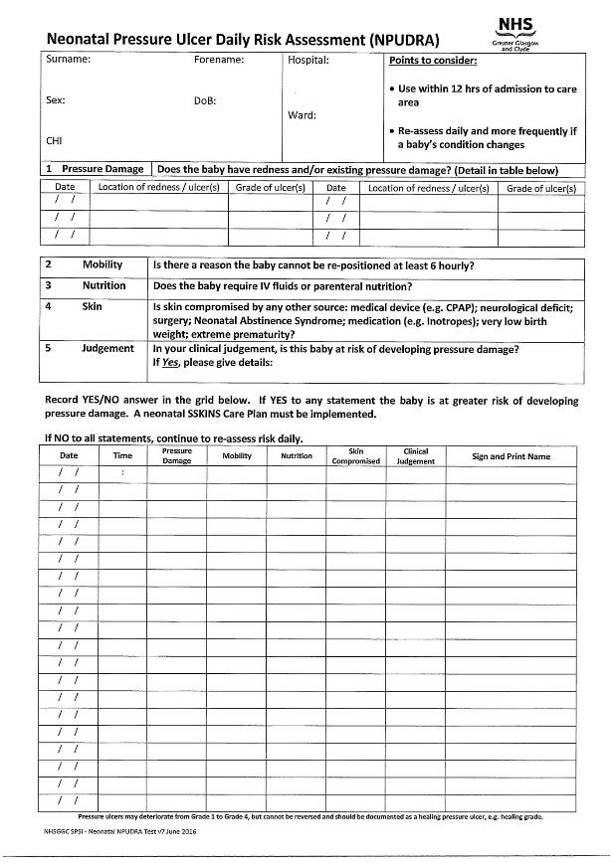

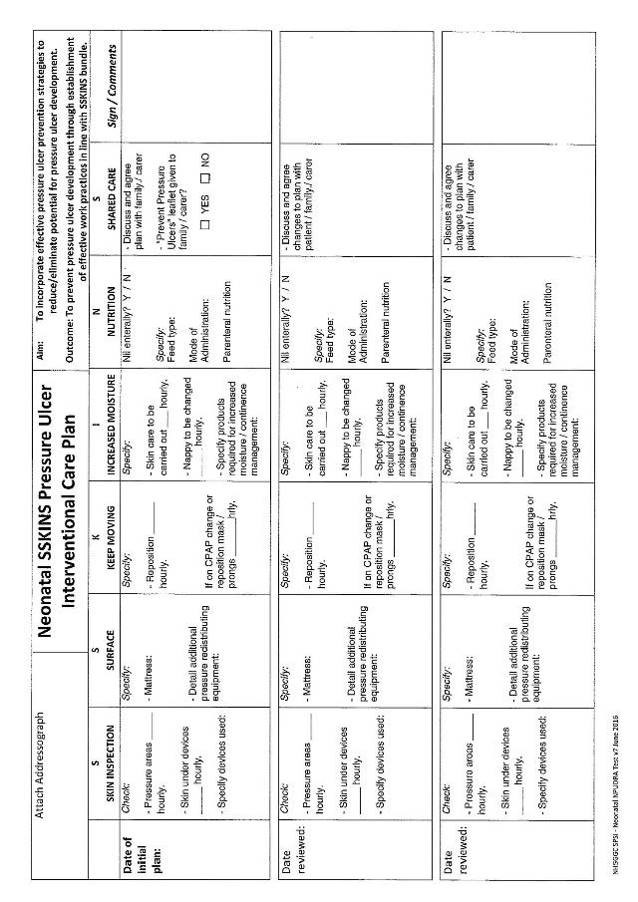

- Skin integrity is assessed using a reliable assessment tool at least once per shift and documented. (NPUDRA, appendix 2)

- The skin surface is protected during application, utilisation and removal of adhesive products

- Assess infant’s sleep-wake states prior to undertaking non-emergency care interventions, based on the infant’s state of arousal and behavioural cues.

|

|

24-27 weeks |

28-32 weeks |

33-36 weeks |

37 weeks plus |

|

Behavioural Development |

Behavioural states poorly differentiated Response to handling results in physiological instability Diffuse ranging signs of instability from typical stress signs to exhausted collapse |

Behavioural states more distinct by 32 weeks Quiet/deep sleep increases around 30 weeks Response to handling results in physiologic instability Shows more typical signs of stress |

Behavioural states more distinct Smoother transition between state Quiet/deep sleep continues to increase May arouse for feeding Stress response to noxious stimuli varies but physiological instability still evident

|

Behavioural states well defined with clear transitions Tolerance of handling and interventions usually increase Periods of alertness for socialisation with development of longer attention spans |

|

Motor Development |

Movements are mainly jerks, twitches and startles that can increase with stressful input Weak muscle tone. Decreased flexion in limbs, trunk and pelvis Unable to control posture, movement and tone

|

Twitches and startles common at 28 weeks leading to more controlled movements by 32 weeks. Muscle tone weak but develops slowly over this gestational period Leg movements increase with the start of flexion in the hips and legs

|

Smoother more controlled movements Stronger flexion of knees and hips during rest with further development of tone in the lower extremities Can turn own head side to side Has improved capability to use posture and movement to self-regulate

|

Demonstrates a wide range of movements Controlled movements increase Trunk and extremities usually flexed at rest Can self-regulate behaviour with movement and posture |

|

Light and Vision Development |

Eyelids may be fused at 23-25 weeks Cornea hazy until 27 weeks. Pupil reflex is absent Limited ability to maintain lid tightening in response to light Eyes may open but do not focus Responds to light/visual stimulus with behavioural and physiological signs of stress |

Sluggish pupil response to light Able to maintain lid tightening in response to bright light Eye opening increases in dim light May focus briefly on visual stimuli Rapid uncoordinated eye movements

|

Increased ability to maintain lid tightening in response to bright light Eye opening and alert state are facilitated by low lighting Infant may have difficulty breaking gaze on a highly stimulating object

|

Generally, shows preference for human face Sees best at a distance of 20 -25cm. Sight is still immature with much development to follow at 0-6months. |

|

Sound and Hearing Development |

Inner ear has attained full adult size and function Infant may respond to soft voice and sound and may show preference for mothers’ voice May demonstrate physiological instability to noise/auditory activity |

Middle ear and transmission section of auditory system is complete Orientation to soft sounds develop during this period Infant can quickly fatigue to auditory stimulation Infant is sensitive to loud noise and can demonstrate physiological instability to noise/auditory activity |

Sensory and transmission portions of the auditory system are functional Increasing responsiveness to voice stimuli with a preference for a soft human voice Responses to noise and auditory environments begin to organise Startle response with loud noise still evident

|

Response to noise is more consistent and organised Can localise and discriminate sounds Stress behaviours may still be displayed to certain loud sounds Gradual onset of auditory stimuli preferred. |

|

Non-nutritive Sucking Development |

Immature gastrointestinal system Gag reflex present at 26 weeks Sucking may appear but not synchronised to swallow |

Rooting reflex present but a delayed response can occur Poor suck, swallow and breathe coordination that matures over this period |

Suck, swallow and breathe co-ordination maturing with some rhythmicity but coordination can be inconsistent Rooting reflex emerges Can nuzzle at the breast

|

Suck, swallow and breathe coordination becomes more consistent and organised Endurance for oral feeding increases |

Acknowledgements to – East of England Neonatal ODN Clinical Guideline: Developmental Care, Southampton NICU Developmental Care Guideline and The Northern Neonatal Network

1 Coughlin, M. (2014). Transformative Nursing in the NICU: Trauma-Informed Age-Appropriate Care. New York: Springer Publishing.

2 D’Agata, A.L., Sanders, M.R., Grasso, D.J., Young, E.E., Cong, X. and Mcgrath, J.M. (2017). UNPACKING THE BURDEN OF CARE FOR INFANTS IN THE NICU. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(2), pp.306–317.

3 Johnson, S.B., Riley, A.W., Granger, D.A., & Riis, J. (2010). The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Paediatrics Vol 131. pp. 319-327.

4 Marcellus,L and Cross,S. (2016). Trauma-Informed Care in the NICU: Implications for Early Childhood Development. Neonatal Network. Vol 35(6). pp. 359-366.

5 Altimier, L., & Phillips, R. (2016). The Neonatal Integrative Developmental Care Model: Advanced Clinical Applications of the Seven Core Measures for Neuroprotective Family-centered Developmental Care. Newborn & Infant Nursing Reviews, 16(4), 230–244. https://doi-org.ezproxy.napier.ac.uk/10.1053/j.nainr.2016.09.030

6 Poppy Report, 2009 – Premature Babies project.

7 Pineda, R., Bender, J., Hall, B., Shabosky, L., Annecca, A. and Smith, J. (2018). Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: Predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental outcomes. Early Human Development, 117(18), pp.32–38.

8 Lahave, A. and Skoe, E. (2014) An acoustic gap between the NICU and womb: a potential risk for compromised neuroplasticity of the auditory system in preterm infants. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Vol 8, pp.381.

9 Graven, S, N. and Browne.J. V (2008) Auditory Development in the foetus and infant. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, Vol. 8(4), pp.187-193.

10 Austin, T. and Edwards, A. (2016). Noise in the NICU: how prevalent is it and is it a problem? Noise in the NICU: how prevalent is it and is it a problem?, [online] 12(5). Available at: Noise in the NICU: how prevalent is it and is it a problem?.

11 Almadhoob, A. and Olhsson, A. (2015) Sound reduction management in the neonatal intensive care unit for preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Systematic Reivews. Available: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010333.pub2

12 WHO https://www.who.int/ceh/capacity/noise.pdf

13 Garinis, A, C., Kemph, A., Tharpe, A, M., Weitkamp, J., McEvoy, C. and Steyger. P, S. (2018) Monitoring Neonates for Ototoxicity. International Journal of Audiology. Vol 57(4), pp. 41-48.

14 Ranganna, R. and Bustani, P. (2011) Reducing noise on the neonatal unit, Infant Joural. Vol 7(1), pp. 25-18.

15 Rodriguez, R.G. & Pattini, A.E. (2016). Neonatal intensive care unit lighting: update and recommendations. Archivos Argentinos de Pediatria, Vol.114 (4), pp.361-367.

16 White, A. and Parnell, K. (2013) The transition from tube to full oral feeding (breast or bottle) – A cue-based developmental approach. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. Vol.19 (4), pp.189-197.

17 Graven, S. (2011) Early visual development: implications for the neonatal intensive care unit and care. Clinics in Perinatology, Vol.38 (4) pp.671-683.

18 Mirmiran, M. and Ariagno, R.L. (2000). Influence of light in the NICU on the development of circadian rhythms in preterm infants. Seminars in Perinatology, [online] 24(4), pp.247–257. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0146000500800361?via%3Dihub [Accessed 12 Mar. 2021].

19 Figueiro, M.G., Appleman, K., Bullough, J.D. and Rea, M.S. (2006). A discussion of recommended standards for lighting in the newborn intensive care unit. Journal of Perinatology, [online] 26(3), pp.S19–S26. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/7211586#article-info [Accessed 12 Mar. 2021].

20 Olena Chorna, Jessica E Solomon, James C Slaughter et al.Abnormal sensory reactivity in preterm infants during the first year correlates with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years of age. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014 November ; 99(6): F475–F479

21 Julia P. Owen et al. Abnormal white matter microstructure in children with sensory processing disorders. NeuroImage: Clinical 2 (2013) 844–853

22 AC Wickremasinghe et al. Children born prematurely have atypical Sensory Profiles. Journal of Perinatology (2013) 33, 631–635

23 Boardman JP et al. Impact of preterm birth on brain development and long-term outcome: protocol for a cohort study in Scotland. BMJ Open 2020;10:e035854.

24 Mitchell AW et al. Sensory Processing Disorder in Children Ages Birth–3, Years Born Prematurely: A Systematic Review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 6901220030p1 .

25 J Can et al. Brain Plasticity and Behaviour in the Developing Brain. Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 Nov; 20(4): 265–276.

26 K.J.S. Anand et al . Clinical Importance of Pain and Stress in Preterm Neonates. Biol Neonate 1998;73:1–9

27 Closeness and separation in neonatal intensive care, Acta Pædiatrica ISSN 0803–5253

28 Cortisol levels in former preterm children at school age are predicted by neonatal procedural pain-related stress, Psychoneuroendocrinology (2015) 51, 151—163

29 Infant Medical Trauma in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (IMTN), A Proposed Concept for Science and Practice. Advances in Neonatal Care, Vol. 00, No. 00, pp. 1-9

30 Kangaroo Mother Care: A method for protecting high-risk low-birth-weight and premature infants against developmental delay. Infant Behaviour & Development 26 (2003) 384–397

31 Sandra E. Trehub et al . Singing Delays the Onset of Infant Distress, , Infancy, 21(3), 373–391, 2016

32 Spittle, A., Orton, J., Anderson, P.J., Boyd, R. and Doyle, L.W. (2015). Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. [online] Available at: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005495.pub4/full [Accessed 11 Feb. 2021].

33 Ruth Feldman et al, Maternal-Preterm Skin-to-Skin Contact Enhances Child Physiologic Organization and Cognitive Control Across the First 10 Years of Life. www.sobp.org/journal

34 Montirosso R, et al. Promoting neuroprotective care in neonatal intensive care units and preterm infant development: insights from the neonatal adequate care for quality of life study. Child Dev Perspect. 2017;11(1):9-15. doi:10.1111/cdep.12208

35 Spahn, J.M., Callahan, E.H., Spill, M.K., Wong, Y.P., Benjamin-Neelon, S.E., Birch, L., Black, M.M., Cook, J.T., Faith, M.S., Mennella, J.A. and Casavale, K.O. (2019). Influence of maternal diet on flavor transfer to amniotic fluid and breast milk and children’s responses: a systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 109(Supplement_1), pp.1003S1026S. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/109/Supplement_1/1003S/5456696 [Accessed 12 Oct. 2020].

36 André, V., Henry, S., Lemasson, A., Hausberger, M. and Durier, V. (2017). The human newborn’s umwelt: Unexplored pathways and perspectives. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1), pp.350–369.

37 Mennella, J.A. and Bobowski, N.K. (2015). The sweetness and bitterness of childhood: Insights from basic research on taste preferences. Physiology & Behavior, [online] 152, pp.502–507. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S003193841500298X?via%3Dihub.

38 Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals (2011) Guidelines For the Use of The Cuskiboo, NHS Trust

39 Jones, E. & Spencer, S. (2005) How to achieve successful preterm breastfeeding. Infant. Vol 1(4), pp. 11-15

40 Sparshott, M. (1997). Pain, Distress and the Newborn Baby. Oxford. Blackwell Science

41 Fazli, S.M., Mohamadzadeh, A., Salari, M. and Karbandi, S. (2017). Comparing the Effect of Non-nutritive Sucking and Abdominal Massage on Feeding Tolerance in Preterm Newborns. Evidence Based Care, [online] 7(1), pp.53–59. Available at: http://ebcj.mums.ac.ir/article_8506.html [Accessed 29 May 2020].

42 Gotsch, G. (1995). Pacifiers: Yes or No? New Beginnings. 12 (6). p172-173.

43 Reid, T. and Freer, Y. (2000). Developmentally focused nursing care. IN Boxwell, G. (ed.) (2000).

44 Foster JP, Psaila K, Patterson T. (2017). Non-nutritive sucking for increasing physiologic stability and nutrition in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews update to 2016, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD001071. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001071.pub3.

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 53 p 33.

45 Kaya, V. Aytekin, A. (2017). Effects of pacifier use on transition to full breastfeeding and sucking skills in preterm infants:a randomised controlled trial . Journal of Clinical Nursing. 26 (13-14) p2055.

46 Rainsford, F. (2001). Pacifier Prohibition: Is the evidence relevant to the separated infant? Journal of Neonatal Nursing. 7 (5). p175-179.

47 Stevens B, Yamada J, Lee GY, Ohlsson A. (2013). Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001069. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001069.pub4.

48 Thakkar, P. Arora, K. Goyal, K. Das, R. Javadekar, B. Aiyer, S. Panigtrahi, S. (2016). To evaluate and compare the efficacy of combined sucrose and non-nutritive sucking for analgesia in newborns undergoing

49 Hauck, F.R. (2005). Do Pacifiers Reduce the Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome? A Meta-analysis. PEDIATRICS, 116(5), pp.e716–e723.

50 Shah, V. O’Brien, K. Bracht, M. Warre, R. Ho, H. Chen, C. Davey, C. Ying, E. Campbell, D. Chisamore, B. Lee, S. (2015). Family integrated care” in level II NICUS: Perspectives of administrators, healthcare Personnel, and parents regarding Implementation. Paediatric Child Health. 20 (5).

51 Shaker, C.S. (2013). Cue-Based Feeding in the NICU: Using the Infant’s Communication as a Guide. Neonatal Network, 32(6), pp.404–408.

52 White, A. and Parnell, K. (2013) The transition from tube to full oral feeding (breast or bottle) – A cue-based developmental approach. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. Vol.19 (4), pp.189-197.

53 Thoyre, S., Park, J., Pados, B. and Hubbard, C. (2013). Developing a co-regulated, cue-based feeding practice: The critical role of assessment and reflection. Journal of Neonatal Nursing, 19(4), pp.139–148.

54 Charpak N et al .A randomized controlled trial of kangaroo mother care: results of follow-up at 1 Year of corrected age. Pediatrics 2001 108(5) 1072-1079

55 Luddington-Hoe. Birth-associated fatigue in 34-36 week preterm infants: Rapid recovery with very early skin to skin care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and neonatal Nursing 1999; 28: 94-103

56 Coughlin, M. (2017) Trauma-Informed Care in the NICU. Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for Neonatal Clinicians. New York: Springer.

57 Altimier,L. and Philips, R. (2013) The neonatal integrative developmental care model; Seven neuroprotective core measures for family-centred care. Newborn & Infant Nursing Reviews. Vol.13 (1), pp, 9-22.

58 Hunter J (2010) Therapeutic Positioning: Neuromotor, Physiologic and Sleep Implications. In Kenner, C and McGrath, G. (eds.) Developmental Care of Newborns and Infants 2nd ed. National Association of Neonatal Nurses: Glenview : Illionois.

60 Raineki, C., Lucion, A.B. and Weinberg, J. (2014). Neonatal Handling: An Overview of the Positive and Negative Effects. Developmental psychobiology, [online] 56(8), pp.1613–1625. Available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4833452/ [Accessed 14 Feb. 2021].

61 Fern D., Graves., L’Huilier M. Swaddle bathing in the newborn intensive care unit. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev 2002; 2(1): 3-4.

62 Hall K. (2008). Practicing developmentally supportive care during infant bathing: reducing stress through swaddle bathing. Infant, 4(6), 198–201. Retrieved from https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.napier.ac.uk/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=105584815&site=ehost-live

63 Bliss. (2006). Look at me – I am talking to you. Watching and understanding your premature baby. London: Bliss. Retrieved from: https://shop.bliss.org.uk/shop/files/Lookatme2019WEB.pdf

64 Liaw,J. -J,Yang, L, Chou, H.-L, Yang, M, -H., & Chao, S, -C. (2010). Relationships between Nurse care-giving behaviours and preterm infant responses during bathing: A preliminary study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19 (1-2), 89-99, https://doi.org/10.111/j. 1365-2702.2009.03038.x.

65 Edraki, M., Paran, M., Montaseri, S., Razavi Nejad, M., & Montaseri, Z. (2014). Comparing the effects of swaddled and conventional bathing methods on body temperature and crying duration in premature infants: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of caring sciences, 3(2), 83–91. doi:10.5681/jcs.2014.009

66 Petty, J. (2015). Bedside guide for neonatal care : Learning tools to support practice. London: Palgrave.

67 IASP Task Force on Taxonomy (2003) IASP Pain terminology. Available: https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673 accessed 12/12/2020

68 Anand K.J.S, Stevens B.J and McGrath P.J (2007) Pain in Neonates and Infants (3rdEdition). London: Elsevier

69 Beatriz, V.O., Holsti, L., Linhares, M. (2015) Neonatal Pain and Developmental Outcomes in Children Born Preterm: A Systematic Review. Clinical Journal of Pain. 31(4) pp355-362.

70 Maniam, J., Antoniadis, C., & Morris, M.J. (2014). Early-life stress, HPA axis adaptation, and mechanisms contributing to later life. Frontiers in Endocrinology Vol5(73), pp.1-17.

71 Hynan, M.T., Steinberg, Z., Baker, L., Cicco, R., Geller, P.A., Lassen, S., Milford, C., Mounts, K.O., Patterson, C., Saxton, S., Segre, L., Stuebe, A. (2015). Recommendations for mental health professionals in the NICU. Journal of Perinatology, Vol35 (1), pp.14-18.

72 Allen, K. A. (2012) Promoting and Protecting Infant Sleep. Advances in Neonatal Care, Vol.12 (5), pp.288-291.

73 Craig, J.W., Glick, C., Phillips, R., Hall, S.L., Smith, J. and Browne, J. (2015). Recommendations for involving the family in developmental care of the NICU baby. Journal of Perinatology, [online] 35(S1), pp.S5–S8. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/jp2015142

74 Scottish Government (2017) The Best Start A Five-Year Plan FOR Maternity and Neonatal Care in Scotland. Avaliable:http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2017/01/7728.[Accessed:26 March 2017].

75 BLISS (2016) The BLISS Baby Charter and Family Centred Care. [Online] Avalialable:https://www.bliss.org.uk/about-bliss-baby-charter [Accessed 10 March 2017].

76 Scottish Government (2013) Neonatal Care in Scotland: A Quality Framework [Online] Available:http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2013/03/4910/9.[Accessed:06 March 2017].

77Kenner, C., Mcgrath, J.M. and National Association Of Neonatal Nurses (2010). Developmental care of newborns & infants : a guide for health professionals. Glenview, Il: National Association Of Neonatal Nurses.

78 Patel, N., Ballantyne, A., Bowker, G., Weightman, J. and Weightman, S. (2017). Family Integrated Care: changing the culture in the neonatal unit. Archives of Disease in Childhood, [online] 103(5), pp.415–419. Available at: https://adc.bmj.com/content/103/5/415 [Accessed 26 Nov. 2019].

79 Whitelaw et al. Skin to skin contact for very low birthweight infants and their mothers. Arch.Dis Child 1998; 63: 1377-1380

80 Huang. C. M., Tung, W.S., Kuo. L.L., Ying-Ju, C. (2004) Comparison of pain responses of premature infants to the heelstick between containment and swaddling, J Nurs Res, Vol 12, pp. 31-40.

81 Pölkki, T., Korhonen, A. and Laukkala, H. (2018) Parents’ Use of Non pharmacological Methods to Manage Procedural Pain in Infants. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Neonatal Nursing. [Online] Vol.47 (1), pp.43–51. Available: https://www-sciencedirect-com.knowledge.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0884217517304367 [Accessed 28 Feb 2018].

82 Scottish Government (2017) The Best Start: A Five-Year Plan for maternity and neonatal care.

83 Montirosso, R., Casini, E., Prete, A. D., Zanini, R., Bellu, R. & Borgatti, R. (2016) “Neonatal Developmental Care in Infant Pain Management and Internalizing Behaviours at 18 Months in Prematurely Born Children.” European Journal of Pain, Vol 20 (6) pp. 1010–1021.

84 NICE (2017) Developmental follow-up of children and young people born preterm, available [online] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng72/resources/developmental-followup-of-children-and-young-people-born-preterm-pdf-1837630868677 accessed 31/03/21

85 Altimier, D. & Leslie, B. (2015) Neuroprotective Core Measure 1: The Healing NICU Environment, Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, Vol. 15 (3), pp. 91–96.

86 Dusing, S. C., Tripathi, T., Marcinowski, E. C., Thacker, L. R., Brown, L. F. & Hendricks-Munoz, K. D. (2018) Supporting play exploration and early developmental interventions versus usual care to enhance development outcomes during the transition from the neonatal intensive care unit to home: a pilot randomized controlled trial, BMC Pediatr, Vol 18 (46), pp. 1-12.

87 Craig, J. W. & Smith, R. (2020) Risk-adjusted/neuroprotective care service in the NICU: the element role of the neonatal therapist (OT, PT, SLP), Journal of Perinatology, Vol 20, pp. 549-559.

88 Alan, J. & Jobe, M. D. (2014) A risk of Sensory Deprivation in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, The Journal of Paediatrics, Vol 164 (6), pp. 1265-1267.

89 Altimier, L. and Phillips, R. (2016) The Neonatal Integrative Developmental Care Model: Advanced Clinical Applications of the Seven Core Measures for Neautoprotective Family-centred Developmental Care, Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, Vol 16 (4), pp. 230-244.

90 Hall, S. L., Phillips, R., Lassen, S., Craig, J. W., Goyer, E., Hatfield, R. F. & Cohen, H. (2017) The neonatal intensive parenting unit: an introduction, Journal of Perinatology, Vol 37, pp. 1259-1264.

Last reviewed: 12 November 2021

Next review: 01 November 2024

Author(s): A. Ballantyne – Senior Charge Nurse, NICU Royal Hospital for Children Glasgow. A. Grant – Physiotherapy Service Lead, Royal Hospital for Children Glasgow. N. Matta - Associate Specialist in Neonatology & Neurodisability, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde.

Co-Author(s): Other contributors: G. Bowker – Infant Feeding Advisor, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde; M. Brooks – Neonatal Staff Nurse, Wishaw NICU, Lanarkshire; M. Clark – Infant Feeding Support Nurse/Midwife, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde; G. Currie – Advanced Practitioner Neonatal Occupational Therapist, NHS Lanarkshire; S. Grosse – Paediatric Speech and Language Therapist, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde; A. Hunter – Highly Specialised Physiotherapist, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; K. Lyons – Highly Specialised Physiotherapist, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; S. Russel – Speech and Language Therapist, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; K. Stewart – ANNP, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; N. Patel – Neonatologist, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; C. Wilson – Staff Nurse, Forth Valley NICU.

Approved By: WoS Neonatology Managed Clinical Network

Document Id: 964