Enteral feeding of preterm infants

exp date isn't null, but text field is

Objectives

This guideline is applicable to all medical and nursing staff caring for preterm infants in neonatal units in the West of Scotland. It aims to describe safe feeding practices for preterm infants, especially those at increased risk of feed intolerance and necrotising enterocolitis. It is not applicable to babies with congenital abnormalities of the GI tract or babies commencing enteral feeds after GI surgery or following a conservatively managed episode of necrotising enterocolitis. This guidance must always be used in conjunction with careful, individualised, clinical assessment.

Evidence supporting guideline recommendations can be found in Appendix 2.

As survival rates for preterm infants improve more emphasis is being put on improving the quality of outcome by concentrating on optimising nutritional management.

The goals of nutritional support in the preterm include:

- Meeting the recognised nutritional requirements of the preterm infant.

- Achieving an acceptable standard of short term growth.

- Preventing feeding-related morbidities, especially necrotising enterocolitis (NEC).

- Optimising long-term outcomes

Nutritional management in neonatal units across networks often lacks uniformity, both between and within units (2, 36). Although there is uncertainty in some areas of nutritional support in preterm infants, standardisation of practice across networks is associated with a reduced incidence of NEC (3).

Evidence based estimations form the basis of published nutritional requirements for preterm infants, the most recent being Tsang 2005 & ESPGHAN 2019 (5,6). The increased nutrient demands are not evenly spread and cannot be met simply by an increased volume of breast milk provision. Similarly, standard term formulae are not appropriate for growing preterm infants.

|

Nutrient |

Term infant |

Preterm infant Tsang 2005 |

Preterm infant 1-1.8kg |

|

|

ELBW (<1kg) |

VLBW (1-1.5kg) |

|||

|

Energy (Kcal/kg) |

95 -115 |

130-150 |

110-130 |

110 -135 |

|

Protein (g/kg) |

2 |

3.8-4.4 |

3.4-4.2 |

4.0 – 4.5 (<1kg) 3.5 – 4.0 (1-1.8kg) |

|

Sodium (mmol/kg) * |

1.5 |

3.0-5.0 |

3.0-5.0 |

3.0 – 5.0 |

|

Potassium (mmol/kg) |

3.4 |

2.0-3.0 |

2.0-3.0 |

2.0 – 3.5 |

|

Calcium (mmol/Kg) |

3.8 |

2.5-5.5 |

2.5-5.5 |

3.0 – 3.5 |

|

Phosphate (mmol/kg) |

2.1 |

2.0-4.5 |

2.0-4.5 |

1.9 – 2.9 |

*Renal losses in the extreme preterm infant may require significantly more sodium supplementation than is outlined above.

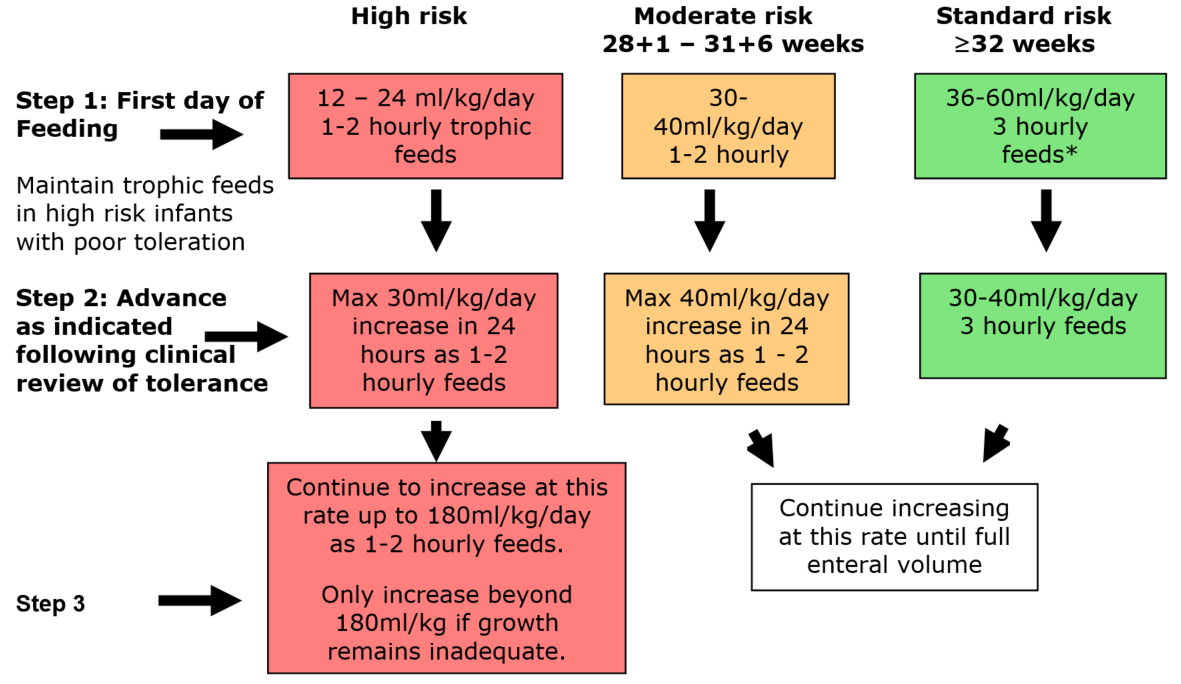

Feeding the preterm infant (see Algorithm 1 & Appendix 5)

When to start feeding

- Evidence supports early enteral feeding.

- Stable infants of any gestation, with no contraindications, should commence enteral feeding as close to birth as possible (7).

- If feeding contraindicated/feeding intolerance, colostrum should be used buccally as mouth care (see below).

- Regular assessment should be undertaken for evidence of any feed intolerance, particularly “high risk”:

|

High risk babies

At clinical discretion the following groups may also be managed as high risk

|

Colostrum as mouth care

Colostrum as mouth care aims to:

- Keep the oral mucosa moist, clean and intact and minimise oral infection

- Keep the lips moist, clean and intact

- Promote comfort, alleviate pain and discomfort

Colostrum as mouth care should be:

- commenced as soon as possible after delivery.

- undertaken at care times / 6-8 hourly.

- freshly expressed colostrum (ideally)

- 0.2-0.3ml drawn up into an oral syringe and used to soak a cotton bud

- Roll bud along lips and gum lines, and over tongue

To continue to promote a positive association between milk and nourishment, ideally continue colostrum as mouth care even when trophic feeds commence until infant is establishing suck feeds.

Trophic feeds

Trophic feeds, defined as initial milk feeds of up to 1ml/kg/hr, aim to prepare the gut for subsequent advancement of enteral feeds.

The benefits of these include stimulating peristalsis, immunomodulatory effects and the growth and maturation of the gut mucosa including the development of tight junctions between the mucosal cells.

These feeds are usually considered “extra” to requirements and are not included in fluid calculations.

- The maximum volume classed as a “trophic feed” is 1ml/kg/hour or 24ml/kg/day. (12)

- Trophic feeds should be considered in very premature or very high risk infants in order to utilise maternal colostrum and stimulate gut trophic hormones. (12)

- The colostrum used for mouth care is separate to the 1ml/kg/hr used for trophic feeding

- There is no recognised consensus on duration or method of delivery. (13)

- Trophic feeds should commence as soon after delivery as possible at 1ml/kg/feed 1-2 hourly. (14)

- Trophic feeds can be initiated and advanced during Ibuprofen treatment. (16)

- Trophic feeding of preterm infants with IUGR and abnormal antenatal Doppler results does not appear to impact significantly on the incidence of NEC or feed intolerance. (17,18)

There is no good evidence that slow advancement of feeding in very low birth weight infants reduces the risk of NEC (17,18,19). Reaching full enteral feeds faster results in earlier removal of vascular catheters, less sepsis and fewer other catheter-related complications. (18) The SIFT trial concluded there is no evidence that slower advancement in feeds reduces risk of NEC, even in those infants thought to be at “high risk” (20).

As such it is recommended that for:

High risk Infants (as defined above)

- Evidence supports early enteral feeding.

- Commence trophic feeds as soon after delivery as possible, for approximately the first 24 hours after introduction and/or until clinical assessment suggests they are well tolerated

- Thereafter, feeds should be increased in increments equivalent to 30ml/kg/day

- Assess the infant’s feed tolerance frequently (with each set of cares) for evidence of intolerance.

Moderate risk infants

28+1 weeks – 31+6 weeks with no ‘high risk’ clinical indicators

- Commence feeds of 24ml/kg/day, divided into 1-2hly feeds, as soon after delivery as possible.

- Thereafter, feed volumes should be advanced in increments of 30-40ml/kg/day

- Assess the infant’s feed tolerance at least twice daily, before making each increment in feed volumes.

Standard risk infants

≥32 weeks with no ‘high risk’ clinical indicators

- Following individual clinical assessment, infants may commence feeds at 60-90ml/kg/day divided into 3hly feeds as soon after delivery as possible.

- Note some babies may increase beyond this volume to maintain normoglycaemia

- Thereafter feed volumes should be advanced daily by increments of 30-40ml/kg/day, as tolerated, until the maximum required feed volume is achieved.

- Assess infant’s feed tolerance daily before making each increment in feed volumes.

NICE recommends: For babies born before 28+0 weeks, consider stopping parenteral nutrition within 24 hours once the enteral feed volume is 140 to 150 ml/kg/day.

For preterm babies born at or after 28+0 weeks, consider stopping parenteral nutrition within 24 hours if the enteral feed volume tolerated is 120 to 140 ml/kg/day.

Locally we have agreed that, to minimise infection risk, removal of lines may be considered once an infant is making good progress with feed advancements and has reached an intake of at least 120ml/kg/day of feeds.

Following discontinuation of TPN, infants then continue to increment feed volumes at the same rate until they reach 165 ml/kg/day of enteral feeds as per Algorithm 1.

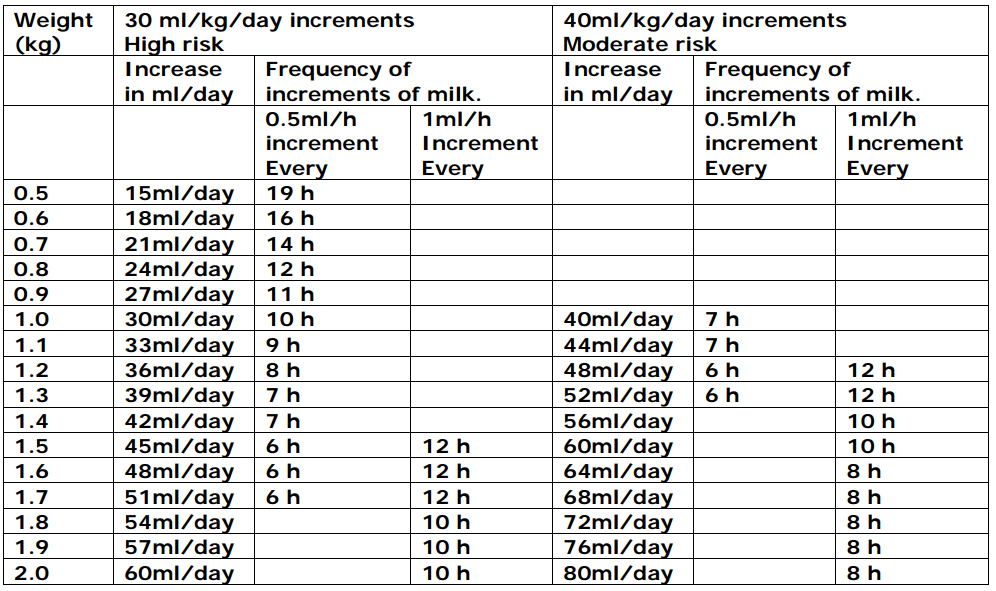

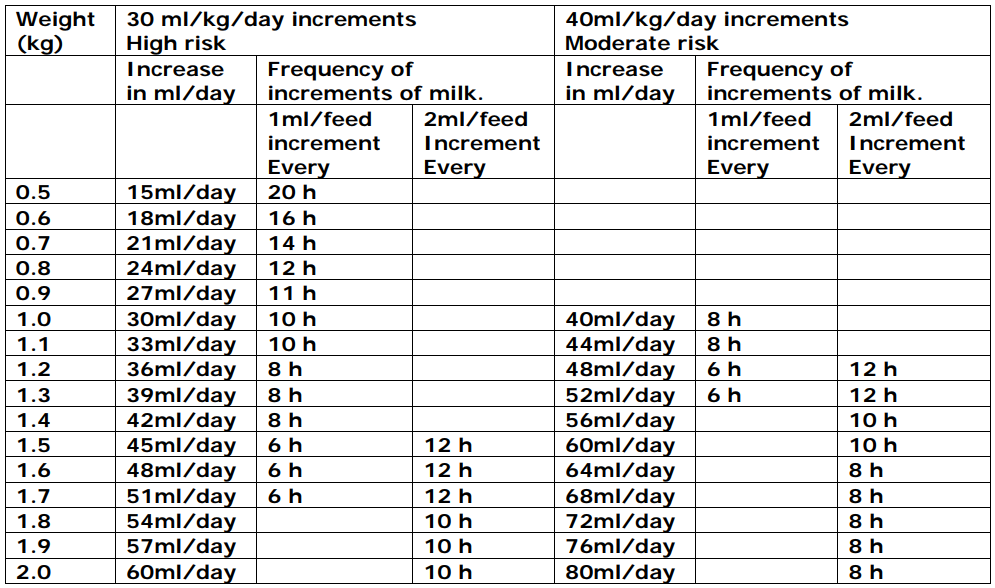

These tables are offered as a guide to the frequency of feed increments

1 Hourly feeding regime

2 hourly feeding regimen

Withholding feeds is a significant decision for infants in the NICU, particularly extremely low birth weight infants and is a contributor to poor growth in the preterm infant. (21) Calories and nutrients can be more safely and more easily delivered by enteral feeds than by intravenous nutrition, without increased cost and increased risks of complications.

However, some infants with feed intolerance may have significant intra-abdominal or other problems.

Undigested Milk Residuals

Gastric residual volume and colour of aspirate may indicate level of gut maturity rather than gut dysfunction and as volumes vary in the early stages of feeding significant increases should not be used in isolation when deciding to limit advancement of feeds.

Routine measurement of gastric residual volume in an otherwise clinically well preterm infant is not recommended.

During establishment of feeds it is common to find small quantities of bile in the gastric residuals.

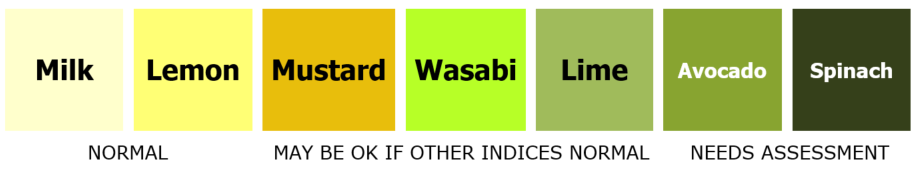

Indicative Colour Chart for Assessing Aspirate Colour (22)

Note that colostrum may appear yellow in colour.

Some infants will have bilious aspirates that are bright yellow in colour in the initial phases

Routine gastric residual volume measurement is not recommended in the preterm infant. Recent studies have shown no increased risk of adverse events when not routinely aspirating. If gastric residual volumes are aspirated due to clinical concerns, these should be “re-fed” providing:

- Residual volumes consist of undigested milk.

- Residual volumes, including bile stained, are present during low volume/ trophic feeding

Signs of intolerance:

- Vomiting (eg 2 or more moderate vomits)

- Abdominal distension

- Heavily bile-stained gastric residuals or vomiting (“lime”, "avocado" or "spinach" in the reference chart below) (Bile stained aspirates – see above)

Possible signs of Necrotising Enterocolitis (NEC):

- Bilious/ fresh blood stained aspirates

- Visual bowel loops/abdominal discolouration

- Grossly bloody/watery or abnormal stools (FOB testing is not helpful)

- Clinically unstable or acute deterioration

Suggested interventions if signs of intolerance, or possible NEC, present:

- Medical review

- Consideration of septic screen and/or abdominal x-ray

- If no clear signs of NEC, consider continuing with trophic feeds rather than stopping feeds completely

Current evidence does not support the firm recommendation of one strategy among the many alternatives, however published data indicate that:

- Bolus feeding may be more physiological in the preterm infant. (26)

- Bolus fed infants may experience less feed intolerance and have a greater rate of weight gain. (27)

- Infants fed continuously take the same length of time to achieve full feeds as those fed bolus feeds. (27)

- Growth may be compromised by continuous feeding as human milk fat adheres to the tubing. (28)

- Bolus feeding enhances protein synthesis more than continuous feeding, and promotes greater protein anabolism (29,30)

- There is no significant difference in somatic growth and incidence of NEC between feeding methods. (32)

- Behavioural stress responses may be higher in bolus fed infants. (31,32)

Gastric administration of feeds is recommended; transpyloric feeding in preterm infants has been associated with a greater incidence of gastrointestinal disturbance. (33) In general we recommend 2 hourly feeds in most infants <32 weeks , but 1 hourly feeds may help with feed intolerance in the ELBW infant. Infants should be progressed to 3 hourly feeds when feed tolerance is no longer problematic.

- Maternal EBM

- EBM fortifier

- Probiotics

- Protein supplements

- Donor EBM

- Preterm formula

- Nutrient enriched post discharge formula

- Specialised term formula

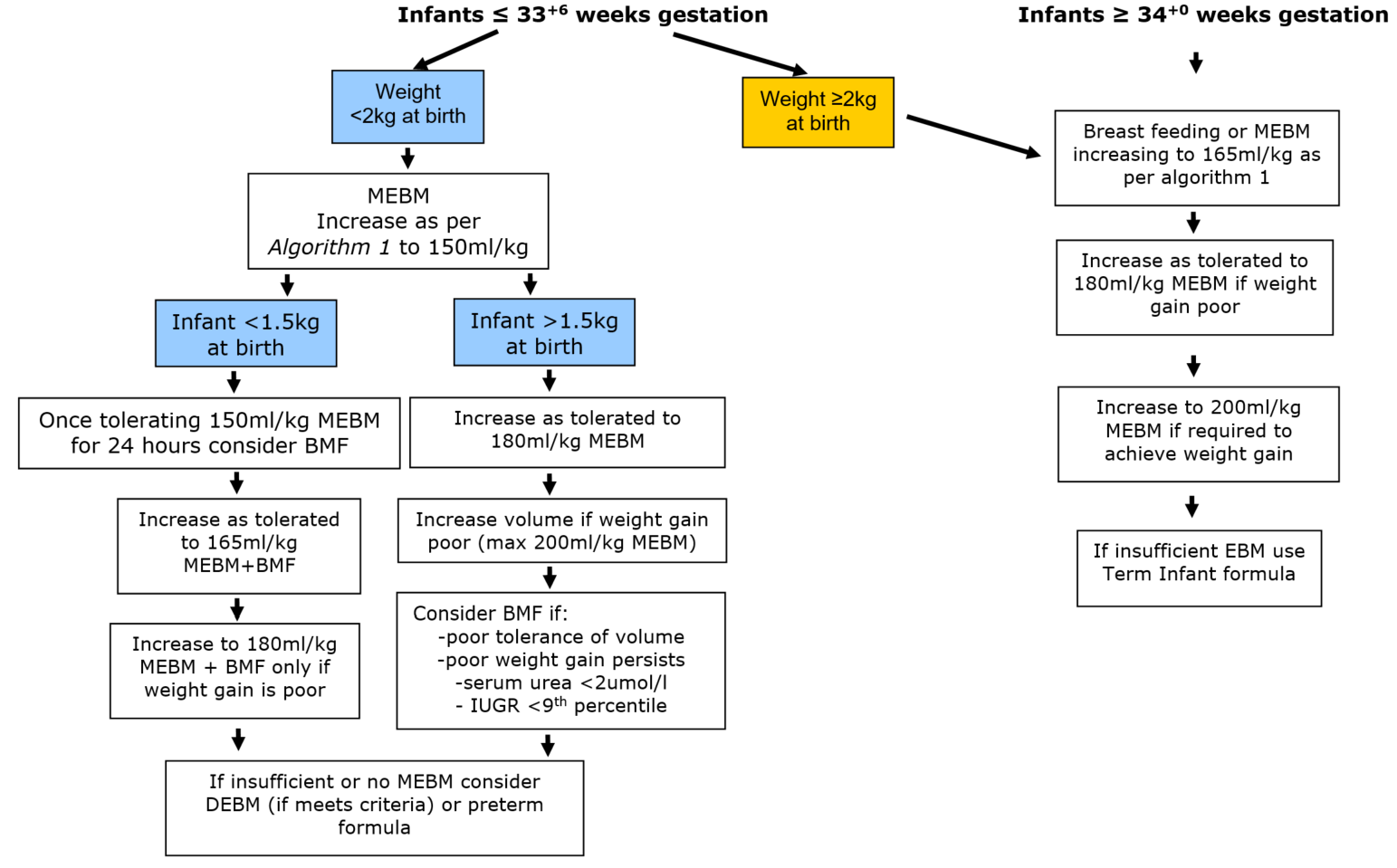

Maternal Expressed Breast milk (MEBM)

Breast milk expressed by the infant's mother is the gold standard of care for preterm infants. Advance to an initial volume of 150ml/kg/day increasing to 180-200ml/kg/day as indicated by weight gain and volume tolerance.

Infants <34 weeks and <1500g

Even at 180 – 200 ml/kg/day, expressed breast milk does not provide sufficient protein, and may not provide enough calories, to support optimal growth of the preterm infant. Early fortification should be considered to avoid these nutritional deficits. In general, Breast Milk Fortifiers (BMF) are added to maternal expressed breast milk (EBM) for infants born <34 weeks and <1500g, once they have been established on 150ml/kg/day of enteral feeds for at least 24 hours.

Infants with a birth weight ≥1500g but <2000g

Consider BMF if:

- Volumes of 180-200ml/kg/day EBM are not likely to be tolerated

- Serum urea falls <2 mmol/l

- Weight gain is <15g/kg/day on maximum volumes tolerated or

- IUGR where birth weight for gestational age is <9th centile.

Breast Milk Fortifier may not be required if 50% or more of the feed requirement is provided by preterm formula, though it can be considered if there is associated poor growth and suboptimal tolerance of volume. In practice this would depend on having adequate volumes of milk to fortify accurately. Where preterm formula is required in addition to EBM, this can be given as either mixed or alternating with feeds of EBM+BMF or only used once supplies of EBM have run out, until the next expression. There is no evidence to support one practice over the other, but the method involves the least amount of milk handling is likely to be the best for individual infants. BMF should never be added as a supplement to preterm formula.

Breast milk should be fortified with one of the commercially available, multicomponent breast milk fortifiers that are designed to meet the needs of preterm infants.

- Nutriprem BMF (Cow & Gate) - containts protein (extensively hydrolysed whey), carbohydrate, vitamins and minerals. Fat-free.

- SMA BMF (Nestle) – contains protein (whole cow’s milk protein), carbohydrate, vitamins and minerals, and a trace of fat.

- Both fortifiers are produced in powder form and are packaged into sachets

For further advice see the guideline for Expressed breast milk

Preterm infants less than 32 weeks’ gestation should receive supplementary phosphorus which should be titrated against normal serum phosphate and ALP levels- see Bone Health guideline.

Evidence regarding the use of probiotics remains mixed. Current research shows evidence of benefit however data remains heterogenous in probiotic used and dosing regimen.(39)

Current evidence suggests probiotics are beneficial in the reduction of necrotising enterocolitis and should be considered in infants <32 weeks and <1500g. (40) It should be noted that there is less evidence in the ELBW (<1000g) infants. (41)

Continued research is ongoing with regards to the use of probiotics in the preterm infant however it is suggested that there is enough evidence of benefit to support introduction of probiotics.

Following a protocol already initiated as routine in a tertiary level neonatal unit, initiation of probiotics would be proposed as follows:

- Speak to parents and offer them written information (this guideline or PIL or both if they would like). Specific written consent is not needed but information should be available for parents so they understand why we choose to use probiotics and then document this in the notes (as we do for blood transfusion.)

- Start probiotics in any baby born <32 weeks or <1500g within 48 hours of commencing enteral feeds

- Prescribe on drug kardex as follows: LaBiNIC 0.16ml once daily via NG or Orally.

- LaBiNIC is drawn directly from the bottle and given without further dilution either orally or via NGT. Always shake the bottle prior to use. As LaBiNIC is an oily suspension milk should then be recommenced to ‘flush’ the dose through the NGT and prevent blockage. If a child is on bolus feeds we suggest giving the dose prior to a feed.

- Continue Probiotics until around 34 weeks corrected age (earlier or later discontinuation at consultant discretion)

- Consider temporary discontinuation in any baby who is seriously unwell or septicaemic and highlight its use in any discussions with the Microbiology consultan

Protein supplementation of human milk in relatively well preterm infants results in increases in short term weight gain, linear and head growth.

Protein supplementation should be considered in VLBW infants who are predominantly fed maternal/donor breast milk. NB. Protein supplements should not be added to formula milk

Protein supplements should be considered in infants <35 weeks if:

- Protein needs not met by fortified EBM

- Urea <4mmol and falling

- Infant is at least 14 days old, on a minimum of 150ml/kg/day (>50% EBM)

Contraindicated in babies >37 weeks, on gaviscon, or on >50% formula milk

Caution post GI surgery or if continuous feeds

Dosage (42):

- 1 sachet per 50ml if on EBM alone

- 1 sachet per 100ml if on fortified EBM

If on fortified EBM with protein supplements total fluid volume should not exceed 150ml/kg/day due to a theoretical risk of protein toxicity.

See Appendix 4 for a suggested method for prescribing and making up protein supplements.

In the absence of a mother's own expressed breast milk, donor breast milk, where available, will generally be the milk of choice (43,44). Parental consent is required prior to use.

- <30 weeks gestation

- Birth weight <1500 grams

- <32 weeks gestation and intra uterine growth restriction (weight <9th percentile) and abnormal antenatal Doppler’s (absent / reversed end diastolic flow)

- Previous proven NEC

- Congenital heart disease with potential for gut hypoperfusion

- DEBM is recommended for all infants <1500g and would be strongly advocated in those infants <1000g and/or <30 weeks gestation.

- If DEBM is used where MEBM is not established, it is recommended to continue until the infant is 34 weeks corrected gestation, when risk of NEC has substantially reduced.

- Once full milk feeds have been established and a substantial proportion remains DEBM, milk should be fortified with breast milk fortifier as per local guidelines.

If transitioning to formula milk, this should be done as follows: initially ¼ formula: ¾ DEBM for 24-48 hours, then ½ formula: ½ DEBM for 24-48 hours, ¾ formula: ¼ DEBM for 24-48 hours and finally all formula.

Where maternal EBM is not available preterm formulas are to be used for babies born <34/40 and <2000g who have none of the risk factors outlined above. Advance to an initial volume of 150ml/kg/day increasing to 165-180ml/kg/day as indicated by weight gain and volume tolerance.

Volumes >180ml/kg/day should not be necessary and other reasons for poor growth sought before further volume increases are introduced.(Appendix 1)

- Feed to initial volume of 165ml/kg increasing as indicated by weight gain and volume tolerance.

- Infants born >1000g will have their protein requirements met by 165ml/kg

- Infants born <1000g will have their protein requirements met by 180ml/kg

- Volumes >180ml/kg are not usually necessary and other reasons for poor growth should be sought before further volume increases are introduced.(Appendix 1)

Nutrient Enriched Post Discharge Formulas (NEPDF)

A Cochrane database review has not found any consistent improvement in infants routinely given one of these formulae. They are only indicated where poor growth persists at discharge or where there are concerns about ongoing deficiencies of Na+ or PO4

(At consultant discretion) This must be arranged with the GP and health visitor, and should be commenced a few days before discharge. There are two NEPDFs available in the UK, Nutriprem 2 and SMA Gold Prem 2. Both formulae are available on prescription for preterm infants from 35 weeks CGA until 6 months post term corrected age.

Term formula is the complementary feed of choice for infants born 34-37 weeks. Similarly, growth restricted term infants >37 weeks, should be offered term formula in the absence of maternal milk. (38)

Specialised term formulas (Appendix 4)

None of the specialised term formulas are designed for use in the preterm infant. Energy needs may be met by increased volumes but these are often poorly tolerated. Concentration of formulas should never be undertaken unless under direct dietetic supervision.

Specialised formulas ideally require making up from powder within a Feed Unit/Milk Kitchen environment. They will be non sterile and have potentially inconsistent composition. All powdered feeds should be made up in accordance with the Department of Health guidelines for the Use of Powdered feeds in a Hospital Environment. (45,46)

Specialised formulas should only be used where absolutely necessary and ideally under the direction of a Paediatric and Neonatal Dietician.

Soya formulas are not recommended for infants unless specifically required for treatment of galactosaemia or as part of a vegan diet. (47)

Vitamin supplementation for babies on parenteral nutrition

SMOFvits® contains 20ml of Vitlipid N® (4600 IU vitamin A and 800 IU vitamin D) per 100ml.

For every 1 gram/kg/day of SMOFvits® the infant will receive 270 IU vitamin A and 47 IU vitamin D. These amounts are well within recommended, especially for the smallest infants, even with the addition of Dalivit®.

Oral Vitamin supplementation for preterm infants (<34 weeks gestation)

Eligible infants – all infants < 34 weeks gestation

Commencement of treatment – once baby tolerating ≥ 100ml/kg/day enteral feeds.

Supplements should commence even if the baby is still receiving some SMOFvits®

Dose:

DaliVit® 0.6ml (or 16 drops), orally, once daily

0.6ml DaliVit® contains:

5000 IU vitamin A

400 IU vitamin D2

50 mg vitamin C

Thiamine, riboflavin, pyridoxine and nicotinamide

These routine supplements should be continued at least until the baby is on a good mixed weaning diet – usually over 1 year chronological age.

Iron – Sytron® (sodium feredetate):

Eligible infants – born at < 34 weeks’ gestation

Commencement of treatment – 28 days of age (or at discharge if sooner)

Dose:

0.5ml twice daily, orally, (equivalent to 5.5mg elemental iron/day)

N.B. May be given in a single daily dose of 1ml if preferred

These routine supplements should be continued at least until the baby is on a good mixed weaning diet including foods rich in iron, such as meat and green vegetables – this is usually until around 1 year chronological age.

Notes:

Higher doses are required to treat established iron deficiency – see formulary

Iron preparations may cause constipation (generally after discharge); in this case, it would be reasonable to reduce the dose by half.

This algorithm is to be used in conjunction with Algorithm 2 – choice of milk

Commence feeding as close to birth as possible following individual clinical assessment. Maintain trophic feeds in high risk infants as long as clinically indicated.

Infants can move between risk categories following individual clinical assessment.

Particular attention should be paid to assessing feed tolerance in the following infants:

- <28 weeks gestation

- < 1000g birth weight

- Preterm SGA infant (<2nd percentile and <34 weeks gestation)

- Absent or reversed end diastolic flow in infants <34 weeks

- Unstable /hypotensive ventilated neonates

- Perinatal hypoxia-ischaemia with significant organ dysfunction.

- Congenital gut malformations (eg gastroschisis)

- Severe SGA infants (<0.4th percentile and ≥34 weeks gestation)

- Ibuprofen for PDA

- Complex congenital cardiac disease

- Dexamethasone treatment

* At clinicians discretion - Standard risk infants who are well may commence on sufficient milk feeds to maintain normoglycaemia, thus avoiding the need for IV fluids. Otherwise follow the algorithm above.

Fresh maternal breast milk is the first milk of choice for all infants unless clearly contraindicated

>180ml/kg should rarely be required in infants receiving preterm formula or fortified EBM.

Alternative reasons for poor growth should be examined before volumes >180ml/kg are implemented. (appendix 1)

Small for gestational age

Low birth weight infants (<2.5kg) born at term have nutritional requirements that differ from those of appropriate weight infants born at term. These requirements are different again to those of infants who are preterm and appropriate for gestational age as well as those who are preterm and small for gestational age.

Actual requirements are unknown. A baby who is small at term is likely to have better stores of some nutrients than the infant born prematurely. Comparatively the infant who is both preterm and small for gestation is likely to have the poorest stores of all nutrients.

Expected weight gain

The weekly completion of an appropriate growth chart is the best indicator of growth for an infant, however parents frequently ask how much weight their infant is expected to make on a daily basis. The most frequently used range is 15 – 20g/kg/day, but a good guide for an infant born during what would have been their third trimester would be 18g/kg/day up to 2kg then 30g/kg/day thereafter.

Growth monitoring

All infants should be accurately weighed at birth with note taken of any oedema present. Head circumference should be measured on the day of birth and both parameters plotted on a 2009 UK-WHO Close Monitoring Charts via paper charts or electronic method (Badgernet or iGrow).

Weight should be measured two to three times per week in SCBU for the purpose of growth monitoring but on a daily basis in the NICU where the management of fluid balance is critical. All weights are to be recorded on nursing charts and plotted weekly on the growth chart.

Length measurement is an additional growth monitoring tool, though a difficult measurement to obtain accurately. Frequency of measurement, method and equipment used is at physician discretion.

Growth failure

Infants born preterm accumulate significant nutrient deficits by the time of discharge from hospital (49, 50). These can manifest as growth deficits that persist through infancy and early childhood (51) into adolescence. (52)

Factors contributing to nutrient deficits are numerous, though fluid restriction is often the greatest contributor. The majority of infants will meet their nutritional requirements with between 150 and 180ml/kg of an appropriate feed, therefore interruption and reductions in feeds to below 150ml/kg should be minimised. Where prolonged fluid restrictions are unavoidable in the older formula fed infant eg cardiac disease, consideration should be given to the use of nutrient dense term formulas such as SMA High Energy or Infatrini.

Conversely volume increases above 180ml/kg should only be implemented once consideration has been given to the range of other factors known to impact on growth:

- Use of the most appropriate feed for the infant.

- Adequacy of human milk fortification.

- Sodium depletion-identified by low plasma levels.

- Anaemia.

- Sepsis/trauma in the short term.

- Steroid treatment, which can delay length growth for 3-4 weeks after cessation of therapy.

- High energy requirements secondary to cardiac/respiratory condition.

- Low serum urea as an indicator of protein status.

- Organic causes of growth failure.

When to start feeding.

The objective of early feeding is to stimulate gut maturation, motility and hormone release. As starvation leads to atrophy of the gut, withholding feeds may render subsequent feeding less safe and protract the time to reach full enteral feeding. (2) A systematic review of 10 trials of early introduction of feeding conducted in 2005 (9) concluded that early introduction of feeding did not increase the incidence of NEC and shortened the time to both full feeds and discharge. This review was updated in 2013 (11) and the conclusions remained the same. These findings were confirmed by a further controlled trial along with a significant reduction in serious infections with “early” enteral feeding. (43) Preliminary reports from the ADEPT trial indicate that growth restricted preterm infants born after absent or reversed end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery who are fed from the second day after birth achieve full feeds earlier than those commencing feeds on day 6 with no increase in the incidence of sepsis or NEC(8). No work has yet addressed whether initial feeds should be exclusively breast milk (mother's own or donor); most evidence suggests that any enteral feed given early may be better than gut starvation.(12)

Colostrum as mouth care

Studies have been conducted comparing colostrum with sterile water as mouth care and outcomes conclude that oropharyngeal administration of colostrum may decrease clinical sepsis, inhibit secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increase levels of circulating immune-protective factors in extremely premature infants. (10)

In addition, in sick and/or preterm infants, it has been shown to:

- Provide a positive oral experience

- Support early sensory development of taste and smell

- Promote absorption of maternal antibodies and anti-inflammatory substances through the oral mucosa can protect against disease and infection (9)

- Provide bactericidal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory protection (10)

They also comment that when infants are able to absorb colostrum through the oral mucosa they also absorb maternal antibodies and anti-inflammatory substances which are protective against disease and infection. (9)

A study by Lee et al (2015) reported reduced rates of ventilator acquired pneumonia, infection and necrotising enterocolitis in infants who were given colostrum as mouth care versus sterile water. (10)

No studies have been conducted comparing the protective benefits of colostrum as mouth care versus trophic feeding. Larger studies are warranted in particular looking at the oropharyngeal exposure to colostrum as a potential protective measure against sepsis and NEC.

Trophic feeding

Trophic feeds are small volumes of milk given to stimulate the bowel that are maintained for up to 7 days and not intended to contribute to nutrition. The maximum volume is 1ml/kg/hour or 24ml/kg/day.(9) There is no recognised consensus on duration or method of delivery.(10)

Evidence suggests that trophic feeding is beneficial for reducing length of stay and infection rates without increasing the risk of NEC (10), although the most recent Cochrane review (9) concludes that available trial data do not provide evidence of important beneficial or harmful effects of early trophic feeding for very preterm or very low birth weight infants. They commented that the applicability of these findings to extremely preterm, extremely low birth weight or growth restricted infants is limited. In a small recent study early trophic feeding of preterm infants with IUGR and abnormal antenatal Doppler results did not have a significant impact on incidence of NEC or feed intolerance.(12) None of the papers makes recommendations for optimal duration of trophic feeds and all call for further research.

Rate of increase of feeds

The recent Cochrane review on rate of advancement of feeds concluded that available trial data suggested that advancing enteral feed volumes at daily increments of 30 to 40 mL/kg (compared to 15 to 24 mL/kg) does not increase the risk of NEC or death in VLBW infants. Advancing the volume of enteral feeds at slow rates results in several days of delay in establishing full enteral feeds and increases the risk of invasive infection. They did however comment that the applicability of these findings to extremely preterm, extremely low birth weight, or growth-restricted infants was limited and that further randomised controlled trials in these populations may be warranted to resolve this uncertainty. (13)

The most recent evidence from the SIFT study showed that slow advancement of feeding in very low birthweight infants did not reduce the risk of NEC showing no advantage in increasing at 18ml/kg/day versus 30ml/kg/day. (14)

Assessing feed tolerance

The volume of feed aspirated from the stomach prior to a feed is one of the factors used to judge progression of feeding. It is important to note that volume and colour of aspirate may indicate level of gut maturity rather than gut dysfunction (17).

Gastric motility more rapidly normalises if feeds are started early and offered frequently rather than being withheld.(50) Despite this feeds are frequently stopped, or advances held on the basis of “feed intolerance”. The definition of intolerance includes not only the presence and colour of gastric residuals, but also vomiting, increases in abdominal girth or abdominal tenderness, presence of abnormal or blood stained stool, absence of bowel sounds, abdominal wall discolouration, or a combination(1). As all of these can occur in the healthy premature infant who is tolerating feeds(55) careful clinical assessment is essential to prevent unnecessary limitations of enteral feeds, reliance on parenteral nutrition, increase nosocomial infection, delay enteral feeding and poor growth.

Clearly defining feeding intolerance can lead to dramatic improvements in nutritional outcomes. (57)

Gastric residuals up to 2ml in infants <750g and up to 3ml in infants 750g – 1500g were treated as normal in the studies by Mihatsch and Bertino(54,16).

Maximum gastric residuals in premature infants who develop NEC have been shown to be 40% of feed volume compared to 14% in those who did not develop NEC, with residuals increasing dramatically over the three days before the onset of NEC.(17) For the early detection of VLBW infants at risk for NEC, both gastric residual volumes and bloody residuals represent an early relevant marker.(16) Where feed intolerance does occur continuing with trophic feeds rather than stopping feeds has been associated with less sepsis and shorter time to full enteral feeds with no increase in NEC.(55)

A recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics (97) showed that preterm infants (<32 weeks <1250g) who did not have their gastric residual volume measured routinely reached full enteral feeds quicker, had fewer episodes of abdominal distension and no increase in NEC.

As residuals vary so much in the early stages of feeding significant increases should not be used in isolation when deciding to limit advancement of feeds(1).

Frequency and method of delivery

Feeds given by intermittent bolus method promote a cyclical surge of gut hormones similar to that in adults and term infants so are considered more physiologic in the preterm infant (17). They also experience less feed intolerance and have a greater rate of weight gain when fed a bolus technique compared to continuous infusion (18). Animal studies have shown enhanced protein synthesis in bolus versus continuous feeding. (19) A recent Cochrane review showed no differences in time to achieve full enteral feeds and no significant difference in growth, days to discharge or the incidence of NEC and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support one method over the other. (20). Previous authors have demonstrated that continuously fed infants achieved full feeds more quickly than those receiving bolus feeds, however no assessment was made of growth and feed tolerance in the longer term – there are risks that growth could be compromised as human milk fat adheres to the tubing during continuous feeding (19). Higher behavioural stress responses in bolus fed infants have recently been reported by the same group (21), and a 2014 study reported splanchnic oxygenation changed significantly over time and differed between the two feeding techniques, with a significant increase after bolus feeding and a reduction during continuous feeding.(22) These findings need balancing against the advantages reported for bolus feeding .

Occasionally intolerance is seen in a bolus fed preterm infant with duodenal motility decreasing following a feed (56), however a bolus feed administered over a longer period of time results in a return of motility and improved tolerance.(57)

Gastric feeding stimulates digestive processes whereas transpyloric feeding has the potential benefits of delivering nutrients past the pylorus and gastro oesophageal junction for the management of gastro oesophageal reflux (GOR) disease. These feeds have to be continuous, which may account for the reduction in symptoms of GOR. Transpyloric feeding is not routinely recommended in preterm infants as no benefits have been found and they have been associated with a greater incidence of gastrointestinal disturbance. (22)

Maternal breast milk

Human milk is the preferred feed for premature infants as it offers in the short term, strong protection against infection and necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), and in the long term improved neurocognitive development. Recent evidence shows the reduction in NEC risk using human milk to be dose dependent. (59)

Maternal breast milk (handling)

See WoS Guideline Expressed Breast Milk: Guideline for expression, storage and use

Donor breast milk (DBM)

In the absence of a mother's own expressed breast milk donor milk is generally considered the next milk of choice. Observational studies suggest that donor milk is similar to mothers own milk with regard to improved feed tolerance (62) anti infective properties and reduced NEC risk (63, 55). Both the role of donor milk in current neonatal practice and the feasibility, cost and impact of its use on nutrient intake, growth and development remain to be established (32, 33).

Current UK practice strongly advocates the use of donor milk as a supplement to mother's milk or to establish enteral feeds. Likewise the recent AAP publication on use of DBM recommends use for those infants <30 weeks gestation and/or <1500g.

Donor milk generally has a lower calorie content than milk expressed by the mother of a preterm infant, reflecting the fact that much of the donated milk comes from lactating mothers of older term infants.

It is important to bear in mind that donor milk is a human body fluid and as such carries risks of transmission of infective agents. All donor screening, handling, testing and processing of DBM in the Milk Bank is carried out according to NICE Guidelines (64). Documentation and traceability of DBM is essential, particularly when milk is transported from a central milk bank to a recipient neonatal unit.

Breast milk Fortification

Increased preterm nutritional requirements persist beyond the time when early milk composition changes to that of mature milk. This often coincides with a slowing of weight gain and a sequential reduction in serum urea, where a level <1.6mmol/l is indicative of a protein intake of <3g/kg (65).

In order to maintain the benefits of breast milk whilst optimising the nutritional status and growth of preterm infants single multi nutrient fortifiers (BMF) have been developed. The two available in the UK are Nutriprem BMF (Cow & Gate) and SMA BMF (Wyeth). Both are bovine based products. Neither formulation has clear indications for introduction nor guidance for infant suitability, so practice varies considerably between units. (36)

Fortification of EBM using dried human milk fortifiers has been studied (66, 67) and showed improved growth but low serum phosphate levels due to inadequate bone mineral concentrations.

Concerns with the use of BMFs include tolerance and effects of storage. Most studies have found no significant problems with the tolerance of fortified EBM (68,69) whilst those investigating gastric emptying have been contradictory (70,71). Storage concerns include the reduction of anti infective components (72), increased bacterial loads (73) and increasing osmolality over time secondary to hydrolysis of glucose polymers by human milk amylase (74). The majority of these effects can be reduced by adding the BMF as close to feeding as possible, though recent work shows osmolality of fortified EBM reaches a peak within 10 minutes of addition and remains consistent to 24 hours of storage (75). A Cochrane review concludes that although available trial data show that multi-nutrient fortification increases growth rates of preterm infants during their initial hospital admission, they do not provide consistent evidence on effects on longer-term growth or development. Additional trials are needed to resolve this issue it recommends further research seeking to evaluate long term outcomes of BMF therapy and identify the optimum composition of BMF products. (82)

Breast milk is fortified without knowing the nutritional composition of an individual mother's EBM. As the composition of breast milk, particularly protein concentration, varies from one mother to the next and from expression to expression in the same mother, individual analysis prior to fortification would appear to be of value. Such analysis is at present impractical in day to day practice.

Multi-nutrient fortification may be especially important for infants who receive donated (donor) expressed breast milk, which contains lower levels of protein, energy and minerals than their own mother's expressed breast milk. (83)

Protein supplementation

Assumed protein intake in preterm infants fed fortified own mother's milk or banked milk is greater than what infants actually received (85)

- Estimate of milk protein content less than measured protein content

- Protein intakes 0.6 to 0.8 g/kg/day less than estimated

A Cochrane review in 2000 concluded that protein supplementation of human milk in relatively well preterm infants results in increases in short term weight gain, linear and head growth. (86) They found that urea levels are increased, which may reflect adequate rather than excessive dietary protein intake and commented that further research should be directed towards the evaluation of specific levels of protein intake in preterm infants and the clinical effects of supplementation with protein, including long term growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes. This may best be done in the context of refinement of available multicomponent fortifier preparations.

Concerns about protein toxicity have largely been disputed in current research. Hay et al questioned whether an additional 1 g/kg/day would be too much for those infants whose mothers had good milk protein content but concluded that this was unlikely given measurements of human milk protein content, including those in their study, consistently showed that concentrations above 2g per 100 ml are relatively rare. (85) Further, adding 1 g/kg/day of protein to such milk would produce 3g per 100 ml and an intake of 4.5 g/kg/day at 150 ml kg/day, higher than most such infants ordinarily receive, but still within the range calculated to produce normal rates of fetal growth. They also commented the higher milk protein concentrations from mothers providing milk to preterm infants decreases significantly over the first 1 to 3 weeks, research that has been widely duplicated in other studies, making it even less likely that excessive amounts of protein would be provided. Nevertheless, the authors recommend further clinical trials to address potential toxicity.

Probiotics

Probiotic therapy has demonstrated promising efficacy for the prevention of NEC, as evidenced by a very strong treatment effect in favor of probiotic therapy in two recent meta-analyses (40). In an updated systematic review, enteral probiotic supplementation significantly reduced the incidence of severe necrotizing enterocolitis and mortality, with no significant reduction in nosocomial sepsis (41).

Recent data in addition to a report by the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology (ESPGAN) concluded probiotics could be generally considered safe. However, clarity regarding type and dosage strategy continue to temper widespread use and these concerns are likely to remain until large, multicenter trials adequately designed to address safety are completed. (40)

Preterm Formulas

Preterm formulas are designed to meet the basic nutritional requirements of most preterm infants when fed between 150 and 180ml/kg.

There are currently three formulas available in the UK. Nutriprem 1, Aptamil Preterm and SMA Gold Prem Pro.

Preterm formulas can be used as soon as commencement of enteral feeding is recommended. Term formulas should not be used as they fail to meet the nutritional needs of premature infants.

A number of medical conditions may respond to the replacement of standard cows-milk protein infant milk formula with specialist formula. It is important to remember that for the great majority of babies, even those with medical conditions, can continue to breast feed.

This guidance aims to ensure that babies are prescribed appropriate first-line specialist milk.

The paediatric dieticians are always very happy to give advice about individual children and to follow up children in the community. A referral to the paediatric dieticians should always be made for complex conditions and if infants are likely to be on specialist formula long term.

For further information on specialist milks outwith the scope of this guideline please refer to attached resource from First Steps Nutrition trust.

First Steps Nutrition Trust: Specialised infant milks in the UK: infants 0-6 months of age

If baby is on fortified EBM:

Add Cow and Gate Protein supplement powder (1gram) to 3ml EBM (fortified) = 4ml Protein supplement concentrate

Take 2ml of this concentrate and add to 48ml EBM (fortified) to make 50ml.

If the baby is on non-fortified EBM:

Add Cow and Gate Protein supplement powder (1gram) to 3ml EBM (unfortified) = 4ml Protein supplement concentrate

Take 4ml of this concentrate and add to 46ml EBM (unfortified) to make 50ml.

- Nutritional Support of the Very Low Birth Weight Infant. (2008) California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative

- Ziegler E.E. et al (2002) Aggressive nutrition of the very low birth weight infant. Clin Periatol, 29,225-44

- Patole S.K., de Klerk N. Impact of standardised feeding regimens on incidence of neonatal necrotising enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. (2005) Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed; 90: F147-F151)

- Horbar J.D. et al (2003) NIC/Q 2000: establishing habits for improvement in neonatal intensive care units. Pediatrics, 111, e397-410

- Tsang R., Uauy R., Koletzko B., Zlotkin S. Nutrition of the Preterm Infant: Scientific Basis and Practical Guidelines (2005) 2nd Ed: Digital Educational Publishing Inc,.

- ESPGHAN. (2010)Enteral Nutrient Supply for Preterm Infants: Commentary from European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. JPGN;50:1-9.

- Embleton N.D. (2008) When should enteral feeds be started in preterm infants? Paediatrics and Child Health 18[4], 200-201.

- Leaf A., Dorling, J., et al (2010) Early or Late Enteral Feeding For Preterm Growth Restricted Infants? The Abnormal Doppler Enteral Prescription Trial. Arch Dis Child 95(suppl l):A3

- Smith.H (2012) Guideline for Mouth Care for preterm and sick infants. The Northern neonatal Network, www.nornet.org.uk

- Lee.J et al (2015) Oropharyngeal colostrum administration in extremely premature infants: An RCT. Paediatrics;135

- Gephart SM1, Weller M. (2014) Colostrum as oral immune therapy to promote neonatal health. Adv Neonatal Care;14(1):44-51

- Morgan J., Young L., McGuire W. (2013) Delayed introduction of progressive enteral feeds to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD001970

- Morgan J., Bombell S., McGuire W. (2013) Early trophic feeding versus enteral fasting for very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD000504

- Tyson J. E., Kennedy K. A. (2005) Trophic Feedings for parenterally fed infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.Jul20;(3)

- King. C. (2009) What's new in enterally feeding the preterm? Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. Doi:10.1136/adc.2008.148197

- Bellander. M. et al(2003) Tolerance to early human milk feeding is not compromised by Indomethacin in preterms with PDA. ActaPaediatrica: 921074-8

- Karagianni P. et al (2010) Early versus delayed minimal enteral feeding and risk for necrotising enterocolitis in preterm growth restricted infants with abnormal antenatal Doppler results. Am J Perinatol; 27(5):367-73

- Sisk P.M et al (2007) Early human milk feeding is assocoated with a lower risk of necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Journal of Perinatology; 27(7):438-33

- Morgan J., Young L.,McGuire W. (2015) Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

- SIFT

- Cormack BE, Bloomfield FH. An audit of feeding practices in babies <1200g or 30 weeks gestation during the first month of life. Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand 9th Annual Congress, Adelaide, 2005. A42.

- http://www.adhb.govt.nz/newborn/guidelines/nutrition/WithholdingFeeds

- Caple J. et al (2004) Randomised controlled trial of slow versus rapid feeding volume advancement in preterm infants. Pediatrics, 114 1597-600

- Cobb B.A. Et al (2004) Gastric residuals and their relationship to necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics, Jan;113(1Pt 1):50-3

- Bertino E. et al (2009) Necrotising enterocolitis: risk factor analysis and role of gastric residuals in very low birth weight infants. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 48(4):437-442

- Dsilna A, et al (2005) Continuous feeding promotes gastrointestinal tolerance and growth in very low birth weight infants. Journal of Pediatrics; 147(1):43-9

- Premji SS, Chessell L (2011). Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus intermittent bolus milk feeding for premature infants less than 1500 grams. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 11.

- Aynsley-Green A. et al (1982) Feeding and the development of enteroinsular hormone secretion in the preterm infant: effects of continuous gastric infusions of human milk compared with intermittent boluses. Acta Paediatr Scand, 71,379-83

- Davis T., Fiorotto M., Suryawan A. (2015) Bolus versus Continuous Feeding to Optimize Anabolism in Neonates. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care Jan;18(1):102-108.

- Arslanoglu S, Moro GE, Ziegler EE. (2009) Preterm infants fed fortified human milk receive less protein than they need. J Perinatol. 29(7):489-92.

- Dsilna A, et al (2008) Behavioural stress is affected by the mode of tube feeding in very low birth weight infants. Clinical Journal of Pain;24(5): 447-55

- Corvaglia L., Martini S., Battistini B., Rucci P., Aceti A., Faldella G. (2014) Bolus vs. continuous feeding: effects on splanchnic and cerebral tissue oxygenation in healthy preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2014 Jul;76(1):81-5

- McGuire W, McEwan P.(2007)Transpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD003487

- Schanler R.J. Et al (1999) Feeding stratagies for premature infants: beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula. Pediatrics,103, 1150-7

- Daly SEG, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. The short-term synthesis and infant regulated removal of milk in lactating women. Exp Physiol 1993; 78: 379-398.

- Meinzen-Derr J.et al (2009) Role of human milk in extremely low birth weight infants' risk of necrotising enterocolitis or death. Journal of Perinatology;29(1):57-62

- Hill P.D et al (2001) Initiation and frequency of pumping and milk production in mothers of non-nursing preterm infants. J Hum Lact; 17(1) 9-13

- Gross S, RJ D, L B, RM T. (1980) Nutritional composition of milk produced by mothers delivering preterm. Journal of Pediatrics;96(4):641-4.

- Weber A, Loui A, Jochum F, Buhrer C, Obladen M. (2001) Breast milk from mothers of very low birthweight infants: variability in fat and protein content. Acta Paediatrica;90(7):772-5.

- Charpak N, Ruiz J.(2007) Breast milk composition in a cohort of preterm infants' mothers followed in an ambulatory programme in Colombia. Acta Paediatr ;96(12):1755.

- Lucas A, Hudson G. (1984) Preterm milk as a source of protein for low birthweight infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood;59(9):831-6.

- Jarvis C. (2010) Enteral Feeding on the Neonatal Unit. Trent Perinatal Network.

- Wang Q, Dong J, Zhu Y. (2012) Probiotic supplement reduces risk of necrotizing enterocolitis and mortality in preterm very low-birth-weight infants: an updated meta-analysis of 20 randomized, controlled trials. J Pediatr Surg; 47(1):241-8.

- AlFaleh K1, Anabrees J. (2013) Efficacy and safety of probiotics in preterm infants. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 6(1):1-9.

- Janvier A, Malo J, Barrington K. (2014) Cohort Study of Probiotics in a North American Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Ped; 164 (5); 980–985

- Hay W Jr. (2009) Optimizing protein intake in preterm infants. Journal of Perinatology; 29(7): 465–466.

- Modi .N (2006) Donor Breast Milk Banking – unregulated expansion requires evidence of benefit (letter) BMJ; 333:1133-4

- Chauhan M. et al (2008) Enteral Feeding for very low birth weight infants – reducing the risk of necrotising enterocolitis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93:F162-66

- AAP COMMITTEE ON NUTRITION, AAP SECTION ON BREASTFEEDING, AAP COMMITTEE ON FETUS AND NEWBORN. Donor Human Milk for the High-Risk Infant: Preparation, Safety, and Usage Options in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20163440

- Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Biological Hazards on a request from the commission related to the microbiological risks of infant formulae and follow on formulae.(2004) The EFSA Journal 113, 1-34

- Guidelines for making up special feeds for infants and children in hospital. (2007). Food Standards Agency.

- Bhatia J, Greer F, and the Committee on N. (2008) Use of Soy Protein-Based Formulas in Infant Feeding. Pediatrics;121(5):1062-68.

- Morley R, Fewtrell MS, A. Abbott R, Stephenson T, MacFadyen U, Lucas A.(2004) Neurodevelopment in Children Born Small for Gestational Age: A Randomized Trial of Nutrient-Enriched Versus Standard Formula and Comparison With a Reference Breastfed Group. Pediatrics;113(3):515-21.

- Embleton NE, Pang N, Cooke RJ. (2001) Postnatal Malnutrition and Growth Retardation: An Inevitable Consequence of Current Recommendations in Preterm Infants? Pediatrics;107(2):270-73.

- Clark RH, Thomas P, Peabody J. (2003) Extrauterine Growth Restriction Remains a Serious Problem in Prematurely Born Neonates. Pediatrics;111(5):986- 90.

- Wood N, Costeloe K, Gibson A, Hennessy E, Marlow N, Wilkinson A, et al.(2003) The EPICure study: growth and associated problems in children born at 25 weeks of gestational age or less. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal & Neonatal Edition ;88(6):F492-500.

- Ford GW, Doyle LW, Davis NM, Callanan C.(2000) Very low birth weight and growth into adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine;154(8):778-84

- McClure R.J., Newell S.J. (2000) Randomised controlled study of clinical outcome following trophic feeding. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 82 F29-33

- Tyson J.E. Et al (2007) Dilemmas initiating enteral feedings in high risk infants: how can they be resolved? Seminars in Perinatology;31(2):61-73

- Mosqueda E. et al (2008) The early use of minimal entral nutrition in extremely low birthweight newborns. Journal of Perinatology; 28(4):264-9

- Henderson G. et al (2009) Enteral feeding regimens and necrotising enterocolitis in preterm infants: a multicentre case-control study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed; 94: F120- 123

- Anderson D.M., and Kliegman R.M. (1991) The relationship of neonatal alimentation practices to the occurrence of endemic necrotising enterocolitis. Am J Perinatol, 8, 62-7

- Rayyis S.F. Et al (1999) Randomised trial of “slow” versus “fast” feed advancements on the incidemce of necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr,134,293-7

- Berseth C.L. Et al (2003) Prolonged small feeding volumes early in life decreases the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis in very low birht weight infants. Pediatrics, 111, 529-34

- Moody G.J. Et al (2000) Feeding tolerance in premature infants fed fortified human milk. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 30, 408-12

- Koenig W.J et al (1995) Manometrics for preterm and term infants: a new tool for old questions. Pediatrics, 95,203-206

- Patole S. et al (2003) Virtual elimination of necrotising enterocolitis for 5 years – reasons? Med Hypotheses, 61, 617-22

- Mihatsch W.A. Et al (2002) The significance of gastric residuals in the early enteral feeding advancement of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics; 109: 457-9

- Quigley M.A., et al (2007) Formula milk versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD00297

- De Ville K. et al (1998) Slow infusion feedings enhance duodenal motor responses and gastric emptying in preterm infants. Am J Clin Nutr, 68, 103-8

- Schanler R.J. (2003) Chapter 28: The Low Birth Weight Infant. In Walker, Watkins and Duggan (Eds) Nutrition in Pediatrics: Basic Science and Clinical Applications, 3rd Ed. Hamilton, Ontario, BC Decker, Inc

- Edmond K., Bahl R. (2006) Optimal Feeding of low birth weight infants – technical review. World Health Organisation.

- Sertac Arslanoglu et al (2010) Optimisation of human milk fortification for preterm infants : new concepts and recommendations. J Perinat. Med. 38; 233- 238

- Daly S.E et al (1993) Degree of breast emptying explains changes in the fat content, but not fatty acid composition of human milk. Exp Physiol;78(6) 741- 55

- Narayanan I et al (1984) Fat loss during feeding of human milk. Arch Dis Child; 59(5): 475-7

- Bertino E. et al (2009) Benefits of donor human milk for preterm infants: current evidence. Early Human Development 85 s9-s10

- Boyd C.A. Et al (2007) Donor breast milk versus formula milk for preterm infants: systematic review and meta analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed; 92: F169

- Donor Breast Milk banks: the operation of donor milk bank services. (2010) NICE Guidance CG93.

- Colaizy TT1, Carlson S, Saftlas AF, Morriss FH Jr. (2012) Growth in VLBW infants fed predominantly fortified maternal and donor human milk diets: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr; 12:124

- Polberger S.K.T et al (1990) Urinary and serum urea as indicators of protein metabolism in very low birth weight infants fed varying human milk protein intakes. Acta Paed Scand;79:737-42

- Moro GE et al(1991) Growth and Metabolic Responses in Low-Birth-Weight Infants Fed Human Milk Fortified with Human Milk Protein or with a Bovine Milk Protein Preparation. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition; 13(2):150-54.

- Hagelberg S et al.(1982) The protein tolerance of very low birth weight infants fed human milk protein enriched mother's milk. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica;71(4):597-601.

- Lucas A, Fewtrell M, Morley R, Lucas P, Baker B, Lister G, et al. Randomized outcome trial of human milk fortification and developmental outcome in preterm infants. Am J Clin Nutr 1996;64(2):142-51.

- Schanler R.J(1999) Feeding strategies for premature infants: randomized trial of gastrointestinal priming and tube-feeding method. Pediatrics;103(2):434-9

- McClure RJ, Newell SJ. (1996) Effect of fortifying breast milk on gastric emptying. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal & Neonatal Edition;74(1):F60-2.

- Ewer AK, Yu VY. Gastric emptying in pre-term infants: the effect of breast milk fortifier. Acta Paediatrica 1996;85(9):1112-5.

- Quan R, Yang C, et al (1994) The Effect of Nutritional Additives on Anti-Infective Factors in Human Milk. Clinical Pediatrics;33(6):325-28.

- Jocson MAL, Mason EO, Schanler RJ.(1997) The Effects of Nutrient Fortification and Varying Storage Conditions on Host Defense Properties of Human Milk. Pediatrics; 100(2):240-43.

- De Curtis M, Candusso M, Pieltain C, Rigo J. Effect of fortification on the osmolality of human milk.(1999) Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed.;81(2):F141-43.

- Janjindamai W, Chotsampancharoen T. (2006) Effect of fortification on the osmolality of human milk. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand.89/9: 1400- 3.

- Brown J, Embleton N, Harding J, McGuire W. (2016) Multi-nutrient fortification of human milk for preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD000343

- Arslanoglu S, Corpeleijn W, Moro G, Braegger C, Campoy C, Colomb V, et al. (2013) Donor human milk for preterm infants: current evidence and research directions. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 57(4):535-42

- Boehm G, Teichmann B, Jung K, Moro G. (1998) Postnatal development of urea synthesis capacity in preterm infants with intrauterine growth retardation. Biology of the Neonate;74(1):1-6.

- Kuschel C,Harding J. (2000). Protein supplementation of human milk for promoting growth in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD000433

- Arslanoglu S, Moro GE, Ziegler EE. Adjustable fortification of human milk fed to preterm infants: does it make a difference? Journal of Perinatology 2006;26(10):614-21.

- Embleton NE, Pang N, Cooke RJ. Post-natal malnutrition and growth retardation: an inevitable consequence of current recommendations in preterm infants? Pediatrics 2001;107:270–3.

- R W I Cooke, L Foulder-Hughes, Growth impairment in the very preterm and cognitive and motor performance at 7 years, Arch Dis Child 2003;88:482-487

- http://www.unicef.org.uk/Documents/Baby_Friendly/Research/Liz_Jones_article_full.pdf?epslanguage=en

- http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=3265

- http://www.northtrentneonatal.nhs.uk/UserFiles/File/Guidelines/Longline%202011.pdf

- Andersen C, Hart J, Vemgal P, Harrison C, Prospective evaluation of a multi-factorial prevention strategy on the impact of nosocomial infection in very-low-birthweight infants. J Hosp Infect. 2005 Oct;61(2):162-7.

- Parker LA et al. Effect of Gastric Residual evaluation on enteral intake in preterm infants JAMA Pediatrics 2019; 173 (6); pp 534-543.

Last reviewed: 14 January 2020

Next review: 01 January 2023

Author(s): Dr Claire Granger, Neonatal Grid Trainee, WoS

Co-Author(s): Other Professionals Consulted: Dr A. Powls Consultant Neonatologist, PRM; Lorraine Cairns, Paediatric Dietician RHSC; Acknowledgements: Dr J. Simpson Consultant Neonatologist, RHSC

Approved By: WoS Neonatology MCN