Developmental dysplasia of the hips (DDH) and congenital foot deformities

Objectives

This guideline is intended to provide guidance on the investigation and management of infants at high risk of/suspected developmental dysplasia of the hips and other orthopaedic problems. This guidance should be used in conjunction with appropriate local pathways.

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) covers a spectrum of hip abnormalities ranging from hip dysplasia, reducible subluxation/dislocation and irreducible hip joint dislocation.1 The term Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) was coined in 1989, to encompass the dynamic spectrum of hip conditions seen within the first year of life. Approximately 60-80% of the abnormalities identified by physical examination and more than 90% identified by ultrasound resolve spontaneously in early infancy. The late diagnosis of DDH leads to more invasive treatment than if it is diagnosed in infancy, and is associated with a significant rate of premature degenerative joint disease of the hip in early adulthood.

Key definitions2:

- Dislocation: displacement of articulating bones leading to separation of joint surfaces

- Subluxation: incomplete separation of joint surfaces - the femoral head is displaced from its normal position in the acetabulum but remains in contact with it

- Dysplasia: abnormality of development of acetabulum resulting in a shallow and/or dysmorphic socket

The incidence of late diagnosed DDH remains to be 1.28/100 despite a targeted hip screening programme. Reported incidence in the UK is 1.2/1000 live births.

There is a 4-fold increase in females due to increased ligamentous laxity caused by circulating hormone, relaxin. The left hip is involved in 60% of cases (right 20%, bilateral 20%) which may be due to the anterior position of the occiput and limited space for abduction3.

Universal vs targeted hip screening

There is controversy over the use of universal ultrasound in diagnosis of DDH as more than 90% of abnormalities detected resolve on follow-up. A Cochrane review of screening programmes for DDH (2011) concluded there was insufficient evidence to give recommendations. There was inconsistent evidence that universal ultrasound increased treatment rates compared with targeted screening. However, neither strategy was shown to reduce late complications of DDH including late diagnosis or surgery.4 More recently however universal screening has been shown to reduce the risk of late presentation of DDH and the need for surgical intervention (as well as reducing number of surgical procedures required.) Therefore, in Scotland, hip screening is done using targeted risk factors, clinical assessment and targeted hip ultrasound.

Infants with the following risk factors should be referred for a hip ultrasound:

Breech presentation

This exerts mechanical forces on the developing hip joint with frank breech being at highest risk.5 (see high risk infant criteria for more details)

Family history of DDH in first degree relative.

The incidence of DDH increases 12-fold in affected first degree relatives.6 If there is one affected sibling the risk is 60 per 1000 and increases to 120 per 1000 for an affected parent7

Fixed foot deformities

Fixed foot deformities have been shown in studies to be associated with a higher risk of DDH 8,9

Multiple pregnancies, where any of the above risk factors are present. This is because if one baby meets criteria, it can sometimes be difficult to accurately assess which baby was affected.

There is insufficient evidence to support the inclusion of torticollis or oligohydramnios as these have not been proven to increase the risk of “nonsyndromic” DDH.10,11

In general, risk factors are poor predictors of DDH. Female sex, alone, without other known risk factors, accounts for 75% of DDH 12. This emphasizes the importance of a careful physical examination of all infants in detecting DDH.13

The neonatal clinical hip examination is part of the routine new born examination. All hip joints should be examined in a systematic manner using the look, feel, move approach ideally within 24 hours and certainly before 72 hours after birth14. All hips should be re-examined at 6-8 weeks of age for DDH (usually in primary care).

History Before examination, maternal obstetric history, baby’s family history and hip risk factors should be reviewed. Family history of DDH, breech presentation after 36 weeks gestation or fixed foot deformity, are triggers for a hip ultrasound (see risk factors for screening).

Examination Clinical assessment involves an inspection (look), palpation (feel) and (move)ment approach.

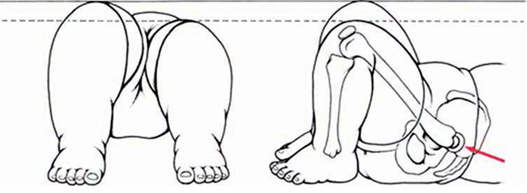

‘Look’: Inspection is important to assess for symmetry of leg length and gluteals.

‘Feel’ – evaluated by flexing the hips and knees. Unequal knee lengths (Galeazzi sign), is a sign of a dislocated hip. A dislocated hip is a more common cause of leg length discrepancy than any other causes.

Leg length discrepancy in a neonate is a trigger for a hip ultrasound.

Figure 215

Figure 215

‘Move’

Gentle abduction test

The hips should be fully flexed and abducted together, to detect any difference between the sides. The examiner's middle fingers are placed on the greater trochanter with the flexed legs contained in the palms. The thumbs rest on the inner side of the thighs opposite the lesser trochanter. Even slight limitation of abduction may be significant, indicating a hip that is starting to subluxate. Asymmetry or reduction of hip abduction of the hip in a neonate is a trigger for a hip ultrasound.

Ortolani and Barlow’s manoeuvres are then performed with the pelvis stabilised by the opposite hand.

Ortolani is a test of hip joint reducibility and Barlow’s for dislocatability. Examine one hip at a time. Ideally the baby should be relaxed and the family reassured that the test is not painful.

Ortolani’s test returns a posteriorly dislocated femoral head back into the acetabulum. It is performed by holding the hip with the thumb over the inner thigh, the middle finger over the greater trochanter and abducting the hip. An abnormal Ortolani test is when the greater trochanter is felt to move forward as the hip reduces into the acetabulum. It must be stressed that reduction of the hip almost never produces an audible sound.

In Barlow’s test, a similar hand position is used and the hips are flexed. Posterior pressure is applied in the line of the femur with the hips in neutral ab/adduction. An abnormal test is when the femur is felt to move backwards relative to the fixed pelvis, and indicates hip instability.

1. H - History

Patients with the following risk factors and a normal clinical hip examination should undergo hip ultrasound within 4-6 weeks corrected gestational age.

- Breech presentation at or after 36 completed weeks of pregnancy, irrespective of presentation at birth or mode of delivery. This includes breech babies who have had a successful external cephalic version (ECV).

- Breech presentation at delivery if ≥ 28 weeks gestation.

- Positive family history in first degree relative

- Foot deformities – calcaneovalgus, fixed talipes equinovarus

- In multiple births, where any of these risk factors are present, all babies in the pregnancy should be referred for a hip USS.10

2. Abnormal Clinical Examination in the neonatal period

I – Inspection – asymmetrical groin creases, leg length discrepancy

P – Palpation – Asymmetrical hip abduction

S – Stability – Either an abnormal Barlow (dislocatable) or Ortolani (dislocated) test – findings will need to be confirmed by an experienced team member. If confirmed, contact the local orthopaedic team-on-call prior to discharge.

NB: Ligamentous clicks without instability (only if outcome unclear)

There is limited evidence in the literature to support hip ultrasound screening in isolated clicky hips without instabiltiy.1,16 However, it can be difficult to differentiate between a clicky hip and an unstable hip, by a non-expert examiner. Therefore, ligamentous clicks should be examined by experienced middle grade staff. If screening outcome is still unclear, then an ultrasound should be performed.

Table 1 14

| Hip ultrasound scan timeframes | |

| Orthopaedic referral and USS within 2 - 4 weeks (organized by orthopaedic team) |

Screen positive

|

| Within 4 - 6 weeks | Screen negative but risk factor positive |

Ultrasound

The ultrasound is a well-established tool for detecting DDH and evaluation of babies with an abnormal examination. The position of the femoral head, acetabular coverage and stability on dynamic testing can be assessed.

The Graf method is used for joint evaluation, with 3 bony landmarks: 1. lower limb 2. plane and 3. labrum. The condro-osseous border should also be on. Both hips are evaluated.

This method classifies joints as:

- Type I – normal

- Type IIa - if alpha angle appropriate for age the Sonographer/Orthopaedics organises a rescan in 3-4 weeks.

- Type IIb - if alpha angle not appropriate for age inform on call paediatric orthopaedic team*

- Type IIc - inform on call paediatric orthopaedic team*

- Type IId – inform on call paediatric orthopaedic team*

- Type III – inform on call paediatric orthopaedic team*

- Type IV – inform on call paediatric orthopaedic team*

*see specific local pathway below

|

Pathways may differ locally: NHS Lanarkshire – All high-risk infants and those with an abnormal clinical examination are referred to the paediatric orthopaedic team using Badgernet. *The on call orthopaedic team do not need to be contacted in NHS Lanarkshire NHS GG&C (Glasgow) – Babies with Abnormal Hip examination are referred to Orthopaedics by telephone by calling the orthopaedic middle grade doctor on duty. This should be followed up by completing the written referral proforma in the appendix below (Appendix 1) and forwarding to the neonatal secretaries to email to the appointments dept. Babies with risk factors but normal examination are referred for hip USS by neonatology NHS GG&C (Clyde) – Babies with Abnormal hip examination are referred to local Orthopaedic services using preform letter (Appendix 2) |

Table 216,17

| Limitations of ultrasound |

| Technical aspects of image interpretation |

| Over diagnosis of DDH and abnormalities that may resolve without intervention |

| After 4-6 months, the femoral head calcifies and anteroposterior (AP) hip xrays are required |

X-rays

X-rays before 4 months have higher false negative rate as in the first few months of life, the bones are predominately cartilaginous which makes x-rays unreliable in assessing the hip structure. When the ossification centre of the femoral head appears after 4-6 months, x-ray may be a useful tool as abnormalities are more apparent.

The aims of early DDH treatment are to achieve stable reduction without complications. The splints used vary. The Pavlik harness is the most commonly used treatment and has a success rate of 95% in dysplastic or subluxed joints. It must be kept on at all times and will be monitored by the orthopaedic team.

Figure 6 Pavlik Harness (with limited hip abduction on the right)18

Figure 6 Pavlik Harness (with limited hip abduction on the right)18

The potential complications of splinting are avascular necrosis of the femoral head and rarely, irreducible

dislocation, femoral nerve or accessory nerve palsies21.

Surgical reduction

Indications: failure of conservative management (splinting) or late diagnosis 6-18 months. In older infants, open reduction is the main stay of treatment.

Parental advice

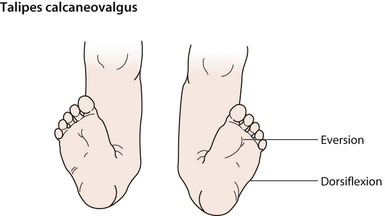

Calcaneovalgus

The mild form is present in 30 to 40% of neonates. The ankle is dorsiflexed so that the foot is positioned against the anterior aspect of the leg. It is usually a positional deformity with easy passive correction.

The vast majority of babies will show spontaneous resolution.

Gentle stretching of the foot into plantarflexion and inversion can be helpful although the majority resolve by 3 to 6 months.19,20

Fixed Talipes Equinovarus (Clubfoot)

Common disorder affecting 1-2/1000 population. Male: female ratio is 2:1. Up to 50% of cases are bilateral. It can be diagnosed antenatally. The foot is turned inward and downward and the forefoot is short, wide, adducted and supinated. The sole of the foot points medially. The involved foot, calf, and leg may be smaller and shorter than the normal side. Should be confirmed by an experienced paediatric team member and referral to local clubfoot service should be made prior to discharge. Gold standard of treatment is the Ponseti method of serial casting and manipulation (successful in >90% of cases).20,21

Positional Talipes Equinovarus

The involved hind foot is in correctable equinovarus (foot is turned inward & downward but easily correctable). Can be easily corrected by pushing the foot up into a normal position. If unsure, infant should undergo senior paediatric review to confirm positional talipes and referral to physiotherapy. An advice leaflet is available from the STEPS charity (see below)

Parental Advice

Clyde Orthopaedic Referral Letter (Word doc) (form updated September 2022)

1. Nie K, Rymaruk S, Paton RW. Clicky hip alone is not a true risk factor for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Bone & Joint Journal. 2017.

2. Ultrasound Examination for Detection and Assessment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). 2013.

3. Catford, J.C., Bennet, G.C., and Wilkinson, J.A. Congenital hip dislocation: an increasing and still uncontrolled disability?. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982; 285: 1527–1530

4. Screening programmes for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborn infants. Cochrane systematic review. 2011

5. Kotlarsky P, Haber R, Bialik V, Eidelman M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: What has changed in the last 20 years? World J Orthop 2015; 6(11);886-901

6. Paton, R.W. Does selective ultrasound imaging of ‘at risk’ hips and clinically unstable hips, in developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)∗ produce an effective screening programme? (PhD thesis) University of Lancaster, 2011)

7. Paton RW, Choudry Q. Neonatal foot deformities and their relationship to developmental dysplasia of the hip: an 11-year prospective, longitudinal observational study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009; 91(5):655-658

8. Chou DTs, Ramachandran M. Prevalence of developmental dysplasia of the hip in children with clubfoot. J Child Orthop. 2013; 7(4):263-267

9. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Detection and Nonoperative Management of Pediatric Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Infants Up to Six Months of Age. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2014

10. Barr LV, Rehm A. Should all twins and multiple births undergo ultrasound examination for developmental dysplasia of the hip? A retrospective study of 990 multiple births. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B (1):132–134

11. Bache CE, Clegg J, Herron M. Risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip: ultrasonographic findings in the neonatal period. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2002;11(3):212–218

12. Roposch A, Liu LQ, Protopapa E. Variations in the use of diagnostic criteria for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(6):1946–1954

13. Public Health England. Newborn and Infant Physical Examination Screening Programme Handbook 2016/17. 2016.

14. Boyd S. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH). MSD Manual.

15. Collins-Sawaragi Y, Jain K. How to use… hip examination and ultrasound in newborns? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017; 0:1-7.

16. Tyagi R, Zgoda MR, Short S. Targeted screening of hip dysplasia in newborns: experience at a district general hospital in Scotland. Orthopedic Reviews. 2016; 8 (6640).

17. Paton RW, Choudry Q. Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH): diagnosis and treatment. Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2016;30(6):453-460

18. Pavlik Wheaton harness, Wheaton brace company

19. Sankar WN, Weiss J, Skaggs DL. Orthopaedic Conditions in the Newborn, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2009, 17 (2);112-122

20. Torchia M, Souder C. Calcaneovalgus foot. OrthoBullets, 2018.

21. NHS website Club foot.

Last reviewed: 16 November 2021

Next review: 01 September 2023

Author(s): Dr Sumaiya Mohamed Cassim – Consultant Neonatologist, University Hospital Wishaw; Dr Sairah Akbar - Paediatric ST8 Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow

Co-Author(s): Other Professionals consulted: Mr Rod Duncan – Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; Dr Ruth Allen – Consultant Paediatric Radiologist, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; Miss Claire Murnaghan – Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow; Mr Alastair Murray – Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, University Hospital Wishaw; Miss Kim Ferguson – Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, University Hospital Wishaw / Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow

Approved By: West of Scotland Neonatology Managed Clinical Network